Making Believe

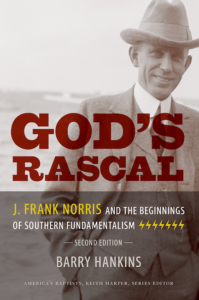

God’s Rascal examines the life of fundamentalist J. Frank Norris

“It doesn’t have to be true. It just has to be believed.” This grim adage comes from Alexander Nix, former CEO of Cambridge Analytica, a political consulting firm that once served the presidential campaigns of Ted Cruz and Donald Trump. What the average Joe calls lying, influence peddlers call winning. Conscience, in such contexts, is a show of weakness.

The threat unprincipled parties pose to an anxious and despairing populace is nothing new. In this sense, the story Barry Hankins tells in the new edition of God’s Rascal: J. Frank Norris and the Beginnings of Southern Fundamentalism is almost comforting in its familiarity. Through careful study of the voluminous writings of his subject — a pastor, pundit, radio personality, and sexual predator born in Alabama in 1877 — Hankins demonstrates that the multi-pronged cultural crises that threaten American public life follow a familiar pattern that’s been jumping the fences of politics, religion, and media all along.

“If fundamentalism had not existed,” Hankins tells us, J. Frank Norris “would have invented it.” Why? Because it functioned as a vehicle with which to stir up a crowd, target perceived enemies, and cultivate a following. As a student at Baylor University in 1902, Norris developed a taste for cobbling together a kerfuffle after a dog was smuggled into a chapel service and the president of the university seized it and threw it out of a window. Despite the president’s apology, Norris contacted the local Humane Society, notified the university trustees, and organized a protest which eventually led to the president’s resignation.

Whether denouncing the theory of evolution, maligning Roman Catholics, or praising the Klan for successfully opposing a public speech by W.E.B. Du Bois, Norris went on to stoke and capitalize upon whatever social strife would strengthen his position as a professional God talker commandeering First Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas. According to some accounts, this included setting the place on fire.

Whether denouncing the theory of evolution, maligning Roman Catholics, or praising the Klan for successfully opposing a public speech by W.E.B. Du Bois, Norris went on to stoke and capitalize upon whatever social strife would strengthen his position as a professional God talker commandeering First Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas. According to some accounts, this included setting the place on fire.

In a turn reminiscent of our own news cycles, Norris’ desire to police other people’s reading wasn’t limited to attacking pastor colleagues who didn’t share his literalistic interpretation of scripture (“If you deny the Genesis account of creation, you had just as well throw the Bible in the fire.”). It also included an effort to remove texts from public school libraries that failed to adhere to his vision of what was “biblical,” a word that, in Norris’ hands, came to function as a marketing term.

Relatedly, Norris proved nimble in his attempt to fuse together one issue with another when he targeted liberal pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick’s church, Park Avenue Baptist in New York City, for having a Rockefeller-funded ballroom: “Evolution and the dance are to each other as cause and effect.” In his salvos, racism and prurience often operated in tandem. The latter would prove useful when he killed an unarmed man who showed up at his office with a grievance. He was acquitted after aspersions were successfully cast upon a witness for the prosecution who was a divorcée.

Norris also understood that association is a form of currency, and Hankins successfully traces his efforts to ingratiate himself to William Jennings Bryan, Herbert Hoover, Pope Pius XII, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. These efforts sometimes took the form of privately urging particular figures to run for elected office without disclosing that he was writing similar letters to their opponents. Similarly, he backed Roosevelt’s New Deal until he picked up a second church in Detroit and started siding with General Motors against the labor movement. His transactional understanding of relationships extended to his son, whom he practically disowned after the son started a church of his own.

By showcasing Norris’ pushing of premillennialism, the state of Israel as a sign of God’s faithfulness, and a belief in a coming Rapture (later popularized in the Left Behind book and film series), Hankins reminds us that Christian Zionism among fundamentalists dates back to the 1930s; but here again, Norris knew how to incite strategic euphoria while holding certain cards to his chest. Of Benito Mussolini, he would offer this: “I will not say that he is, or that he is not the Beast.” He drew a line at one form of anti-Semitism, but for solidly Christian supremacist reasons: “We believe when Christ comes the Jews will be converted, and become the world’s greatest evangelists. … Why kill them off if they are to be the world’s greatest evangelists?”

Through Norris, Hankins gives us a character type, wearingly familiar in our day, of a talented and abusive man who collects people and seeks to retaliate against and even destroy them once they slip out of his control. And all of this in analog, without the magic power of digital technology or interconnected networks. It’s a grim tale, but it can render our own heady present into something that feels a little more manageable.

David Dark is the author of five books, including The Possibility of America, Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious, and The Sacredness of Questioning Everything. He lives in Nashville and teaches at Belmont University and the Tennessee Prison for Women.