Illuminating the Invisible Work

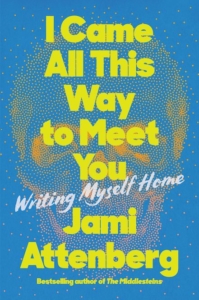

Jami Attenberg reveals the writing life

Think of the word “contain.” Consider how it means two things: to hold, as well as to hold back. This is what we’re talking about when we talk about great personal essays, how they express the inexpressible, how they take us inside the writer’s life and, in usually fewer than 20 pages, return us to a piece of ourselves. This is what Jami Attenberg does in her 2022 memoir-in-essays, I Came All This Way to Meet You: Writing Myself Home. Here, the bestselling novelist cracks open the image of a successful writer to reveal what it requires and what’s happened along her way.

“For a long time,” Attenberg begins, “I worked day jobs that were different from the one I have now. For 20 years, I hustled.” The ensuing list of what she did for money during those decades — and her tone in the recounting — introduce us to the voice of a hard-working woman in possession of humor and grit (“I have been harassed at work, but seriously, who hasn’t?”). She realized she could no longer go on as she had, serving other people’s ideas. Eventually, she thought, “What about my ideas? When do I own them?” And so, she set out to operate in service to her own ideas. She wrote her first book. “Everything got easier, in a way, once I realized this was what I wanted,” she writes, “even as things got much, much harder.”

One of the particular and rich gifts of these essays is Attenberg’s candor. Another is her magnanimity. I will go one step further and add that it’s not only her honesty that’s valuable, but the fact that she possesses perspective. Attenberg, now 51 years old, may be best known for her fourth novel, The Middlesteins (2012). It’s set in the Chicago suburbs, where she grew up. “For that was how long I needed to be away from it to consider that place: 20 years,” she reflects on writing it. “Why did this work? I believe that one must arrive at an intersection of hunger and fear to make great art.” From the outside, writers who have broken through to success rarely appear hungry. Or, rather, they become known for having “made it” instead of all the toiling it took. Let’s define success in this context by two criteria: the freedom to write what one chooses (to serve one’s own ideas), as well as earning a living at it.

Attenberg is a champion of other writers. Since 2018, she’s spearheaded the 1,000 Words of Summer project, an annual online group of people who write 1,000 words a day for two weeks. There are now more than 15,000 participants. Every day, Attenberg sends them a letter of encouragement. This book includes inspiration and solace drawn from the same spirit. “When I write, it’s a place I can go to feel safe,” she says. Many authors are not as generous about helping others or even opening up about their own process.

An unorthodox component of I Came All This Way to Meet You is its organization. There’s no index. These 17 essays are not structured chronologically, although they are clustered into three parts: “The Long and Winding Road,” “Brief and Dire Spasms of Turbulence,” and “A Landing, of a Kind.” She explores, by turns, moving from her Brooklyn apartment to New Orleans (“I did not want to grow old in New York. I had been young there, and that was enough.”); her father’s career as a traveling salesman (“If you can sell one thing,” he says, “you can sell anything.”); the sexual assault she endured at age 17 and its repercussions (“It shaped me in so many ways. Who knows who I would have become otherwise. I would have been a writer regardless, but I can’t help but feel that part of my drive comes from anger.”).

She writes about traveling, touring, sleeping in 26 beds over one seven-month period, reckoning with having a hysterectomy, wearing a bikini for the first time at 45, the time she got booed at a reading, what she learned from Olive Kitteridge, and other subjects. Essentially, she mines her life, offering up the glimmers. About a class of her creative writing students, she writes, “They just wanted to know: Were they good enough? I didn’t tell them that I feared at every moment that this new kind of freedom would be taken away from me, that at any moment any of our freedom could be gone. And how do you explain that nearly no one is good enough, it has to do with how much work you put in, your diligence, your persistence, some fortune, some luck.”

She writes about traveling, touring, sleeping in 26 beds over one seven-month period, reckoning with having a hysterectomy, wearing a bikini for the first time at 45, the time she got booed at a reading, what she learned from Olive Kitteridge, and other subjects. Essentially, she mines her life, offering up the glimmers. About a class of her creative writing students, she writes, “They just wanted to know: Were they good enough? I didn’t tell them that I feared at every moment that this new kind of freedom would be taken away from me, that at any moment any of our freedom could be gone. And how do you explain that nearly no one is good enough, it has to do with how much work you put in, your diligence, your persistence, some fortune, some luck.”

In this book, Attenberg achieves something that Patricia Hampl described Alfred Kazin having done with A Walker in the City (1951): “What Kazin was able to do — what every memoirist can attempt — in liberating himself from the demands of show-don’t-tell narrative was enter into reflection, into speculation, into interpretation, and to use the fragment, the image, the vignette, rather than narratively linked scenes, to form his world and his book. He was able to show and tell.” Boom!

Attenberg’s voice makes for great company: wry, sensitive, genuine, both confident and humble, curious and wise. Like the most interesting journeys, hers has not been linear. This book is most notable for the ways in which it illuminates all of the invisible work that goes into a writing life, the stories from behind the scenes, the truths rooted in her fiction, her showing and her telling.

Sarah Norris has written about books and culture for The New Yorker, San Francisco Chronicle, The Village Voice, and others. After many years away, she’s back in her hometown of Nashville.