Loss, Life, and Hope

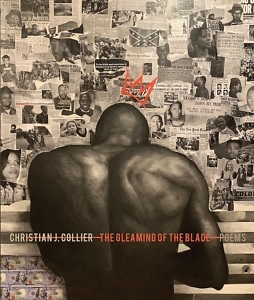

Poet Christian Collier on craft, engaging an audience, and his debut collection, Greater Ghost

Poet Christian Collier’s work has appeared in such publications as Hayden’s Ferry Review, North American Review, Poetry, and Grist: A Journal of the Literary Arts. His chapbook The Gleaming of the Blade was a 2021 Editors’ Selection from Bull City Press, and his poem “Intervention” won the 2022 Porch Prize for Poetry. Greater Ghost, his first full-length collection, takes readers on a journey through all the ways one might be haunted, all the various ghosts that might visit a person. In these poems, Collier focuses on loss and grieving while managing to infuse every poem with a pulsing, insistent life.

Collier lives and writes in Chattanooga. He spoke with Chapter 16 on a streetside patio in early October. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: Christian, your name has been around our town for many years, so it is a pleasure to finally meet you, especially with the buzz around Greater Ghost. How does it feel to “debut” after writing, working, publishing for as long as you have?

Christian Collier: It feels good! For me, in the last month before something gets published, something like a book project, it gets really weird. I feel all the things. And this time around, I’ve been taking a lot of inventory of my journey. There have been so many miles put on my vehicles going somewhere to jump in front of people and do poems, so much learning, and I am so grateful because it has taken literally all of that to reach the point now where I’m confident in the book. I think it’s pretty good.

Chapter 16: Poets, maybe more than any other creative writer, put work into the world in these bite-size pieces, and then if you are lucky and also great, like yourself, you end up getting to put them together in a collection. You might include pieces that were originally published some time ago, so they have a longevity that breathes a little differently. Is there a poem in Greater Ghost that has lived inside you longer, that has a different staying power than the others?

Collier: Yeah, there are several. I started actively writing toward the book in 2019, but there are poems that are, granted they are in a different shape now, but they are much older than that. You know, I feel like I’ve hit that point of fandom where I mention this all the time, but are you familiar with the visual artist Mark Bradford?

Chapter 16: No. Should I be?

Collier: Well, Mark Bradford changed my life. He completely changed the way I work. He’s responsible for what I call my second great epiphany. Mark Bradford builds up these very elaborate pieces; he works very large, often using end papers — like for hair — as his paint. He uses a lot of water and puts up layers of this stuff, and then he’ll get power tools and start taking layers off. He has said, “Often I don’t know what I’m going for or what I want to say until I start pulling different layers out.” And I’m watching him on YouTube when the thought hits me: What if I were to apply this same line of thinking to text? And then all the doors opened. So I no longer see text as a precious thing; it’s all malleable to me. Just because something is “done” doesn’t mean it’s done with what it has to say or can say. Because of this approach, there are pieces from 2006 in there, but they’ve been yanked out, gutted, and remixed. But there are one or two that I think are pretty much as they were back in 2006. “The Return” is one from around that time.

Chapter 16: I am curious about how you came to build this collection. So many of the poems, starting from that very first line, “I am soaked in my losses,” feature grief as well as images of water or fluidity. Once you decided that you were building a book, did you know it was going to be about grieving? Did you know that the thread of water would be there, or did that come from this process of removal and addition and letting the thing flex?

Collier: In a word, no. When I started, I had just abandoned a manuscript that I’d spent at least three years on. And I wasn’t sure what was next. But I went to the Frost Place in New Hampshire, and my workshop leader was Tyree Daye. As soon as we began, at 5 o’clock in the afternoon, Tyree said, “You guys have poems due tomorrow morning.” So every day, we wrote. You didn’t have time to overthink it. It was just like, ok. I guess we’re writing poems. I wrote every day that week, and the poems were bringing me into the work in ways that I had not ever allowed before. When I came back, I laid everything out and looked at it. And around that time, I have the Mark Bradford epiphany. And then, this thought hits me: What if I were to write into and explore the theme of ghosts. Because we have the on-the-nose ghost reference to someone who has passed away, but also memory can be a ghost. And I thought I’d just write toward that and see what happens.

So that’s how it began, and I think some people are like, “I’ve written this thing, and now it’s going to turn into a book.” I’ve never had that, but when my chapbook got picked up, I thought, well maybe this can, too. Because once you get familiar with the process and have an idea what an editor is looking for, then you’re able to hammer something into place. I thought maybe this could be a book. But even up to the point where the good people of Four Way sent the contract, I wasn’t sure. Only then did I say, ok, now it’s a book. Or will be. But all that while, I just saw them as poems doing a particular thing. I was really intentional, though. I wanted it to exist with a press that would believe it in as much as I did and fight for it. I didn’t want to just turn it over to somebody and not see it for two months. I wanted it to be able to have a life and find its audience, so my stubbornness in terms of who I wanted to have it paid off, because Four Way is on that list.

Chapter 16: You recently got a poem in The Atlantic. How has that been? Is that the biggest audience for your poetry so far?

Collier: Well, I’ve had a few in Poetry magazine, but yeah, that’s the biggest, or at least the most name recognition. Way back when, I was featured on The Guardian, but those things come and they go, and then you’re back to it. Especially in a town like Chattanooga — that’s what I love about Chattanooga — it’s kind of punk rock in that it keeps you humble. People are like, “Oh that’s great,” and then three months later, you go back to being just you. But The Atlantic feels a little different, I think, just because it’s a brand that even if you don’t read, you know.

Collier: Well, I’ve had a few in Poetry magazine, but yeah, that’s the biggest, or at least the most name recognition. Way back when, I was featured on The Guardian, but those things come and they go, and then you’re back to it. Especially in a town like Chattanooga — that’s what I love about Chattanooga — it’s kind of punk rock in that it keeps you humble. People are like, “Oh that’s great,” and then three months later, you go back to being just you. But The Atlantic feels a little different, I think, just because it’s a brand that even if you don’t read, you know.

Chapter 16: Poetry is no small thing, but it has a fairly niche readership doing a particular thing, whereas The Atlantic might be picked up for lots of reasons. You may not have ever read a poem before and find Christian Collier’s poem there, and all of a sudden you realize, “Oh wow. I didn’t know I loved poetry, but now I do.” So that’s an elevation, in terms of audience. Do you have people calling you with congratulations?

Collier: To a certain degree, yeah. My wife rags on me all the time because she says I never get excited about things, and I do, but I’m just not outwardly excitable very often. And I don’t want to sound like a total homer, but to me, the work is what I get jazzed about. Or being able to be in conversation with people that I’ve loved and studied. Like the fact that I met Gary Jackson and Joy Priest. I’ve read them for years! But for other people it is. My dad is ecstatic. I’m also getting emails from people around the country and around the world; I got one from the UK. So that’s neat.

Chapter 16: Speaking of audience, you’ve done a lot of spoken word over the years, and there’s something profoundly different about reading a poem to a live audience. What do you get from a reading? What’s great about it, and what can be horrible?

Collier: Oh, there’s so many things. Being in front of people has taught me a lot. Way back when, there were a lot of times when I was on bills, hitting stages where the audience was a lot of couples on a date night, possibly at the suggestion of somebody’s girlfriend or wife, and the guy’s just there. And I would see that half the equation wouldn’t really care. It dawned on me that to be successful, I have to give them the energy of whatever they were listening to in the car on the way to the show. I have to match that energy to get that buy-in, to where they might say, “I don’t usually like poetry, but I like you.” Once I establish that trust, I can stretch out and take them where I want to. But I have to get that buy-in first.

That has informed so much, like teaching — where I have to give kids something that’s in their wheelhouse, so maybe I start with a Hanif Abdurraqib poem about Drake, and then I work my way back to John Donne. But I get that buy-in first. It’s taught me a lot of different things. I think the works that we make are documents. There isn’t only one way to read a poem. It doesn’t mean it can’t be something else. And when we’re in front of people, we have the opportunity to share and create moments and do different things with the work that we can’t necessarily do on the page. When things are great, there’s a genuine connection and a certain energy. When things are not great, it doesn’t really have anything to do with getting up in front of people. Because even when there’s only two people there, there’s still two people.

Chapter 16: And they want to hear your work.

Collier: Yeah, and you don’t want to shortchange them. The things that suck are after-stage-adjacent, like realizing there’s nowhere to get food at 10 at night in Minnesota or wherever. Or being somewhere and the Uber situation is shaky at best, and you’ve got to get back to the hotel. Or going over two hours away with the promise of money and then there is no money, and you still have to drive back and go to work. Those are things that are not great, but even when you’re in front of people who don’t care, that’s still an opportunity to learn something or try something. I am stunningly blessed 9 times out of 10 to end up in spaces where I don’t have to compete with the bartender and the people are there to see me or for the event.

Chapter 16: The way you’re describing it puts me in mind of a band or singer-songwriter, making the rounds, trying to break on the scene. And not to say that poets are better than fiction writers, but fiction writers don’t have to do that. They’re not booking gigs and making sure they can get an Uber. There’s an appeal to that hustle and a vulnerability to it.

Collier: Any time that we tell people to follow your dream, when you’re really going for it, there’s always that vulnerability. Because it’s ever-shaky ground. It’s an adventurous way to go about this thing called life.

Chapter 16: Was poetry always your dream?

Collier: No, for the longest time, I thought I was going to do visual art. That’s what I started training in, and then in 1998, I stumbled into poetry for some reason. I don’t know why. I know the impetus of what I wanted it to do, but I don’t know why poetry was the thing. I was trying to woo this girl I went to high school with, and for whatever reason, I thought poetry.

Chapter 16: Do you have thoughts you’re willing to share about AI poetry?

Collier: Oh yeah. To me, it’s just another tool. I think automatically, when something gets introduced, especially with technology, it’s easy for people to see how this could go wrong. But it’s similar to what happens with airline pilots, where they get the plane going and then the machine takes over. And I’m not saying we should replace the guy sitting in the seat, but I think there’s a place where there can be a relationship. If you’re curious about how it would sound to try something in your work, you can dump it into a tool, and that result might trigger something else in you. You can have a relationship that’s not totally dependent on the technology.

Collier: Oh yeah. To me, it’s just another tool. I think automatically, when something gets introduced, especially with technology, it’s easy for people to see how this could go wrong. But it’s similar to what happens with airline pilots, where they get the plane going and then the machine takes over. And I’m not saying we should replace the guy sitting in the seat, but I think there’s a place where there can be a relationship. If you’re curious about how it would sound to try something in your work, you can dump it into a tool, and that result might trigger something else in you. You can have a relationship that’s not totally dependent on the technology.

Chapter 16: Yes, what you’re describing is very different from the version of AI poetry described in Ted Chiang’s essay on “Why AI Isn’t Going to Make Art,” where the recipient of the poem couldn’t tell it was AI.

Collier: Well, the reason that was successful was because that person was probably on the younger side of the coin but also probably didn’t read much poetry. You’re not going to fool many people who read poetry. That element of craft is one of the hardest things to replicate, which also gives us a buffer. I know Terrance Hayes uses one of the big programs, and he’ll tell it to read this poem in John Ashbery’s voice just to hear what his work would sound like in that style. And Terrance Hayes is definitely far enough into his career where we’re not seeing that as a problem. It’s just a thing to put something else in the air. Everybody comes to the table differently, and for people who want to use artificial intelligence to try to make it big with poems, my thing would be why not do that with fiction? It pays better. That would be a smarter way to swing it, in my opinion.

Chapter 16: Shifting back to Greater Ghost, several poems in the collection refer to the grief and the loss after miscarriage, which is, as you probably know, often an invisible tragedy that people carry around with them and they don’t often get permission to grieve. That’s true for the person who was pregnant, but it’s also true for their partner. You rarely hear about it from the partner’s perspective. Did you feel like you were doing something remarkable, something different? Or maybe after the fact, did you recognize that you’d addressed something that most men don’t talk about?

Collier: I never thought about it until I read “First Time After” at an open mic, and I had somebody come up to me, saying, “I don’t think you know what you have with this.” Life has a way of finding its way in. And for me, I’m somebody who’s trying to turn every subject around and see it from all these different angles. By chasing obsessions, that’s how I get those series of poems. And that’s all I was doing, just doing the work. Later in the process, I realized that if I put these with the love poems, they form a complete narrative, and that was something I didn’t intend when I was just punching in the words. But in doing that, it allowed me to move farther beyond the origins of the miscarriage. It’s interesting to have it resonate with people because it was just me sitting down and doing the work.

Chapter 16: You’ve mentioned that you love Chattanooga, but do you claim a Southern identity? Do you feel like this collection speaks from that identity?

Collier: Oh sure. And yes, I do, especially with the way family is treated and maybe it’s not solely Southern, but it’s definitely true in the South, like in “The Men in My Family Disappear,” being in the country for a funeral, and we start shooting hoops. The South is a very haunted region, and I come from a people who believe that the physical end is not the end, and that you carry your people with you wherever you go. And I’ve always felt like that, even outside of the poems. Wherever I go, I’m bringing my people with me.

Chapter 16: And your dedication in the book is to your people.

Collier: Oh yeah, and I think it’s very Southern in that aspect, of just the fact that you don’t forget the people that you come from. They’re always with you, and that’s such a big way to show love. I also don’t think that love dies. I think that even if you’ve had the worst relationship, if you love that person, part of you will always love that person. I think it’s very hard, once somebody has awakened something in you that was not previously there, it’s very hard to turn that off or discard it.

Chapter 16: And I’m not sure we would want to, right?

Collier: Yes. Who would you be at that point? So yeah, I think it’s Southern, even in the way that it goes about music. There’s a blues motif that appears throughout. “In the Time of Dying, Meet Me” is very much a blues poem, inspired by Blind Willie Johnson.

Chapter 16: As you said, the South is a haunted place, and in some ways we keep our worst ghosts out on display. It’s an interesting dynamic to lean into different versions of those ghosts, the negative haunting and the positive haunting, and when you describe taking your people with you, it feels positive, like a comfort.

Collier: I think it’s a little bit of both. Danez Smith has a poem with a line that essentially says you can’t be who you want to be until your parents have passed on. There’s definitely some truth to that, but it’s also kind of sad how often a person has to tamp down who you are until people that we were once accountable to can no longer say something that triggers the 14-year-old you and that sense of shame. I think there’s always that duality. Each of us carries a shadow self with us. We are at all times both good and bad, light and dark, and the truest things are things that speak to both of those. And maybe that’s just life.

Chapter 16: Like the love poems and the miscarriage poems being part of the same whole. Greater Ghost is about loss; however, it’s also inherently about life and hope. So maybe that’s why? To be alive you have to have both?

Collier: Yes. Definitely.

Sara Beth West is a librarian and a freelance writer focusing on book reviews and author interviews. In addition to Chapter 16, publications include Shelf Awareness, BookPage, Southern Review of Books, and more. She lives in Chattanooga.