Honoring Grief, History, and Family

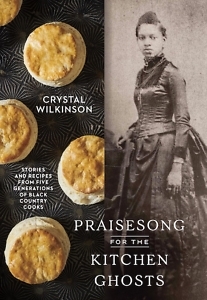

Crystal Wilkinson on her new culinary memoir, Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on January 31, 2024.

***

Hailing from Indian Creek, Kentucky, Crystal Wilkinson is the author of three works of fiction, a collection of poetry, and now, a culinary memoir, Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks. A banquet of voices, memories, imagination, and archival photographs, the new book features dimensions of all Wilkinson’s prior works, each of them rich in sense of place. A former poet laureate of Kentucky, Wilkinson answered questions for Chapter 16 in advance of her visit to Nashville on February 2.

Chapter 16: Tell us the origin story of this project. Had it been percolating for a long time as you worked on other books?

Crystal Wilkinson: The concept of the kitchen ghosts has been with me for a long time and has appeared in both my fiction and poetry before appearing directly in my nonfiction. But this specific book began with an essay that had been commissioned by Seana Quinn, editor of Emergence Magazine. Writer and poet Camille Dungy told Seana about a conversation we’d had about my grandmother and food. Seana asked if I would write an essay about food and my grandmother. I was at Yaddo on a residency when the essay was due, and it came to me in a rush of a few days right before the deadline. The response to the essay was remarkable, with emails pouring in thanking me for the essay and it being shared many times online. A great writer friend and food writer extraordinaire, Ronni Lundy, asked if I was interested in turning it into a book-length project. I initially said no, but the rest is history at this point. I’ve always been interested in the story of my people and their foodways, but I just didn’t expect to write that story myself.

Chapter 16: Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts explores the deep interconnections of food and family, but it is also about food and place, specifically Indian Creek, Kentucky. You write, “Now I realize that the reason we craved blackberries had more to do with homesickness than it did our love for the fruit,” and you’ve written about blackberries before. How do blackberries channel home for you?

Wilkinson: It’s interesting that the other food that serves as a vehicle for home is rhubarb. Somehow it’s not as sexy as blackberries. But I remember when my children were little and telling their friends what we were having for breakfast (rhubarb cooked with sugar over biscuits), they had never heard of it. But blackberries because of the foraging aspect and the tradition of it in my family and all the wonderful dishes that came out of it — blackberry soup over biscuits, cobbler, jam, jelly, jam cake for the holidays — the fruit is a very important part of familial history. Picking blackberries was a joyous occasion but could also be dangerous, and it was something we did as a family — donning long sleeves, long pants, boots in summer to protect us from chiggers, poison ivy, and snakes — and then we enjoyed the riches of the harvest. My grandmother canned them, froze them, we had them fresh. And they were such a big part of our existence and celebration even in winter when my grandmother would make a jam cake or pull a jar to be cooked with sugar to pour over biscuits. Blackberries were a bit of summer that we could have in the midst of winter because of the careful preparation. It’s ancestral. It’s historical. It’s personal.

Chapter 16: One feature of Praisesong that sets it apart from other culinary memoirs is your creation of the character of Grandma Aggy, whose voice joins a chorus of women’s voices. How did you begin to “hear” her voice, and what would you say her sections bring to this book?

Wilkinson: Grandma Aggy represents resilience through slavery and brings the horrible legacy of slavery up close for me and for the reader. I found her in a genealogical search a few years ago while I was in Florida. I couldn’t find much information on her, and I was bereft because I knew why. Because she was enslaved. Because she was a woman. There were few court records, and while her daughter became a famous figure in our hometown, Grandma Aggy was often written into the history books of our town as the slave mother of Patsy Riffe. She haunted me, and it really bothered me that I couldn’t put my finger on her existence beyond her connection with her white common-law husband, beyond her biracial businesswoman daughter. She didn’t exist no matter how hard I searched. But I went to sleep thinking of her and woke up with her voice in my head. Was it spirit? Was it imagination? I’m not sure. Perhaps a combination of both, but she’s been with me since. She is our Grandma Aggy, but she also is an amalgam of women of her time who have never had a voice. It was very important to me to allow her to speak and then in turn to give other women of her time a voice through her.

Wilkinson: Grandma Aggy represents resilience through slavery and brings the horrible legacy of slavery up close for me and for the reader. I found her in a genealogical search a few years ago while I was in Florida. I couldn’t find much information on her, and I was bereft because I knew why. Because she was enslaved. Because she was a woman. There were few court records, and while her daughter became a famous figure in our hometown, Grandma Aggy was often written into the history books of our town as the slave mother of Patsy Riffe. She haunted me, and it really bothered me that I couldn’t put my finger on her existence beyond her connection with her white common-law husband, beyond her biracial businesswoman daughter. She didn’t exist no matter how hard I searched. But I went to sleep thinking of her and woke up with her voice in my head. Was it spirit? Was it imagination? I’m not sure. Perhaps a combination of both, but she’s been with me since. She is our Grandma Aggy, but she also is an amalgam of women of her time who have never had a voice. It was very important to me to allow her to speak and then in turn to give other women of her time a voice through her.

Chapter 16: How did writing this book change you and your relationship to place and family?

Wilkinson: I am forever changed by writing this book. I feel as if it’s been a healing exercise in moving through grief and history and family through food. I have always been someone who honors family, but this has taken my homage deeper. Writing this book has been a personal journey, but the most satisfying part about writing it is that so many people outside of Appalachia have been able to relate to it. I’ve enjoyed so much getting people to write about their own kitchen ghosts and how the act of that and embracing heritage and culture shakes something free in all of us.

Chapter 16: What other Affrilachian works — or creators, or sites — might you say this book is in close conversation with?

Wilkinson: This is a difficult question. I’m not sure it’s in direct conversation with other Affrilachian works. But there is an entire body of work that focuses on African American foodways and Appalachian foodways. Praisesong is hybrid in its approach to craft, so I think it’s in conversation with other culinary memoirs but also with cookbooks and poetic memoirs. I think of writers like Michael Twitty, Jessica B. Harris, Toni Tipton Martin, Ronni Lundy, and of course the great Edna Lewis. But I am also thinking of memoirs and novels that chronicle family life like Lucille Clifton’s Generations, or Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family, or even Kiese Laymon’s Heavy. These are not books about food, but they all take risks in literary form and use lyricism to tell a story about family.

Susannah Felts is a writer based in Nashville. Her writing has appeared in The Best American Science and Nature Writing, Joyland, Oxford American, Guernica, Literary Hub, and elsewhere.