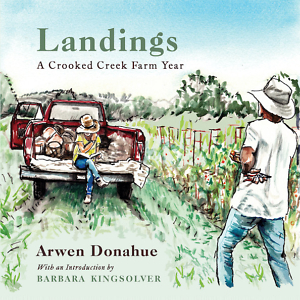

On Modern Farming

Arwen Donahue illustrates daily life on a Kentucky farm

Arwen Donahue married a farmer, David, and spent the past 20 years living on a farm in Kentucky, growing produce to sell to local markets and raising their daughter, Phoebe. In Landings: A Crooked Creek Farm Year, Donahue creates 130 ink-and-watercolor drawings and pairs them with short reflections for each day, providing an intimate glimpse into the life of a modern farmer.

As Donahue notes, many people have a misperception about modern agriculture and farming, believing them to be an outdated romanticization of the past or an industrialized, indifferent behemoth of ceaseless production. For example, in an entry for January 19, Donahue describes her daughter’s struggle to accept the slaughter of one of their steers. Phoebe is “angry, she says, and afraid, and sad. I understand, I tell her. My first introduction to the world of farm animals was through Charlotte’s Web and Watership Down, books in which animals are virtually human, and farmers are among the villains.” Donahue goes on to describe the “economic necessity in nearly all of the decisions we make,” admitting that many of those decisions are not fair, or right, but simply necessary for survival.

Well-known Appalachian writer Barbara Kingsolver celebrates the book for its depiction of “genuine farm life, as lived in the twenty-first century” in her introduction. She continues,

“Unfortunately, it’s the poverty and toil of farming that still holds a sturdy place in many a family’s folklore. Generational memory seems to have fed a modern assumption that manual labor is for the wretched, and farm life is something to be escaped. … It’s a kind of mission work to explain that land itself holds wisdom, and grace comes from reading it every day.”

Donahue admits that she is not the farmer — her husband David is. When David tells her he wants to do the year’s work without the added job of managing interns or other hired help, Donahue worries about the decrease in hands at work, and thus the decrease in production and profit: “I say that it will be too much work for us. ‘It’s always too much work for us,’ [David] says. ‘It doesn’t matter how much help we have.’” Yet when Donahue states that she wants to keep making drawings of the farm, David says, “Do them,” and Donahue is able to balance her freelance work with her farm duties. As she notes, “I may spend the year drawing a slow wave of ruin, but I am curiously happy.” It is this marital balance of pursuing individual passions despite ever-present looming poverty that makes farm life work for the Donahues.

Donahue admits that she is not the farmer — her husband David is. When David tells her he wants to do the year’s work without the added job of managing interns or other hired help, Donahue worries about the decrease in hands at work, and thus the decrease in production and profit: “I say that it will be too much work for us. ‘It’s always too much work for us,’ [David] says. ‘It doesn’t matter how much help we have.’” Yet when Donahue states that she wants to keep making drawings of the farm, David says, “Do them,” and Donahue is able to balance her freelance work with her farm duties. As she notes, “I may spend the year drawing a slow wave of ruin, but I am curiously happy.” It is this marital balance of pursuing individual passions despite ever-present looming poverty that makes farm life work for the Donahues.

Landings, however, is not just a depiction of farming, but of the state of the South. From Donahue’s exceptionally empathetic neighbor who admits to hugging trees and was a vegetarian for years before she realized that eating meat “was a good way to support small local farms” to the librarian at Phoebe’s school who tells Donahue, “I think everyone’s okay, as long as you believe in Jesus,” Donahue describes the polarization between good people and people with good intentions.

When doing tax returns, Donahue reflects on the disparity between strictly economic wealth and the wealth of privilege: “In terms of global history, we are among humanity’s most privileged members.” Donahue’s family owns land, and they make enough food for themselves and for the community. However, she continues, “Our so-called luck is the product of a history of violence. Our ancestors killed or drove off this land’s early inhabitants. Our skin color and sexual orientation provide a kind of cover that gives us a measure of ease in our lives. We quietly accept it, like cash slipped into our palms on the sly.”

Donahue’s transparency and vulnerability in detailing the stresses and the blessings of her life on a farm in Landings help dispel the notion of farmer as villain and farmer as corporation. Instead, modern farmers are everyday people who find pleasure in controlling their own food production and consumption, who enjoy, as Donahue writes, “to eat of the soil of this place, to know that my flesh and this patch of earth are stitched together.” Even more importantly, she asks, “What good is an economy that disregards love?”

Abby N. Lewis is a part-time desk assistant for the North Knoxville Library, an adjunct English instructor at ETSU, and an academic support tutor at Pellissippi State Community College. She is the author of the poetry collection Reticent and the chapbook This Fluid Journey.