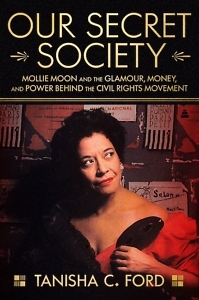

Lavish Nights and Civil Rights

Tanisha Ford uncovers the tale of Mollie Moon, powerhouse fundraiser for racial justice

Every year, the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change at the University of Memphis bestows an award for a nonfiction book that best furthers understanding of the American Civil Rights Movement and its legacy. This year’s winner is Tanisha Ford’s Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, and Power Behind the Civil Rights Movement, an engrossing story of a Black socialite who raised the funds that fueled grassroots struggles for racial justice.

Tanisha Ford is a professor of history at the CUNY Graduate Center. Her previous books include the award-winning Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul, as well as Dressed in Dreams: A Black Girl’s Love Letter to the Power of Fashion and Kwame Brathwaite: Black is Beautiful. Her writing has appeared in publications such as The Atlantic, New York Times, Time, Elle, and Harper’s Bazaar. Our Secret Society has won an NAACP Image Award and was on “best books” lists for Vanity Fair and Ms. Magazine.

Ford answered questions from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Your subject, Mollie Moon, is probably best known as the founder and longtime hostess of New York City’s high-society Beaux Arts Ball. Why was this role more significant than we might assume?

Tanisha Ford: Mollie Moon was a force. Born in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, in 1907, she was educated at Meharry Medical School, where she earned a degree in pharmacy before becoming a social worker. She moved to New York City around 1930. In New York, she became known as a major fundraiser. The Beaux Arts Ball was her signature event.

As I started to learn more about Mollie Moon’s life and her career, I realized that the fundraising piece was far more significant to the history of the Civil Rights Movement than we have previously recognized. Sit-ins, marches, freedom rides, breakfast programs for schoolchildren — all of those things require money. Where does that money come from? Well, Mollie Moon was one of the people working behind the scenes to raise money for the movement. Once I realized that she wasn’t just this high-society maven — that she was actually a fundraiser — her biography started to click into place. Her story is about the real cost of racial justice.

Chapter 16: In the civil rights era, the National Urban League seemed like an “establishment” organization connected to politicians, foundations, and corporations. But in the 1930s, Moon operated in the more radical circles of the left. How did she reconcile her progressive politics with her elite standing?

Ford: Moon’s leftist leanings emerged in the early 1930s. By this point, she had graduated from Meharry, married and divorced her first husband, and moved from the Deep South to Harlem, where a large-scale movement for racial justice was unfolding. We have given this movement a variety of names, such as the New Negro Movement, the Harlem Renaissance, or Black internationalism. Moon developed deep ties to a community of thinkers, writers, activists, and artists. She traveled with a group of people — including her future husband Henry Lee Moon, Louise Thompson (Patterson), Langston Hughes, and Dorothy West — to Moscow, in 1932, to make a film about the horrors of Jim Crow segregation and labor exploitation in the United States. There she became more deeply radicalized, considering herself something of a Black communist. She grew deeply concerned with working-class and working-poor women’s issues. After living briefly in Berlin, she returned to the U.S. and connected with members of the white and Black left in New York.

Moon got into the work of fundraising by chance. She was trying to protect the Harlem Community Art Center, which had been started by several prominent artists, including Augusta Savage, Romare Bearden, Selma Burke, and Aaron Douglas. As she displayed a talent for raising money, she was tapped by Lester Granger, the new head of the National Urban League, to launch a group that would become the fundraising arm of the National Urban League. She named it the National Urban League Guild.

Moon’s transition into this new role wasn’t seamless. In some instances, it was very fraught, as she tried to maintain her focus on Black folks on the margins. The situation became more tenuous, of course, as she increasingly became the face of the Urban League, and as the Urban League began to align itself with wealthy white billionaires. By then, Mollie’s radical bona fides were called into question by a burgeoning group of younger Black radical activists.

Chapter 16: If one were to read an obituary of Mollie Moon, she would seem like an entirely respectable civic leader. But in her heyday, her reputation was more controversial. Why is this important?

Ford: As historians, as writers, as researchers, we tend to place leading civil rights figures in a very respectable box. Respectability has become a common paradigm through which to think about people who are middle class, who are educated. It becomes, in certain ways, a shorthand “bourgeois.” Such labels can flatten out other important elements of their biographies. We either make them more respectable than they actually were to prove a point about the intersection of race, class, and gender. Or we dismiss so-called respectable folks altogether in favor of studying (often in very romantic ways) working- class people. And I get the need to study poor and working-class Black folks. But it doesn’t have to be an either/or. The reality is that people are messy. Their politics are messy. Politics don’t live neatly on a fleshy body. I really try to break Mollie Moon out of that “respectable” bubble and the concomitant class politics and behaviors we assume come with it. Despite their levels of education, despite their class status, Moon and her associates had far more complex lives.

Ford: As historians, as writers, as researchers, we tend to place leading civil rights figures in a very respectable box. Respectability has become a common paradigm through which to think about people who are middle class, who are educated. It becomes, in certain ways, a shorthand “bourgeois.” Such labels can flatten out other important elements of their biographies. We either make them more respectable than they actually were to prove a point about the intersection of race, class, and gender. Or we dismiss so-called respectable folks altogether in favor of studying (often in very romantic ways) working- class people. And I get the need to study poor and working-class Black folks. But it doesn’t have to be an either/or. The reality is that people are messy. Their politics are messy. Politics don’t live neatly on a fleshy body. I really try to break Mollie Moon out of that “respectable” bubble and the concomitant class politics and behaviors we assume come with it. Despite their levels of education, despite their class status, Moon and her associates had far more complex lives.

Chapter 16: Why did Moon’s influence within the Urban League ultimately decline?

Ford: There were many factors that led to this decline. One was a change in leadership. For 20 years, Lester Granger was at the helm of the National Urban League. He and Mollie Moon had a wonderful working relationship. They were good friends. They were both social workers, so they were also colleagues. Lester had very progressive gender politics, particularly for the era. When he was forced to retire upon reaching his 20-year term limit, a younger man, Whitney Young, was named leader of the organization. And Young had a different idea about how the Urban League should be run. He also viewed people from the Granger era as holdovers from an earlier epoch. Young wanted to bring in his own staff, his own team, who could carry out his vision. Mollie Moon, because she was aligned with Granger, was viewed as something of a relic.

Yet a number of Black women refused to accept Mollie’s diminished role. Even though the male leadership of the National Urban League preferred her to recede to the margins of the organization, Black women journalists and organizers said, “Not so fast, not on our watch. You will honor this woman who has served this organization, tirelessly, for decades and without being paid, on a strictly voluntary basis. You will honor her contributions to this organization.” For me, as a historian, that was an important part of the story to tell. It was Black women who insisted that Mollie Moon be treated with dignity.

Chapter 16: “Writing Black women’s biography,” you state, “means naming and confronting the violence of the archive.” Can you explain this idea? How did it shape your writing of Our Secret Society?

Ford: To put it plainly, archives were never spaces that were meant to hold the stories of people of African descent. The Western archival system is an extension of the European colonial project — the same colonial system that brutalized, murdered, raped, and enslaved our ancestors. We, historically, have showed up in the archive in death and infirmary records, chattel property papers, and purchase orders. We were never meant to be the central figures in archival documents or in Western histories. Many of these archives still uphold colonial archival practices.

To uncover the lives of Black women, and to tell those lives fully and as completely as possible with the materials at our disposal, means learning to read the archive against the grain. It involves using innovative methods for reading sources. As a student and a practitioner of Black women’s history, I’m always thinking about how to get at the core of the story I’m trying to tell, as it relates to Black women. With Our Secret Society, I’m using those “against the grain” methods of the Black women’s historian. I’m also using the methods of a material culturalist to look beyond the documents, to examine objects, to see what kinds of stories the objects can tell me about a life like Mollie Moon’s. I really had to use everything at my disposal to excavate Mollie Moon’s story from the archive and tell it in a way that would be historically accurate, but also methodologically innovative, and, hopefully, engagingly written.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.