Making Beautiful Stories

The Southern Festival of Books is a lot like the state fair—but better

When I was a young girl I went to the Michigan State Fair for the first time, and suddenly my world was bigger. I saw my first live cow and my first live pig. I rode my first Ferris wheel. I heard the Supremes—who, according to family gossip, dressed to emulate my mother—but I also heard country music for the first time. It was at the Michigan State Fair that I first saw white people in overalls and blue jeans. It was 1966, I was seven, and 1.2 million people attended the fair that year.

When you’re four feet tall, the loud and the crowd on the ground, the competing smells of stink and sweet, overwhelm. From the top of the Ferris wheel, every bit had a place in a pattern of pretty. Pulled upward into the night sky I knew this: here was something where nothing had been and nothing would soon be again, but for a few days a very special flavor of fun had rolled into town, set up tents, and invited me in. I was profoundly delighted. I didn’t want the ride or the music or the night to stop. The dark had become velvet.

When you’re four feet tall, the loud and the crowd on the ground, the competing smells of stink and sweet, overwhelm. From the top of the Ferris wheel, every bit had a place in a pattern of pretty. Pulled upward into the night sky I knew this: here was something where nothing had been and nothing would soon be again, but for a few days a very special flavor of fun had rolled into town, set up tents, and invited me in. I was profoundly delighted. I didn’t want the ride or the music or the night to stop. The dark had become velvet.

Like the Michigan State Fair, Humanities Tennessee’s annual Southern Festival of Books has a charmed location in the center of the city, stretching from Legislative Plaza to the Nashville Public Library a block away. From near the top of the steps leading to the War Memorial Auditorium, it’s easy to see the discrete pieces of the pattern: the brightly striped awnings of the booths that line the plaza, offering all manner of book-related information and souvenirs; the children’s stage, where itty-bitties grip balloons, chatter back to stories, and sing along with songs; the music stage and the poetry stage, where folks shuttle between lyric and lyric; the food trucks lined up on both ends of the plaza; and the giant tent where Parnassus Books—co-owned by novelist Ann Patchett—sells copies of the novels and poetry collections and children’s books and memoirs and histories and cookbooks written by all 275-plus authors appearing at the festival. Beneath the plaza is a labyrinth of chambers and hearing rooms where the business of the state is normally conducted but where so many of the readings and panel discussions take place during festival weekend.

Beautiful as the original Michigan State Fairgrounds were, the setting of the Southern Festival of Books is more beautiful. The plaza provides views that perfectly frame the Tennessee State Capitol, arguably architect William Strickland’s finest building; looking in the other direction, you’ll see our public library, arguably one of architect Robert A.M. Stern’s finest works, where the other half of the festival’s readings take place in beautiful, light-filled rooms lined with books.

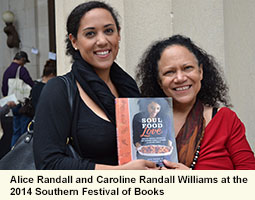

For more than a quarter-century, I watched my daughter, Caroline Randall Williams, grow up on that plaza.

In 1989, she was a toddler in a stroller I pushed across the plaza (and carried up and down all those steps) at the very first Southern Festival of Books. This year, at 28, she will be reading from her first volume of poetry, Lucy Negro, Redux, which poet Thomas Sayers Ellis, co-founder of the Dark Room Collective, described as “part savvy lit crit, part Blues chart, part hip revenge-femme-lyric, part imagined interracial romance saga disguised as poems….” The poems are very much of the body and of the page, and they should probably make a mama blush, but all I want to say is, “It was worth carrying you up and down those plaza steps for all those years.”

I still have a picture of Caroline and me that was taken at the second Southern Festival of Books and published in The Tennessean, Nashville’s daily newspaper. The caption reads, “A balloon is forgotten as Caroline Randall, 3, enjoys a collection of Eudora Welty’s photographs with her mother, Alice, at the Southern Festival of Books on Legislative Plaza.” The photo is accompanied by a very short article—so short I can quote it in its entirety:

Caroline Randall’s eyes moved carefully across the pages of a book of Southern photography that her mother, Alice, was thumbing through on Legislative Plaza.

Caroline, like many people attending the second day of the Southern Festival of Books, is not just an avid book-lover. The 3-year old also likes to “write.”

“I make beautiful stories,” Caroline said shyly with a smile. Caroline makes songs, too, her mother said.

Stacks of books everywhere pulled passers-by to booths, and authors considered themselves as lucky as the readers to be there.

For twenty-seven years, some of our best mother-daughter days have been at the Southern Festival of books. There’s always an abundance of authors and readers, and all kinds of books, but we have especially loved photography, fiction, children’s books, cookbooks, and poetry. For Caroline, the wilder and more experimental the better. In our family the Southern Festival of Books is a holiday more important than the 4th of July or Easter, and we prepare for it the way we prepare for Christmas.

Thanks to the festival, Caroline has had close encounters with a wide variety of book folk, from Morgan Entrekin to Julia Child, from Ron Rash to Charles Blow. She was a junior at Harvard when I got Rash to sign a copy of Serena, his retelling of Macbeth, and put it on the very last reading list I ever made for her. After that, I was too busy reading from the list she was making for me.

Thanks to the festival, Caroline has had close encounters with a wide variety of book folk, from Morgan Entrekin to Julia Child, from Ron Rash to Charles Blow. She was a junior at Harvard when I got Rash to sign a copy of Serena, his retelling of Macbeth, and put it on the very last reading list I ever made for her. After that, I was too busy reading from the list she was making for me.

Over the years we have moved back and forth across the divide between author and audience. Caroline was with me when I brought my first novel, The Wind Done Gone, to the festival in 2001. Years later, away at boarding school and then college, she missed many festivals, but more and more—as she grew and learned and read—our conversations centered on books and authors. And in that way, even from a distance, we still shared the festival.

Before the whole world knew Ta-Nehisi Coates, Caroline knew his work and knew that he was coming to the Southern Festival of Books and told me to make sure to meet him. In recent years our festival weekends have focused on readings by her friends and graduate-school professors at Ole Miss: we’ve savored The Tilted World, Beth Ann Fennelly and Tom Franklin’s tale of the swollen Mississippi River; Ropes, Derrick Harriell’s elegiac poems of boxers in conversation with one another; and Delta Dogs, photographs by Maude Schuyler Clay that underscore the humanity binding white and black people beyond race.

In 2012 we presented The Diary of B. B. Bright, Possible Princess, a middle-grade novel and our first jointly written book, at the festival. That was one of the best days of my life. There was standing room only, and the place was full of young readers who loved B.B., the character Caroline first invented when she was 3—a black fairy-tale princess who was in very significant ways conceived in the sales tent at the Southern Festival of Books, as we scanned through book after book, fruitlessly looking for someone like her.

This year Caroline and I will be presenting another collaborative project: Soul Food Love: Healthy Recipes Inspired by One Hundred Years of Cooking in a Black Family. This book owes its existence, in large part, to the inspiration of John Egerton, author of Southern Food (and many other books, including the Robert Kennedy Award-winning civil-rights history, Speak Now Against the Day). John was present from the very inception of the Southern Festival of Books, and he became my mentor. He was the person who recognized, almost before Caroline and I did, that our family culinary history would be of value to other families, and it breaks my heart that John didn’t live to see this book into print. I may appear to be standing up when we present Soul Food Love, but inside I will be tore down. Presenting this book at John’s festival is going to be almost impossible to do without crying.

This year Caroline and I will be presenting another collaborative project: Soul Food Love: Healthy Recipes Inspired by One Hundred Years of Cooking in a Black Family. This book owes its existence, in large part, to the inspiration of John Egerton, author of Southern Food (and many other books, including the Robert Kennedy Award-winning civil-rights history, Speak Now Against the Day). John was present from the very inception of the Southern Festival of Books, and he became my mentor. He was the person who recognized, almost before Caroline and I did, that our family culinary history would be of value to other families, and it breaks my heart that John didn’t live to see this book into print. I may appear to be standing up when we present Soul Food Love, but inside I will be tore down. Presenting this book at John’s festival is going to be almost impossible to do without crying.

When I look back at the picture the Tennessean photographer took of Caroline at three, what surprises me most is what hasn’t changed about Caroline—and what hasn’t changed about the festival.

The blue bow, something from a present that she seized and employed to tie her hair up high and cattywumpus, is a tell that she will make new things out of old things. My evening purse slung on her wrist is a tell that she will follow in my footsteps. The swashbuckling way she criss-crossed the straps of her kilt across the front of her chest instead of her back is a tell that she will be original and bold. The hot pink tights I’m wearing because she made me wear them is a tell that she will be bossy. The curiosity in her eyes is a tell that her perspective shifted early, and will always be a little bit different.

Way back then, Caroline had already been to the tiptop of the stairs rising above Legislative Plaza—rising above it like a Ferris wheel. From way up high, everything fits in. Everything is beautiful; all the people belong. All the stories come together and make up one big story.

And the festival—what hasn’t changed about it? Twenty-seven years ago, if you had asked me about the best time to visit Nashville, I would have said the second weekend in October—the weekend of the Southern Festival of Books. It’s a guaranteed good time. Rain or shine. At the festival, just showing up to hear the same author is considered invitation enough to engage your seatmate in conversation. Attending the Southern Festival of Books is the closest a visitor can come to being an instant insider in Nashville, where the New South begins. If you asked me that question today, I would say the same damn thing.

Copyright (c) 2015 by Alice Randall. All rights reserved. Nashville novelist Alice Randall is the author of The Wind Done Gone, Pushkin and the Queen of Spades, Rebel Yell, and Ada’s Rules. Her latest book, Soul Food Love, is a cookbook memoir co-written with her daughter, Caroline Randall Williams.