Meeting in the Middle

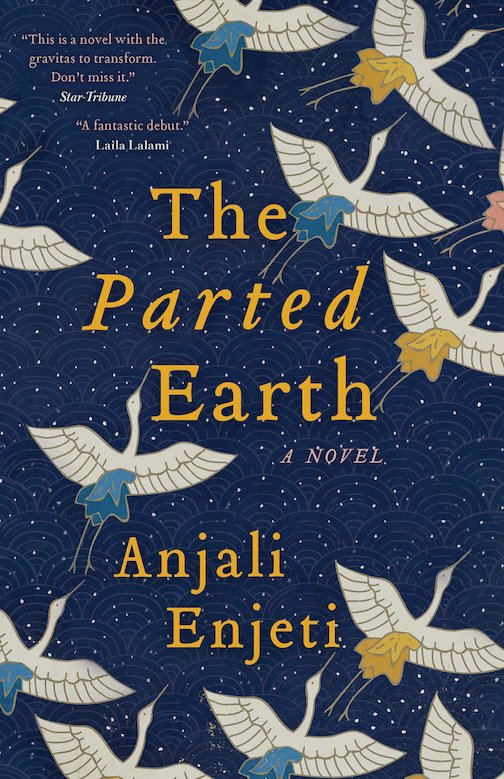

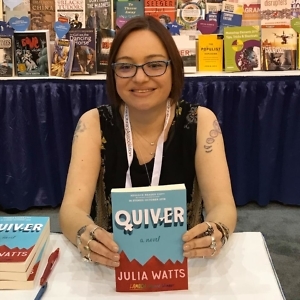

Julia Watts’s new novel for teens finds room for friendship in the so-called culture wars

Julia Watts’s heart is in Appalachia. A native of southeastern Kentucky who makes her home in Knoxville, she has lived in Appalachia all her life. Watts writes books for adults, teens, and children about “Appalachians who don’t fit the stereotypes and often who don’t fit in,” according to her website.

Her newest novel, Quiver, is set in East Tennessee and tells the story of two teens who find themselves new neighbors and, eventually, friends. Libby, the oldest of six children, is from a family of strict evangelical Christians who practice the “Quiverfull” lifestyle, one that leans heavily on patriarchal systems. Zo is a gender-fluid teen whose liberal, feminist family has moved to the country from Knoxville. Libby and Zo’s budding friendship, what they learn from one another, and how they grow in the process is at the heart of the Lambda Award-winning author’s tale.

Her newest novel, Quiver, is set in East Tennessee and tells the story of two teens who find themselves new neighbors and, eventually, friends. Libby, the oldest of six children, is from a family of strict evangelical Christians who practice the “Quiverfull” lifestyle, one that leans heavily on patriarchal systems. Zo is a gender-fluid teen whose liberal, feminist family has moved to the country from Knoxville. Libby and Zo’s budding friendship, what they learn from one another, and how they grow in the process is at the heart of the Lambda Award-winning author’s tale.

Watts teaches at South College and in Murray State University’s low-residency M.F.A. program. She recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email about the new novel and what it was like to craft characters from both ends of the so-called culture wars. The nonstandard pronouns she uses to refer to Zo are a reflection of the character’s gender-fluid identity.

Chapter 16: You write with such specificity about this type of fundamentalism and the “Quiverfull” lifestyle. Have you known religious fundamentalists like Libby’s family? Or was this all research? Or a bit of both?

Julia Watts: I’d have to say a bit of both. I was raised in rural southeastern Kentucky, so I was surrounded by religious fundamentalism. I grew up in a mainstream Southern Baptist church, which, by definition, was fundamentalist. There was Bible drill (which I was danged good at, by the way) and Vacation Bible School and rousing hymns like “Onward Christian Soldiers” and “Nothing But the Blood of Jesus.” However, this was a downtown church in a big, fancy building, and it was very mainstream, compared to the more country churches.

In school, I was very aware of the kids who went to churches that were more restrictive than mine, especially the Holiness girls who never cut their hair and had to wear skirts or dresses even in gym class. I remember helping one of these girls safety-pin her skirt together so that she could jump on the trampoline without a wardrobe malfunction!

Despite my early exposure to fundamentalist Christianity, though, I still had to do a lot of research on the Quiverfull lifestyle, which didn’t really start taking off until the mid-1980s with the publication of Mary Pride’s book The Way Home: Beyond Feminism and Back to Reality, which advocated Biblically-mandated gender roles for men and women, with women staying home and having as many children as the Lord allows. I read lots of books by Quiverfull authors and blogs by Quiverfull moms, who are still part of the movement.

For a great work of investigative journalism on the subject, Kathryn Joyce’s book Quiverfull: Inside the Christian Patriarchy Movement was absolutely indispensable, as was the No Longer Quivering blog by Vyckie Garrison, a former Quiverfull wife and mother, who speaks out about the spiritual abuse she experienced in the movement. I would definitely recommend Joyce’s book to readers of my novel, who want a broader perspective on Quiverfull; I certainly don’t want to give the impression that Libby’s family is representative of all families who practice this lifestyle.

Chapter 16: I like how Libby’s revelation that her father is controlling—“None of this comes from God. It comes from people saying what they think God wants”—occurs to her first and is then validated at a later date by others (Dr. Nasour and even her own mother). Was it important to you that Libby come to this understanding on her own?

Watts: Thanks for noticing this! Yes, it was very important to me that Libby has this realization herself. Just like with any other big change in life, the discovery had to come from within. However, I think it was also important for Libby to have other people validate this discovery, whether it be a benevolent stranger like Dr. Nasour or her own mother, who has been trapped in the same situation.

Chapter 16: I like how Libby continues her relationship with God (just a much healthier one)—she tells Zo she’s attending a Methodist church with her grandmother—because I think turning away from religion altogether would have been unrealistic for her. Did you always know this would be her path?

Chapter 16: I like how Libby continues her relationship with God (just a much healthier one)—she tells Zo she’s attending a Methodist church with her grandmother—because I think turning away from religion altogether would have been unrealistic for her. Did you always know this would be her path?

Watts: While part of me would have loved for Libby to rebel against her upbringing by becoming a Unitarian Universalist or a pagan or an atheist, I knew any of these moves would be too extreme for her character; she couldn’t realistically move from point A straight to point Z. Also, I didn’t want the book to be against religion and/or spirituality; I wanted it to be against forms of religion that are legalistic and patriarchal. When I started writing Libby’s grandmother, I knew she would be an open-minded Christian who believes that Christians should live in the world and try to make it a kinder place and who uses her faith as a source of strength, instead of oppression. I think finding a healthier form of Christianity was the most realistic path for Libby.

Chapter 16: We come away from this novel knowing a bit more about Libby’s interior life than Zo’s. Was that intentional? Do you think this is Libby’s story?

Watts: I think the story belongs to both characters; however, Libby does go through more radical changes over the course of the book. Zo is being raised in a much more open, accepting atmosphere and so has less to overcome and fewer internal changes to make. That being said, Zo is nursing hir first broken heart, which came about in part because hir girlfriend couldn’t accept hir as gender fluid, so that’s no small matter.

I will say, though, that when I first started this novel, I knew it would be about Libby and Zo’s friendship, but I thought it would be written exclusively from Libby’s point of view. After I drafted a few chapters, it became obvious that Libby is so sheltered that limiting it to her point of view wouldn’t allow me to say what I needed to say. Since it is a book about a friendship that bridges the gap between the two extremes of the so-called “culture wars,” showing both perspectives was important. Instead of being Libby’s story or Zo’s story, it’s the story of Libby and Zo’s friendship.

Chapter 16: Libby’s father believes Zo and her entire family “ask a lot of the right questions … [but] just come up with the wrong answers a lot of the time.” Clearly, the two families are on two sides of the political and theological spectrum. In many ways, our country now feels this divisive. Was this on your mind as you wrote?

Watts: Oh, absolutely! How could it not be? Turn on the TV or go on the Internet, and it’s all red states vs. blue states, Fox News vs. MSNBC. Living in the South and being progressive, these differences are especially apparent on a daily basis because my views are definitely in the minority!

People have come to define themselves so much by their political and theological views that they surround themselves with people who agree with them 100 percent of the time. I feel like it’s healthier if you can still like someone, even if you disagree about quite a bit of stuff. You can still have empathy for your fellow human beings. And these days a lack of empathy happens on both sides of the political spectrum. Yes, you get conservatives demonizing liberals, but I’ve also seen lots of situations in which there’s a lack of empathy from some liberals, such as those who stereotype people from my home region as all being ignorant hillbillies. Because of the divisive nature of our country now, I wanted to write a book about empathy and the things that unite us as humans, regardless of our political or theological beliefs.

Chapter 16: How does teaching inform your writing, if at all?

Watts: Teaching definitely informs my writing. Since writing is something that comes naturally to me, teaching writing forces me to think more consciously about the choices I make—and the tools that I have available to me—as a writer. The thinking I do about writing in order to teach makes me a better writer, and I love working with students at all levels, whether they’re freshman-comp students, graduate students, or groups of adult writers. Sure, writers need privacy and quiet to do their work, but it’s not good to be too isolated or too in-your-own-head either. I love the differing perspectives that I get from students.

Chapter 16: How I love Libby and her determined spirit—and how I rooted for her. Where do you see her in ten years?

Watts: What a great question! I think that with her mom and her grandmother’s support and encouragement, Libby will graduate from high school and go to college. She’ll start out at a community college (in Tennessee she can go for free!) and then go on to earn a bachelor’s degree in nursing at East Tennessee State. In ten years, Libby will be working as a nurse and engaged to a nice guy, who works at the hospital with her—but in no big hurry to get married. She’ll still be a Christian—just one who is much more moderate and balanced in her beliefs—and she’ll pick up her grandma on Sunday mornings and take her to church and to lunch afterwards. She will also still be friends with Zo but will have an extended circle of friends as well.

Chapter 16: I love the role of music in Zo’s life. What do you think the first five songs on Zo’s latest playlist would be?

Watts: Well, in the book, Zo listens exclusively to David Bowie, and I think Bowie is still a huge part of hir life and that his final album is very important to her. But ze also has high hopes for the new Freddie Mercury biopic and so has been listening to Queen a lot. With Claire’s influence, Zo has been listening to more contemporary artists, especially artists who explore gender and sexuality (and of course, give props to Bowie). The last title on hir list is by a Knoxville band Zo tries to catch when they play locally—the Pinklets, who are all teen girls and who rock.

The albums on Zo’s playlist: Blackstar by David Bowie, Sheer Heart Attack by Queen, Masseduction by St. Vincent, Dirty Computer by Janelle Monáe, and The Pinklets by The Pinklets.

[This article originally appeared on 10/23/2018.]

Julie Danielson, a former school librarian, blogs at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast and writes about picture books for Kirkus Reviews, BookPage, and the Horn Book. Her first book, Wild Things! Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, is now out in paperback.