Obsessed with Understanding

Poet Jenny Qi on what shapes her work

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on February 7, 2022.

***

An accomplished poet and essayist, Jenny Qi brings a complex perspective to her writing. She’s the child of immigrant parents from China, both highly educated, who struggled to make their way in the United States. Qi entered Vanderbilt when she was just 16, and while she thrived there academically, she also had to deal with her mother’s terminal illness, somehow juggling school with trips home to Las Vegas to help provide care, an experience she wrote about for The Atlantic.

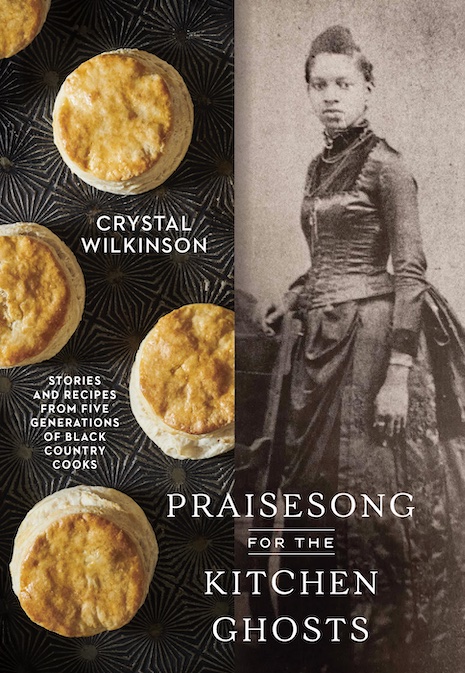

Though Qi was active as a writer during her undergraduate years, studying with Mark Jarman and serving as poetry editor for The Vanderbilt Review, her chief focus was on science. She went on to earn her Ph.D. in biomedical science from the University of California, San Francisco, and it was during graduate school that she began to write intensely, pouring her grief and memories into poetry. Those poems, along with more recent work exploring an array of concerns, are gathered in her award-winning debut collection, Focal Point.

Qi’s essays have appeared in The New York Times and Literary Hub. In addition to writing poetry and essays, she’s currently translating her mother’s memoir of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. She lives in San Francisco, where she works as a consultant, tracking developments in oncology research. She answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: The poems about your parents, and especially about your mother’s death, are deeply personal and revealing. Do you struggle at all with the worry of revealing too much in your work, with telling more of your parents’ story than they might want?

Jenny Qi: Jeffrey Kingman wrote a really kind early review of Focal Point in Compulsive Reader, in which he made a point of distinguishing between the speaker and the author, and I really appreciated that and now try to remind people to keep that in mind. Poetry isn’t exactly nonfiction, after all, and while there are often autobiographical elements, not everything is always 100% true.

Jenny Qi: Jeffrey Kingman wrote a really kind early review of Focal Point in Compulsive Reader, in which he made a point of distinguishing between the speaker and the author, and I really appreciated that and now try to remind people to keep that in mind. Poetry isn’t exactly nonfiction, after all, and while there are often autobiographical elements, not everything is always 100% true.

But to answer your question, yes, I do worry about it, particularly because Chinese culture is one that shies away from ever talking about anything negative or personal. But that’s exactly why I wrote, and I wrote a lot of these poems not with the initial intention of publishing them but rather for myself. I wrote for the younger me who felt so deeply alone in some difficult experiences, and I have to believe that has some kind of value. The other thing I remind myself is that in spite of this aspect of the culture, my mom also wrote deeply personal work, so I hope she would have understood.

Chapter 16: In poems like “The plural of us” and “Two Cures,” you use wordplay as a way into much deeper themes. Is language often the spark for a poem for you?

Qi: Yes, I suppose it is, more than anything else. I love thinking about language, about the various definitions of words across disciplines, the translations of words, homophones and cognates across languages, how adding or removing a single letter can transform a word completely. Often, a poem comes out of ruminating on a word or phrase, and sometimes if I’m obsessing over a word, I look it up in the dictionary, and I start a poem exploring the various official definitions of that word.

The very first poem was actually initially titled “Focal Point” and started with an epigraph containing the various definitions of a focal point. I also studied Spanish for a long time in school, and although I am now very rusty, there are some parts of the Spanish language that I think about a lot and have explored in poems that didn’t make it into this book. Probably the single thing I love the most about Spanish is how there are two ways of saying “to be” based on temporality (ser vs. estar for continuous vs. transient states).

Chapter 16: Focal Point includes some original translations from Chinese, notably a poem by the 11th-century poet Su Shi, and you’re currently working on translations of your mother’s writings. What intrigues you about translation, and what do you find most challenging?

Qi: Honestly, the most difficult thing about translation for me is simply that my Chinese isn’t that good, so it’s very laborious. And there are so many words that don’t quite translate. In poems, in particular, it’s quite challenging to get both the rhythm and meaning right, or at least to a satisfying point, because Chinese is such a concise language with a lot of homophones, and I tend to err on the side of rhythm. But since I like thinking about the quirks of language, these challenges are also what make translation kind of fun for me, particularly on a smaller scale such as with the poems. The biggest pull I feel toward translation work, however, is a need to preserve my familial and cultural history.

Chapter 16: Poems such as “Commonalities,” inspired by the Pulse nightclub shooting, or “About Face,” which deals with anti-Asian racism, are more overtly topical than some of your other work. What pulls you toward those issues? Do you feel a responsibility to take them on?

Qi: When I first started writing poems as a child, it was often in response to events and injustices in the world, and writing a poem or a story was a way to process my emotions around those events. One of my earliest poems, from when I was 12 or so, came from reading an article in National Geographic about sex trafficking and human slavery around the world. I was always kind of obsessed with understanding how we can treat other humans, or any other living things, so terribly and be so shortsighted and how we might evolve beyond that, and I believed that stories could help people recognize our shared humanity. So from a young age, I cared deeply about LGBTQIA rights, gun violence, racism, gender inequality, and environmental instability, and I think once I had processed my personal grief somewhat, it was natural for me to return to those subjects.

Chapter 16: Does your training as a scientist shape your work at all? Do you think it adjusts the lens through which you see yourself and the world around you?

Qi: If you’d asked me this a few years ago, I would have probably said no. But now I realize of course it does. It’s evident in the metaphors and vocabulary I use, the subjects of some of my poems, maybe even the systematic way in which I tend to analyze things. I think a lot about systems, how we as individuals are all part of a system, what roles we play in that system, how much we can or cannot control in that system, how we are all ourselves systems of cells. My scientific background probably has helped me zoom out and recognize connections and patterns, see the forest rather than the trees if you will, though maybe that has also come with age and being less harshly governed by strong emotions. If I pause and consider specific human problems in the context of human history or geologic time or in the context of the larger universe, sometimes it can help temper the existential dread I might otherwise be inclined to feel.

[Read an excerpt from Focal Point here.]

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.