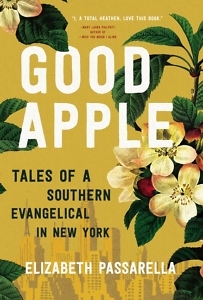

Not as Different as We Think

Elizabeth Passarella on being a “muddled mashup of everything”

Raised in a conservative corner of Memphis, Elizabeth Passarella now makes her home in New York City, and Good Apple: Tales of a Southern Evangelical in New York tells her story: of moving to the city, getting married, becoming a Democrat, and raising a family, all while maintaining her unquenchable Christian faith.

Employing a healthy dose of humor, Passarella has crafted a book that is sure to spark a laugh while cautioning readers against oversimplifying identity. Passarella’s is a passionate voice, never shrinking from the things she is devoted to — her family, her faith, thank-you notes, the city bus, and the crowded apartment she calls home. But hers is also a welcoming voice, and readers will find much to connect with, even if they don’t share her beliefs. Her witty memoir attempts to bridge those gaps that threaten to divide us, insisting that we all have more in common than we may believe. Like a good friend who never fails to shoot straight, Passarella will equally charm and challenge along the way.

Employing a healthy dose of humor, Passarella has crafted a book that is sure to spark a laugh while cautioning readers against oversimplifying identity. Passarella’s is a passionate voice, never shrinking from the things she is devoted to — her family, her faith, thank-you notes, the city bus, and the crowded apartment she calls home. But hers is also a welcoming voice, and readers will find much to connect with, even if they don’t share her beliefs. Her witty memoir attempts to bridge those gaps that threaten to divide us, insisting that we all have more in common than we may believe. Like a good friend who never fails to shoot straight, Passarella will equally charm and challenge along the way.

Elizabeth Passarella answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: In the first line of the book, you humorously list all the ways you might disappoint the people in your life, but you go on to describe a life you’re proud of. How do you walk that tightrope between disappointment and pride?

Elizabeth Passarella: I think it’s important to remember that neither of those things — the disappointing decisions you’ve made or the accomplishments you’re proud of — really matter all that much. Not to get too Jesus-y on you too quickly but, eternally speaking, where I live, what political party I belong to, how big my apartment is (or isn’t), if my kids turn out to be smart or successful… they seem like big deals, but they’re not. I try to remember that my identity is in being an amazing, beloved creation of God, and that will not change if I’m an enormous disappointment to my family — which I’m not, I should add, even though I live in New York, or a perfect mother, which I am also very much not. Disappointing people won’t kill me, and all the pride in the world can’t save me. I have to keep both at arm’s length.

Chapter 16: You call yourself a Southern evangelical, even as you recognize the term has gotten muddy. Why embrace this “radioactive” label? Why is evangelical more accurate than simply Christian?

Chapter 16: You call yourself a Southern evangelical, even as you recognize the term has gotten muddy. Why embrace this “radioactive” label? Why is evangelical more accurate than simply Christian?

Passarella: It may have been an enormous mistake! Only time and book sales will tell! I hope that any barrier to entry the term evangelical may create for some readers is balanced by a curiosity stirred in others, especially since it’s clear that I am also a New Yorker, which many feel is antithetical to being a Christian. I considered putting the term Democrat in the subtitle, too, but I thought people’s heads would explode. That’s kind of the point, though — all of these terms are radioactive to some group, and yet, here I am, being this muddled mashup of everything.

Now, I certainly don’t walk the streets of Manhattan telling everyone I’m an evangelical Christian. I am a member of a Presbyterian church, and I don’t think evangelical is anywhere on the website. That said, as I was writing the introduction and reflecting on the evangelical culture I grew up in, I started digging around for an exact definition of what it truly meant, theologically. And when you strip away the political bedsharing, the tenets are still true for me. I don’t care about the label, but I do have a fairly conservative theology coupled with a liberal political side. I think that’s interesting to people. And I’ve gotten messages from a lot of atheists and Jewish readers who related to the book and enjoyed it, if anyone is on the fence.

Chapter 16: From yelling matches to loving gestures, the particulars of your marriage color this book. This sentence, however, feels universal: “It’s what marriage is, much of the time: choosing, despite the irritating personality flaws, to go on.” Why is it so important to see the “going on” as a choice?

Passarella: A choice is an action. Trust me, my marriage is not going to sail passively through time on the winds of romantic feelings. Not with kids, anyway. We’ve had long stretches of exhaustion, irritation, and apathy. We had to choose to remember our commitment to each other, choose to be patient and kind instead of mean. I like being mean, so it’s harder for me. But fortunately, it’s a loop. When I choose to be nice instead of a monster, my husband responds lovingly, and then I feel more loving, and next thing you know, we’ve stayed happily married for 16 years. Watching Outlander helps.

Chapter 16: What’s your favorite part of parenting in a big city? What about your least favorite?

Passarella: My kids are exposed to everything, good and bad, and I love that. I think sheltering kids is overrated. Walking everywhere and riding public transportation mean they interact with young, old, Black, white, differently abled, non-English speakers, homeless neighbors, and sometimes people who teach them terrible curse words. Occasionally, seeing something ugly or hard (we’ve been flashed more than once) leads to a really great conversation about sin or fairness or mental illness or injustice. I’m not sure I’d be pursuing some of those conversations if it weren’t in my face on the streets of the city, so I’m thankful it is. My least favorite part of parenting here is that people move. It’s a transient city. We have our parenting village like everyone else, but every few years, the village might turn over. I worry my kids won’t have the deep, lifelong friends that I had growing up.

Chapter 16: You write, “We can be proud of where we came from and desperate to escape it at the same time.” Do you have advice for those who feel torn between their past and present?

Passarella: Take the long view. There might be years when you feel very disconnected from where you grew up or even disdainful of it. And maybe that’s what you need to really invest in where you are or find your way. Go for it. But, if my experience is any guide, at some point your present situation will disappoint you or drive you nuts, and you’ll start appreciating your past and longing for it. Try not to be an asshole when you visit home in your 20s and think you’re better than everyone because you moved to a cool city. It’s annoying. Be humble and gentle. It took me a long time to learn that.

Chapter 16: You describe yourself as capable, despite suspecting that self-reliance might keep you from relying more fully on God. I imagine even readers who don’t share your beliefs will sympathize, women who both celebrate “capable” and feel trapped by it. Where do you think this tension comes from?

Passarella: Oh, I love being capable. So, so much. I like being good at things, I like success, and I like being recognized for it. The point I make in the book is that these are all good things. Women should work hard, use their talents, and be proud of their successes. Amen! The problem is when they become ultimate things, which is a term my pastor uses. I feel trapped when my capability is the foundation on which I’m building everything else. Having everything on my shoulders is too big a burden to bear, because what if I drop it? At some point, all of us, even the very strong ones, fail spectacularly or get depressed. So, I have to remember that my ultimate thing is that I’m valued and strong because God loves me. Being capable is a gift I can use and be proud of, but I can also be weak and no less worthy.

Chapter 16: In every chapter, you use stories from your life to build a deeper narrative, one shaped by your faith. At one point, you describe storytelling as a way of “making sense of things that feel too big to just carry around inside our heads all day.” Why are stories so essential to the human experience?

Passarella: Writing, for me, is like talking. In fact, I talk to myself all the time, usually working through a story that I’ll eventually write down — and yes, people catch me telling stories to myself while walking down the street, and yes, wearing a mask for the past year has saved me a lot of embarrassment. I like to compartmentalize, organize, and structure my feelings into stories with beginnings, middles, and ends, because it helps me feel in control of them. Maybe this sounds selfish, but I initially write for myself. What I’ve found throughout my career, though, is that stories make us feel less alone. I’ll write about something absurd that I’ve experienced, that I find funny, in the hopes that it’ll make a reader laugh, and I’ll get an email from a stranger telling me how much she related to it or that she’s been through a similar situation or thought the same awful thought. We need stories to feel less weird. We’re not as different as we think, after all.

[This article originally appeared on February 19, 2021.]

Sara Beth West is a writer and reviewer, usually found at sarabethwest.com. She lives in Chattanooga with her family, dogs, and a cat who always, always, always thinks it is time for dinner.