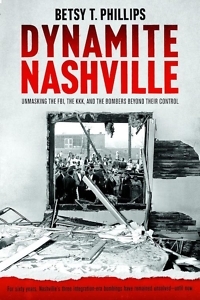

John Kasper, Ezra Pound’s Biggest Fan

Book Excerpt: Dynamite Nashville: Unmasking the FBI, the KKK, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control

John Kasper has long been most people’s main suspect in the Nashville bombings, since the bombings started after he arrived in Nashville in 1957 and they concluded after he got tired of going to prison for being a racist activist in the early ’60s. The problem with Kasper as a suspect is that while he could rile a crowd, he wasn’t very good at actually committing terrorist acts. The plots we know he headed up fizzled out.

Also, a lot of other racists loathed him. If our bombings could have feasibly been pinned on him, it’s very likely that some other racist, possibly even Emmett Carr, Grand Titan of Middle Tennessee for the U.S. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, would have told the world that Kasper did it. Still, it’s also obvious that Kasper was an important part of the mix that led to Nashville’s bombings; Kasper wasn’t the mastermind behind our bombings, but it’s unlikely our bombings would have happened without him.

Kasper was born in 1929 in Camden, New Jersey. His parents were very conservative Protestants, and by the time Kasper came to Nashville, his mother was attending a Bible Presbyterian Church in New Jersey, the same small sect Nashville’s Rev. Fred Stroud belonged to. As Kasper put it in a letter to his mentor, poet Ezra Pound, “Now der Gasp wuz borned at Camden, New Jersey and brung up in Pennsauken, N.J. Ma is a renegade Catholic, Pa was a Lutheran, and we wuz members of the 1st Presbyterian Church of Merchantville.” Call it a fake patois, call it baby talk, whatever this way of writing was, it certainly illustrates the strange relationship that developed over the years between Pound and Kasper.

Kasper attended Columbia University, which was where he became a fan of Pound’s and began corresponding with him. At Pound’s request, Kasper started a small publishing company in 1951 — Square Dollar Press — which published Pound. During his time in New York City, Kasper also ran a bookshop in Greenwich Village. At this point, Kasper was already a raging anti-Semite, but he was also holding integrated dance parties at the shop, dating a Black woman, and, according to the FBI, sometimes sleeping with a Black man.

Kasper’s anti-Black attitudes seemed to more fully form once he moved to Washington, D.C., to be closer to Ezra Pound, who was imprisoned at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in the city on charges of treason for his fascist activities during World War II. Pound and Kasper corresponded extensively. Luckily for Pound defenders, Kasper destroyed the letters he received from the poet, so we don’t know what kinds of direction and encouragement Pound was giving Kasper. The letters Pound kept from Kasper, though, make it clear that Kasper was keeping Pound up to date on his activities and that Kasper felt his activities would please Pound.

Kasper’s anti-Black attitudes seemed to more fully form once he moved to Washington, D.C., to be closer to Ezra Pound, who was imprisoned at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in the city on charges of treason for his fascist activities during World War II. Pound and Kasper corresponded extensively. Luckily for Pound defenders, Kasper destroyed the letters he received from the poet, so we don’t know what kinds of direction and encouragement Pound was giving Kasper. The letters Pound kept from Kasper, though, make it clear that Kasper was keeping Pound up to date on his activities and that Kasper felt his activities would please Pound.

I think — and this is peak nerdy — that Pound has benefited from so few scholars looking at him and Donald Davidson together. As long as Pound defenders can say, “Come on! How could a brilliant poet be a dangerous and virulent racist providing support and inspiration to racial terrorists? Point to one other example!” there’s always doubt.

But what we in Nashville know, or should now know, is that there was one other very prominent example: Donald Davidson. And if a deeply beloved, well-regarded professor at the city’s elite university could do this, why couldn’t a guy hiding from treason charges in a hospital room do the same?

Oddly enough, considering all they had in common, Davidson and Kasper didn’t work together much. Pound scholar and Kasper biographer Alec Marsh writes, “Davidson was an ideologue whose vocation as a poet, agrarian philosopher, Jeffersonian principles, and Southern orientation overlapped Pound’s in several ways, and might have been a natural ally, even a moderating influence on Kasper.” Kasper may have been a dynamic, charismatic, persuasive white supremacist who was out in the streets calling for violence, but he was a carpetbagger, and it’s not surprising that Davidson — and Carr — wanted little part of him.

In direct response to Brown v. Board of Education, Kasper founded the Seaboard White Citizens Council in the Washington, D.C., area. This put him fully on the FBI’s radar, and they were tracking him as his little band of racists burned crosses and picketed the White House. Kasper was also a leader in the Tennessee White Citizens Council, though, since Nashville already had Davidson and company, Tennessee wasn’t desperate for another group of ostensibly “decent” racists, especially because Kasper was so openly aligned with the Klan — at least at first.

[Read an interview with Betsy Phillips here.]

Excerpted from Dynamite Nashville: Unmasking the FBI, the KKK, and the Bombers Beyond Their Control by Betsy Phillips, forthcoming from Third Man Books in July 2024. Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. Betsy Phillips writes about history and politics for the Nashville Scene.