God’s Will

A new book considers the legacy of Will Campbell, writer, minister, and activist

To consider at length the witness of Will Campbell is to imagine an alternative present in which the civil-rights movement is fused with the country-music industry, and the popular division between religion and politics no longer exists. As a songwriter, novelist, minister, and tireless advocate for incarcerated, marginalized, and hard-to-know-what-to-do-with people, Campbell defies every category. The polarities we see today had no home in him.

A close associate of Martin Luther King Jr., Kris Kristofferson, and Walker Percy, he represents the omnipartisan path not taken—he was a prophetic voice in Tennessee which slipped through the cracks of the conflicting interests of market, church, and state. When Will Campbell died in 2013 at age eighty-eight, the news made the front page of The New York Times. But by then the Nashville man once described as the “Aquinas of the Rednecks” was no longer on the radar of most people who live in Nashville.

A close associate of Martin Luther King Jr., Kris Kristofferson, and Walker Percy, he represents the omnipartisan path not taken—he was a prophetic voice in Tennessee which slipped through the cracks of the conflicting interests of market, church, and state. When Will Campbell died in 2013 at age eighty-eight, the news made the front page of The New York Times. But by then the Nashville man once described as the “Aquinas of the Rednecks” was no longer on the radar of most people who live in Nashville.

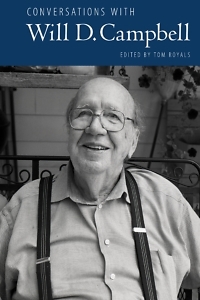

As Conversations with Will D. Campbell, a new book edited by Tom Royals, demonstrates, this is a tragic oversight. Will Campbell spoke with precision, humor, and deep compassion to the catastrophes and contradictions that drive our news cycles now more than ever. As one who accompanied students passing through angry mobs in an effort to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, counseled and supported Freedom Riders in the sixties, ministered to imprisoned Klansmen in the seventies, and traveled with Waylon Jennings as a cook in the eighties, Campbell was a great witness. His love of God and country was characterized by deep realism, hope, and lament: “I pay taxes. But I don’t celebrate it,” he remarked in 1984. “I repent of it. So on the Fourth of July I ring the bells … not in celebration, but in lamentation for the shameful history of this country in which I live and prosper.”

Campbell remains one of our most formidable critics of nationalism: “Once you start saying, ‘God made this country great,’ then you can justify anything under the sun, including blowing people’s sweetbreads right through their earholes,” he said. For Campbell, the needful corrective to such madness is the Beloved Community, a living alternative to the established evil of institutions. Church, in Campbell’s thought, is an endlessly active verb that conjures community every which way.

Conversations with Will D. Campbell offers us a glimpse into the ways he saw his writing (including his acclaimed memoir Brother to a Dragonfly) as an extension of his own vocation toward community, the long work of levelling with self and others: “I discovered long ago that the only way we learn from one another is by being willing to bare as much about ourselves as our nervous systems will let us, which is never very much,” he said. “Consequentially, we don’t learn much from each other.”

Campbell’s insight concerning the imperative to say what you see, stick to it, and let the chips fall—we come to find out—was hard won. He regretted his quiet and obedient departure from the position of chaplain at the University of Mississippi when administrators complained of his activism. When James Lawson faced expulsion from the Vanderbilt Divinity School after his arrest during the Nashville lunch-counter sit-ins, he was initially inclined to follow the advice of Dean Robert Nelson and withdraw quietly to avoid making trouble. Campbell spied a longer game: “You don’t let them off the hook,” he advised. “You’re going to have to leave, Jim, but make them kick you out so that they and the world will know … where this institution stands and what it’s up to.” Following Campbell’s advice, Lawson did force Vanderbilt’s hand. The rest is history.

Campbell’s insight concerning the imperative to say what you see, stick to it, and let the chips fall—we come to find out—was hard won. He regretted his quiet and obedient departure from the position of chaplain at the University of Mississippi when administrators complained of his activism. When James Lawson faced expulsion from the Vanderbilt Divinity School after his arrest during the Nashville lunch-counter sit-ins, he was initially inclined to follow the advice of Dean Robert Nelson and withdraw quietly to avoid making trouble. Campbell spied a longer game: “You don’t let them off the hook,” he advised. “You’re going to have to leave, Jim, but make them kick you out so that they and the world will know … where this institution stands and what it’s up to.” Following Campbell’s advice, Lawson did force Vanderbilt’s hand. The rest is history.

As Campbell saw it, these clarifying exchanges between the movement of communal spirit and the static stubbornness of institutions is where righteous breakthroughs occur. In one interview, he recounted Diane Nash’s confrontation with Mayor Ben West on the steps of Nashville’s City Hall. West avoided a direct answer when Nash asked if he believed a segregated lunch counter was right. “Do you think it is Christian?” she persisted. “No, I don’t,” he finally conceded.

Campbell viewed this moment as a decisive blow to dysfunction and an invitation to access a longed-for integrity common to everyone. The question of what is and isn’t passably “Christian” can feel, at first blush, reminiscent of a bygone era. But it is a question worth considering when political figures win elections with ads that draw on white-nationalist rhetoric while claiming affiliation with area churches—and when those churches offer no clarifying word on where their mission and that of their politically powerful members coincide or don’t.

This is where Will Campbell’s witness remains peculiarly needful. He worried about belief (or professed belief) without embodiment—of Christ without Jesus. “What troubles me is what an emphasis on belief does to discipleship. It negates discipleship, really,” he said. “Once I make what I believe the issue, then I’m off the hook.”

For Campbell, the “hook” was always the work of real love for real people in the everyday details. Faith without details is dead. When monied interests and the elected officials who serve them appear to be on the run from every form of specificity, Campbell’s insistent grace is more welcome than ever.

David Dark is the author of Life’s Too Short To Pretend You’re Not Religious, The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, Everyday Apocalypse, and The Gospel According To America. He lives in Nashville and teaches at the Tennessee Prison for Women and Belmont University.

David Dark is the author of Life’s Too Short To Pretend You’re Not Religious, The Sacredness of Questioning Everything, Everyday Apocalypse, and The Gospel According To America. He lives in Nashville and teaches at the Tennessee Prison for Women and Belmont University.