Leaving the Whole World Blind

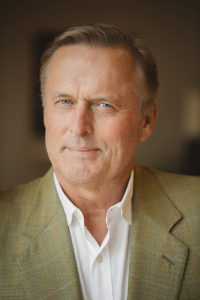

Death-penalty opponent Margaret Vandiver talks with Chapter 16 about the future of capital punishment in the Volunteer State

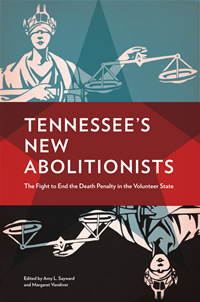

Tennessee’s New Abolitionists, edited by Amy L. Sayward and Margaret Vandiver, documents efforts to halt capital punishment in Tennessee. Contributors to the collection—including lawyers, academics, activists, a former state Supreme Court justice, death row inmates, and those whose lives have been affected by capital crimes—decry the myth of retributive justice, discuss the state’s ambivalent relationship with the death penalty, and comment on the hardscrabble organizational tactics employed by Tennessee abolitionists. In an email interview with Chapter 16, Vandiver, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Memphis, weighs in on the future of capital punishment in the Volunteer State and what its opponents can expect from Governor-elect Bill Haslam, whose administration will almost certainly skew in favor of the death penalty.

Chapter 16: How did you become interested in the death-penalty issue?

Vandiver: I grew up in Gainesville, Florida, which is located about thirty miles from death row. Florida’s legislature was the first to reinstate capital punishment. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned all capital statutes in 1972 [but the] statute was upheld in 1976, and Florida moved aggressively to resume executions. So the death penalty was the focus of a great deal of attention in the area. I became involved in the issue in the late 1970s. My interest led me to go to graduate school at Florida State University, where I studied criminology and criminal justice with a focus on capital punishment, especially its use in Florida.

Chapter 16: For those who haven’t read Tennessee’s New Abolitionists, can you describe how Tennessee’s ambivalence surrounding the death penalty is unique among the Southern states?

Vandiver: If you look at the number of executions historically in the state, and the extreme overrepresentation of African Americans among those executed, Tennessee looks much like other Southern states. But abolitionist sentiment is deeply rooted here, going back to the early governors of the state, who tried to abolish capital punishment before the Civil War. Between 1915 and 1919, Tennessee abolished capital punishment for homicide (except murders committed by prisoners), while retaining it for rape. Although abolition was partial and short-lived, no other formerly Confederate state has legislatively ended the death penalty to this day. In the 1950s and 1960s there was strong support for abolition among legislators, and capital punishment was nearly abolished again in 1965. Tennessee went forty years without an execution and has carried out only six executions in the thirty-three years its current death-penalty law has been in force.

Vandiver: If you look at the number of executions historically in the state, and the extreme overrepresentation of African Americans among those executed, Tennessee looks much like other Southern states. But abolitionist sentiment is deeply rooted here, going back to the early governors of the state, who tried to abolish capital punishment before the Civil War. Between 1915 and 1919, Tennessee abolished capital punishment for homicide (except murders committed by prisoners), while retaining it for rape. Although abolition was partial and short-lived, no other formerly Confederate state has legislatively ended the death penalty to this day. In the 1950s and 1960s there was strong support for abolition among legislators, and capital punishment was nearly abolished again in 1965. Tennessee went forty years without an execution and has carried out only six executions in the thirty-three years its current death-penalty law has been in force.

Chapter 16: In spite of the many setbacks experienced by Tennessee’s death-penalty opponents, do you think the eventual abolition of the death penalty is inevitable?

Vandiver: I hesitate to say that anything is inevitable because there are simply too many factors involved to be able to confidently predict outcomes. But I think it is likely that Tennessee ultimately will join the fifteen American states and the two-thirds of countries in the world that are getting along just fine without the death penalty. Most people don’t realize that in the U.S. since 1977, about one-fifth of one percent of homicides have resulted in an execution. And yet we devote a grossly disproportionate amount of time and money and resources and attention to that tiny fraction of cases. Getting rid of the death penalty just means treating those few homicide cases the way we already treat more than ninety-nine percent of cases. It’s a simple change and would be highly beneficial in terms of conserving resources. On the other hand, it is a mistake to underestimate the symbolic power of capital punishment. Since the 1970s, support for capital punishment has been a kind of litmus test of “toughness” for politicians, and it is difficult for legislators and governors to back away from that.

Chapter 16: In Tennessee, the abolition movement is long on passion but seems to struggle when it comes to organizing. Take, for example, the incessant renaming of its principal agency: from TADP (Tennesseans Against the Death Penalty) to DPRP to TCASK, then back to TADP. From an organizational standpoint, what does the abolition movement lack?

Vandiver: This is a good question. The abolitionist movement draws a diverse group of activists who approach the issue from widely different viewpoints. Some see abolition as consistent with a universal ethic of the sacredness of life; some approach abolition principally as a civil-rights issue; some are motivated by distress at the high level of error and inconsistency in the criminal justice system; some view capital punishment as a wasteful and inefficient government program; some believe that taking the life of a prisoner is a fundamental violation of human rights. But few people from any of these perspectives are directly and immediately affected by capital punishment, and most of them are involved in working on multiple issues. The death penalty draws a lot of attention at certain times and this attention is often focused on particular cases, but the number of activists who devote themselves entirely or primarily to this issue and who continue to work on it steadily is very small. This makes it difficult to sustain a high level of organization over time and makes fundraising particularly challenging. I think that the current abolitionist organization, Tennesseans for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, is the best organized and most effective we have had in the state. Under Rev. Stacy Rector’s direction, TADP has become a professional organization consistently doing high quality advocacy and educational work.

Chapter 16: What is the biggest barrier to death-penalty abolition in Tennessee?

Vandiver: Probably a lack of public understanding as to how the system actually functions. The death penalty in theory is very different from the death penalty in practice. If people knew what it costs to maintain a death-sentencing system; that fundamental errors, including wrongful convictions, are often not corrected even by decades of appeals; that the death penalty exacts a terrible emotional price from many correctional and criminal-justice personnel; that it continues to be imposed unequally based on race and location; that many victims’ families are opposed to capital punishment; that most of the countries of the world have abolished it; and that condemned prisoners present no greater threat in prison than other inmates, they would probably start asking why we are paying such a high price in order to continue such a flawed policy.

Chapter 16: Is it a coincidence that your book-signing at Davis-Kidd coincides with newly elected Tennessee governor Bill Haslam’s first day in office?

Vandiver: It is a coincidence! By the way, the date also overlaps with the annual meeting of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty.

Chapter 16: Governor-elect Haslam is on record as supporting the death penalty. Though he’s been mum on the issue since being elected, Haslam did recently appoint Memphis prosecutor Bill Gibbons, a vocal supporter of the death penalty, as Public Safety Commissioner. Do you think the appointment indicates tough sledding ahead for the abolition movement?

Vandiver: While the Public Safety Commissioner is in a position to influence public opinion on capital punishment, it is judges who are going to have the biggest impact on executions in Tennessee in coming years. All executions in Tennessee are currently on hold while state courts review the lethal-injection protocol. In terms of individual cases, federal district judges and the judges on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals are the people whose actions are going to determine how many executions we see in Tennessee in the next few years.

Vandiver: While the Public Safety Commissioner is in a position to influence public opinion on capital punishment, it is judges who are going to have the biggest impact on executions in Tennessee in coming years. All executions in Tennessee are currently on hold while state courts review the lethal-injection protocol. In terms of individual cases, federal district judges and the judges on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals are the people whose actions are going to determine how many executions we see in Tennessee in the next few years.

Another development is the decreasing number of death sentences in Tennessee. According to data gathered [by the] Bureau of Justice Statistics, twenty-seven death sentences were imposed in Tennessee in the first decade of this century, compared to fifty-seven imposed in the 1990s. This trend is occurring across the country, not just in Tennessee. It is not clear whether this is due to prosecutors requesting death sentences less frequently, juries imposing them less frequently, or both, but it is a striking change.

Chapter 16: If you could sit down with Governor-elect Haslam and discuss the future of the death penalty in Tennessee, what would you want him to know?

Vandiver: I would urge Governor Haslam to focus on the best use of the state’s resources in order to provide the maximum in public safety. For example, I am troubled by the decreasing clearance rate for homicides. In the 1960s, the police cleared over ninety percent of homicides nationally; now they clear only about two-thirds. This means that a lot of people are literally getting away with murder. Increasing the number of homicides we solve would be far more beneficial to victims’ families and to the public in general than focusing an enormously disproportionate amount of effort on a handful of capital cases.

I would also ask Governor Haslam to review the case of Paul House, who spent twenty-three years on death row in Tennessee for a crime he did not commit. Ten of those years were after DNA cleared him of the sexual assault associated with the homicide of which he had been convicted. Despite overwhelming evidence of his innocence, [in 2006] Mr. House barely prevailed in the U.S. Supreme Court. Without the extraordinary dedication of his appellate attorneys and excellent advocacy work on his behalf, Mr. House would not have been exonerated. Any governor who is willing to preside over executions must reflect deeply on these cases and what they indicate about our system.

Chapter 16: In its endorsement of Haslam, a Republican, for governor, The Tennesseean fudged on the death-penalty issue, saying that since all the major candidates share the same view on social issues (all favored the death penalty), the election came down to who can best run the state. As Tennessee’s New Abolitionists makes clear, gains made by the abolition movement tend to be reversed during times of economic distress and war. Is The Tennessean truly being pragmatic here, or is it playing into the hands of those who would use the economic crisis and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq to divert public attention away from progressive issues like abolition?

Vandiver: As people focus on these issues, their attention is diverted from progressive reforms and often attitudes harden. On the other hand, the current economic situation demands that all levels of government examine expenditures and search out areas of waste and excessive spending. There is no doubt that a criminal justice system with capital punishment costs more than a system without the death penalty. This excess expenditure could perhaps be justified if the death penalty offered benefits not available from any alternative (and cheaper) form of punishment. Three decades of extensive and careful social-science research indicates, however, that the death penalty offers no consistent benefits to society in terms of public safety and undermines the equal administration of justice.

Chapter 16: How would you explain the concept of restorative justice, which seeks accountability rather than retribution, to a victim of violent crime?

Vandiver: I’m having a little difficulty with this question. The topic of restorative justice is very broad and the topic of victims of violent crime is very broad; the two have only a narrow overlap that is relevant to the death penalty. A very few victims’ families have had restorative justice based mediation sessions with the offenders, and these families have generally found the experience to be beneficial. But this approach is most definitely not something that would be appropriate for many, or perhaps most, homicide victims’ families, and so the question, as it is relevant to capital punishment, deals with an extremely narrow segment of victims’ families. Many victims’ families who oppose execution do so for reasons unrelated to restorative justice. And of course many victims’ families support the death penalty. Other families are divided on the issue. There is a great need for more research on what can be done both within and outside of the criminal justice system to offer support and assistance to the families of homicide victims.

Margaret Vandiver and Pete Gathje read from Tennessee’s New Abolitionists at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Memphis on January 15 at 1 p.m.