High Ideals and Practical Necessities

Toni P. Anderson writes an engaging new history of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers

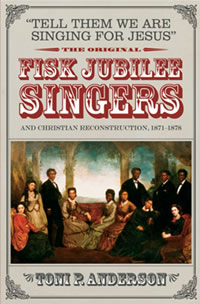

According to Toni P. Anderson’s “Tell Them We Are Singing for Jesus”: The Original Fisk Jubilee Singers and Christian Reconstruction, 1871-1878, the group that introduced the world to Negro spirituals didn’t even want to perform them. Many of the young men and women who made up the original Jubilee Singers had been born into slavery, and for them the songs were a painful reminder of bondage. Adam Spence, the pious white principal of The Fisk School, as it was then known, thought they were “letting down the tone of their enterprise” with such heartfelt music. Audiences, however, couldn’t get enough of the songs once they heard them, and the Fisk Jubilee Singers began to devote most of their program to beloved spirituals such as “Go Down Moses” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.”

The tangle over repertoire is just one instance of the tension between high ideals and practical necessity that marked the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ early years, according to Anderson, who frames her history of the chorus within the religious ideology of its parent institution. Fisk was founded in 1866 by the American Missionary Association, an abolitionist Christian organization that aided freedmen after the Civil War. Convinced that former slaves would only become responsible citizens through indoctrination in Christian values, the AMA declared its mission to “elevate, educate and evangelize an ignorant and downtrodden people.” Fisk was housed in the grim, ramshackle environment of an abandoned Union Army hospital, but it nevertheless imposed high standards of propriety and piety on its students, with the dour Spence setting the bar.

Christian righteousness didn’t pay the bills, however, and within a few years of its founding the school was on the brink of closing for lack of money. Enter George White, Fisk’s treasurer and music instructor, who was as fiery as Spence was reserved. His forceful personality “threatened Spence,” according to Anderson, and the two men bickered continually. When White proposed taking a chorus of his best singers on a fundraising concert tour, Spence objected, fearing, as he wrote at the time, that the public attention would distract the students from their studies, “dissipating their minds and lowering their piety.” White was undeterred, and in October 1871 he took the group to Ohio for their first formal engagements, naming them the “Jubilee Singers” along the way.

Christian righteousness didn’t pay the bills, however, and within a few years of its founding the school was on the brink of closing for lack of money. Enter George White, Fisk’s treasurer and music instructor, who was as fiery as Spence was reserved. His forceful personality “threatened Spence,” according to Anderson, and the two men bickered continually. When White proposed taking a chorus of his best singers on a fundraising concert tour, Spence objected, fearing, as he wrote at the time, that the public attention would distract the students from their studies, “dissipating their minds and lowering their piety.” White was undeterred, and in October 1871 he took the group to Ohio for their first formal engagements, naming them the “Jubilee Singers” along the way.

Anderson portrays the troupe’s first months as one hurdle after another—scant funds for food or appropriate winter clothing, poorly attended concerts, and a persistent tendency in the press to equate them with the popular minstrel shows, which polite society regarded as vulgar. Spence and the AMA remained unsupportive, and local ministers were often dubious about whether such entertainment belonged in their churches. Even so, writes Anderson, “White and his company held fast to the belief that their mission was divinely inspired.” Determined to succeed as musical evangelists, the singers began to set aside popular and patriotic songs in favor of the Negro spirituals that captivated their Northern audiences. Their faith yielded material benefits. The new repertoire, according to Anderson, was “a significant step forward in solidifying their musical identity and providing a marketing niche to set them apart from other choral groups.”

The crowd-pleasing program and the endorsement of prominent evangelist Henry Ward Beecher turned things around for White’s young chorus, and for the next seven years they toured the United States and Europe to tremendous acclaim. They were especially popular in England, where first-class hotels vied for the opportunity to house them, and crowds followed them through the streets. In their homeland, however, their success as performers did not exempt them from the humiliation of white racism. They were frequently turned away from restaurants and hotels in both the North and South, and railroads refused to honor their first-class tickets.

In spite of the persistent hardships, the Fisk Jubilee Singers not only rescued the school from financial ruin, but ultimately achieved White’s dream of funding the construction of its first permanent building. Jubilee Hall was dedicated on January 1, 1876, and still stands today, registered as a National Historic Landmark. The Jubilee Singers are also still thriving, though the original ensemble endured only two more years under White’s direction. The pressures of constant performance fostered conflicts within the group, which ultimately became so demoralized that White resigned, and his chorus was disbanded. (A reorganized version of the Jubilee Singers began touring the following year.)

In spite of the persistent hardships, the Fisk Jubilee Singers not only rescued the school from financial ruin, but ultimately achieved White’s dream of funding the construction of its first permanent building. Jubilee Hall was dedicated on January 1, 1876, and still stands today, registered as a National Historic Landmark. The Jubilee Singers are also still thriving, though the original ensemble endured only two more years under White’s direction. The pressures of constant performance fostered conflicts within the group, which ultimately became so demoralized that White resigned, and his chorus was disbanded. (A reorganized version of the Jubilee Singers began touring the following year.)

Any collective artistic enterprise is bound to be rife with personal conflicts, and one of the strengths of Anderson’s book is its vivid portrait of the zealous and temperamental personalities among and around the Fisk singers. She writes about the Spence/White tussles and the ego battles within the chorus in an intimate, almost gossipy tone, with generous quotes from the letters and recollections of the participants. In fact, she makes lively use of primary sources throughout the book, including reviews from the U.S. and Europe, documents from the AMA, and a great many letters. Anderson is chair of the music department at LaGrange College, and she provides a brief, excellent overview of the origins of the traditional Negro spiritual, and how the Jubilee Singers both preserved and changed it. She also delineates the 19th century debate—so alien to postmodern sensibilities—over whether the spirituals had “artistic merit.”

“Tell Them We Are Singing for Jesus” provides a splendid history of the first Jubilee Singers and is necessary reading for anyone interested in the early years of Fisk University. Beyond that, Anderson’s skillful reading of the social, religious, and artistic forces that shaped the chorus makes her book a vivid snapshot of the era.