Memory and Forgetting

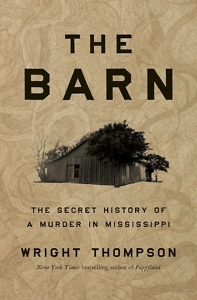

Wright Thompson’s The Barn reckons anew with the infamous murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till

Wright Thompson’s latest book, The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi, revisits what is often considered the most galvanizing event of the civil rights era: the 1955 murder and mutilation of 14-year-old Emmett Till in rural Sunflower County, Mississippi.

Readers may be familiar with the lynching itself, the acquittal of Till’s murderers, and the decision of his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, to display her son’s body at the funeral and in the press. In The Barn, Thompson goes after the circumstances that worked against visibility, illustrating how the Mississippi Delta community “pushed [the murder] almost completely from the local collective memory.”

To understand this erasure, he compiles historical texts, journalism, first-person interviews, and his own relationship to his native Delta, where the titular barn — the site of terrorism and torture — can be seen as “a Rosetta Stone” bringing “erased histories to light.”

One part of his process focuses on key individuals. There’s a saying that white Mississippi is more of a club than a state. In this case, despite the fact that Till’s named killers, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, were considered lower echelon “strivers,” Thompson links their robust genealogies to a mindset of privilege, racial panic, and vigilant, violent self-preservation. Other club members disavowed them, yet they were members nonetheless.

The Barn also describes the Delta’s insular community and the generations defined by land. Thompson crosses the white plantation ecosystem and the Black expatriates to Chicago, making clear that it was not exceptional that Emmett Till would travel from Illinois to visit Mississippi friends and kin, nor was it uncanny that at the murder trial, “eight of the jurors, the lead defense attorney, and the sheriff who drove the acquittal [of Milam and Bryant] were not just from the same place but from the same clan.”

The Barn’s microscope turns telescope when it comes to the global cotton trade and how the Delta stoked fortunes across the country and the world. In contrast to Jim Crow and outmigration to Chicago, Mississippi gentry parlayed their holdings into premiere wealth management (e.g., Charles Merrill of Merrill Lynch) or board seats at the Met. The book covers the history of Delta Pine & Land, a goliath cotton concern that fueled Manchester, England’s conglomerate fiber industry, influenced New Deal policy (reaping ample federal benefits), and was ultimately purchased by Monsanto.

The Barn’s microscope turns telescope when it comes to the global cotton trade and how the Delta stoked fortunes across the country and the world. In contrast to Jim Crow and outmigration to Chicago, Mississippi gentry parlayed their holdings into premiere wealth management (e.g., Charles Merrill of Merrill Lynch) or board seats at the Met. The book covers the history of Delta Pine & Land, a goliath cotton concern that fueled Manchester, England’s conglomerate fiber industry, influenced New Deal policy (reaping ample federal benefits), and was ultimately purchased by Monsanto.

Local, national, and global converge on that nondescript barn. Growing up, neither Thompson nor his peers knew the significance of the place, nor did the man who purchased the land upon which it sat. This isn’t a surprise. One researcher found that Till-related “stories had been torn out of” multiple archival files and that courthouse records contained “not one sheet of paper” about the trial — transcript or otherwise. Boxes of unused history books were locked away from Delta schoolkids who could have learned of the atrocity committed in their backyard.

At times, Thompson’s enthusiasm here feels too ambitious. He strays now and again into tangential Mississippi narratives. They’re compelling, sure, but they can be distracting, especially given the many necessary storylines, facts, persons, and histories.

Yet his personal investment, professionalism, and integrity pay out. This is most evident in the trust he earns from eyewitnesses, including Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., Till’s closest friend in Chicago. The two boys were staying with Wheeler’s family in Mississippi when Emmett was pulled out of bed and kidnapped. As Parker puts it, “Nobody kills like America.”

Somehow, Wheeler Parker still loves Mississippi, and “the pull of home only gets stronger with time.” This, too, establishes a fundamental throughline of the book: resilience and the refusal to keep silent, to give ground. Consumed by trauma and survivor’s guilt, Parker did not have to step in as an activist guardian of Till’s legacy. Another eyewitness, Willie Reed, did not have to testify against the accused — twice — given the mortal threat to himself and his family. The principals, legislators, and investors behind the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner, Mississippi, did not have to spend a decade establishing a museum where “Racial Reconciliation Begins with the Truth.” Hell, nobody had to commission and pay for a 500-pound, AR500 steel historical marker for the boy, after racists kept shooting, throwing acid on, and stealing the ones that proceeded it. Most of all, Mamie Till-Mobley did not have to hold an open casket for her son, whose body sparked international awareness and an era of resistance.

Digging deep into the individual-meets-local-meets-global Mississippi Delta history, The Barn helps reckon with traumatic memory writ large.

Odie Lindsey is the author of the story collection We Come to Our Senses and the novel Some Go Home, both from W.W. Norton. He is writer-in-residence at the Center for Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University.