Love and Theft

Exploring the idea of an American national literature, Jason Richards finds a complex play of imitations

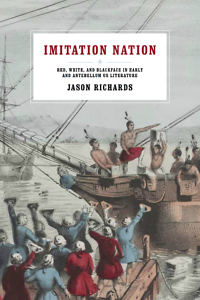

Jason Richards’s lively and sophisticated new book, Imitation Nation: Red, White, [***]and Blackface in Early and Antebellum US Literature, hinges on couple of related premises about identity. Because no essential self exists independent or free from outside influences, people identify themselves in and through the others in their midst. Every assertion of self, it follows, involves imitation of one kind or another.

The literary history of the United States reflects these basic premises. African Americans, Native Peoples, and European Americans, depending upon the writer and the historical context, have complicated the relationship between oppressor and oppressed by imagining each other’s identities. The most creative and confounding examples of this imagining happened when these groups imitated one another. Richards uses the terms “redface,” “whiteface,” and “blackface” to describe these imitations.

The literary history of the United States reflects these basic premises. African Americans, Native Peoples, and European Americans, depending upon the writer and the historical context, have complicated the relationship between oppressor and oppressed by imagining each other’s identities. The most creative and confounding examples of this imagining happened when these groups imitated one another. Richards uses the terms “redface,” “whiteface,” and “blackface” to describe these imitations.

On the surface, promoters of American literature between the founding era and the Civil War craved originality. American writers in the New World sought to be different from Europeans in the Old World, but they also wanted to promote white racial purity against Native peoples and enslaved Africans. Richards shows how that quest was never pure. Despite claims to the contrary, “originality” meant relentless imitation on multiple levels.

The central conceptual move in the book works like this: the more a chosen identity defines itself as decisively different or unique from some other identity, the more it implicates itself in that other identity and others besides. For example, America of the early republic was a “settler nation…both colonized and colonizing at once.” Striking out on their own, Americans wrote about “going native” (“redface”) to distinguish themselves from their former oppressors, the British, even as they also wrote about exterminating Native peoples.

Contradictory impulses like these didn’t preclude American imitation of British literary forms either: “To read imitation as a sign of failing at originality, to see originality and imitation as opposites, is to miss how European influence is part of what makes American literature ‘distinctive,'” Richards writes.

Imitation Nation is an academic book that could be shelved with works of postcolonial theory, transnationalism, critical race theory, and American literary nationalism. Luckily, Richards writes with genuine clarity, so those interested in academic debates can see just where and how this book fits within those schools of thought. The book’s occasional complexity stems from the dynamic interplay between these theoretical positions and the multiple identities the author finds at work in each text he treats.

Imitation Nation is an academic book that could be shelved with works of postcolonial theory, transnationalism, critical race theory, and American literary nationalism. Luckily, Richards writes with genuine clarity, so those interested in academic debates can see just where and how this book fits within those schools of thought. The book’s occasional complexity stems from the dynamic interplay between these theoretical positions and the multiple identities the author finds at work in each text he treats.

Lay readers can nonetheless learn a great deal about oft-overlooked works of American literature-Charles Brockden Brown’s Edgar Huntly (1799) for one-while finding plenty to chew on in classics like Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Melville’s Benito Cereno. Along the way, Richards injects offhand observations that make even familiar material fascinating. He notes, for example, that the letters between John and Abigail Adams “sometimes read like America’s first epistolary gothic novel.”

By the time the book arrives at Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the spirit of Imitation Nation grows ever clearer. At least since James Baldwin attacked Uncle Tom’s Cabin for its use of common figures in blackface minstrel shows popular at the time, Stowe’s novel has inspired intense debate. For years it was condemned for its racism, but more recent interpreters have emphasized its antiracism. Richards digs in at the crossroads: “Stowe’s book, it seems to me virtually balances racism and antiracism, negative stereotypes and abolitionist virtues. Her racial ambivalence … yields a text that speaks with a forked tongue, much like minstrelsy itself, leaving ample room for praise and condemnation.”

On its face, this seems like equivocation until the reader notices the subtle use of “forked tongue” to describe a book with a religious message at its heart. The devil, as it turns out, is once again in the details.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses having to do with American culture and thought. He is also a regular blogger for the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH).