Holy War, Popular War

In a comprehensive history of the First Crusade, Jay Rubenstein weighs in on Apocalyptic fever, the advent of chivalric warfare, and the power of popular religion

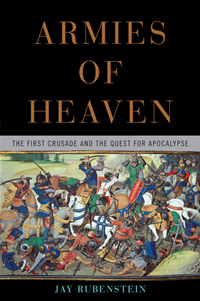

Of all the sayings about history––it’s one damned thing after another; it’s written by the winners, it’s doomed to repeat itself––none is more incriminating than the one attributed to Lenin: A lie repeated often enough becomes the truth. Knoxville historian Jay Rubenstein takes this phenomenon into account in Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse. Rejecting common narratives about the First Crusade (which took place between 1096 and 1099), Rubenstein digs deep, giving as much weight to the experiences of soldiers and peasants as to those of lords and ranking clerics. The result is a three-dimensional, highly readable account of a daring and barbaric mission as familiar to modern readers as it was to ancient ones: the attempt to reclaim the Holy Land and initiate Christ’s return.

Rubenstein begins his tale with the buildup to crusade. Jerusalem, having fallen in 638, was in Muslim hands. In 1095 Pope Urban II, one of two men claiming to be pope at the time, preached a sermon advocating a mission to liberate the city and restore Christian rights to pray at the Holy Sepulchre, Christ’s tomb. Simultaneously, a street prophet and spiritual grifter named Peter the Hermit brought the same message to the masses, inspiring thousands of Germans and Frenchmen to take up the cause. In the East, Roman Emperor Alexius I Comnenus, who had lost ground to Turkish Muslims, welcomed the mission. What he expected was a well-trained garrison of Frankish mercenaries to shore up his legions. What he got was something entirely different.

Estimates vary, but the masses who took up the cross in 1096 and marched east were numbered at around 100,000. Initially, there were two distinct crusades: a militarized version led by bishops, lords, and knights; and a popular crusade made up of unarmed commoners, illiterate clerics, and holy fools. It got ugly early. Before leaving Europe, the combined forces slaughtered thousands of Jews, who along with Muslims, pagans, and Eastern Christians were seen as enemies of true Christendom. The armies then attacked Nicea, Antioch, and other formerly Christian sites, heading deeper and deeper into the unfamiliar, treacherous Syrian desert.

Estimates vary, but the masses who took up the cross in 1096 and marched east were numbered at around 100,000. Initially, there were two distinct crusades: a militarized version led by bishops, lords, and knights; and a popular crusade made up of unarmed commoners, illiterate clerics, and holy fools. It got ugly early. Before leaving Europe, the combined forces slaughtered thousands of Jews, who along with Muslims, pagans, and Eastern Christians were seen as enemies of true Christendom. The armies then attacked Nicea, Antioch, and other formerly Christian sites, heading deeper and deeper into the unfamiliar, treacherous Syrian desert.

As losses mounted and barbarism reached unimaginable levels, the two crusades became one. Strangers in a very strange land, the Christian armies both high and low became increasingly dependent on miraculous signs, apocalyptic visions, and powerful relics. United by a fevered belief that the time of Antichrist was near––and that they themselves were helping to bring the end times about––the crusaders, operating with one foot in this world and one in the next, marched on Jerusalem. The resulting massacre is, literally, the stuff of legend.

What distinguishes Rubenstein’s work from other accounts is the significance he grants to the more otherworldly aspects of the campaign. In the field of religious studies, such phenomena come under the rubric of “popular religion”—extra-ecclesial matters like crying statues, stigmata, visions, and miraculous healings. Rubenstein, a professor of medieval history at the University of Tennessee, doesn’t refer to popular religion per se, but his description of the popular crusade is consistent with the concept. He notes that its leaders included “two priests, one lapsed monk, and one fanatical layman. They believed themselves divinely appointed, and one of them even had a letter from heaven to prove it.”

As the group wandered farther from their physical home, they also strayed from their spiritual and political homes––that is, the doctrinal system of the Roman Catholic Church and the feudal organization of the Frankish kingdom. Organization broke down, and more inscrutable forces held sway. In this way, illiterate peasants like Peter Bartholomew were granted key roles alongside the crusade’s more regal members, such as Count Raymond of Saint-Gilles and Godfrey of Bouillon. Peter’s miraculous discovery of the so-called “Holy Lance”––the spear that, in John’s account of the crucifixion, pierced Jesus’s side––ratcheted the crusaders to an even more fevered pitch.

As the group wandered farther from their physical home, they also strayed from their spiritual and political homes––that is, the doctrinal system of the Roman Catholic Church and the feudal organization of the Frankish kingdom. Organization broke down, and more inscrutable forces held sway. In this way, illiterate peasants like Peter Bartholomew were granted key roles alongside the crusade’s more regal members, such as Count Raymond of Saint-Gilles and Godfrey of Bouillon. Peter’s miraculous discovery of the so-called “Holy Lance”––the spear that, in John’s account of the crucifixion, pierced Jesus’s side––ratcheted the crusaders to an even more fevered pitch.

While the crusaders became increasingly loosed from their spiritual moorings, so too did they abandon their moral ones. The terrors unleashed on Muslims, as well as Jews, Eastern Christians, and practically anything else in the army’s path, were unprecedented. It was, according to Rubenstein, an entirely new form of warfare: holy war. “Since the time of Constantine the Great, Christian knights, kings, and emperors had always fought with God in mind,” Rubenstein writes. “For these two reasons the crusade was new: It offered warriors a way to save their souls through combat, and it was a new type of war––complete with its own set of rules and its own moral code.”

Rubenstein tells his tale with great imagination and thorough research. Armies of Heaven cites the work of Eastern and Western scholars, both contemporary and ancient. An academic book, Armies of Heaven is thoroughly engaging anyway; its straightforward prose and occasional flashes of dark humor are accessible to even casual historians.

If history is made up of well-repeated lies, what’s the point of recounting the fevered visions and apocalyptic dreams of a violent hoard of Christian marauders? According to Rubenstein, those very dreams, more than promises of wealth and glory, drove the crusaders to remarkable feats of both bravery and cruelty. The crusade they began, however misguidedly, changed the face of Europe and forged Western and Eastern identities that remain in place today. Their dreams also offer a warning: “The rivers of blood such a war unleashes run no less deep,” writes Rubenstein, “specious though their otherworldly justifications may be.”