Path to the Presidency

Curtis Wilkie talks with Chapter 16 about the invention of the modern presidential campaign

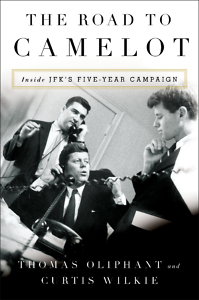

Ever since Theodore H. White’s classic The Making of the President, 1960, journalists and historians have recounted the dramatic election which pitted John F. Kennedy against Richard Nixon. In The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, Thomas Oliphant and Curtis Wilkie focus on JFK’s longer campaign for the presidency, going back to its beginnings in 1956. Full of great details about American political history, the book paints a dramatic, carefully crafted effort to win the Oval Office.

Wilkie, who spent part of his childhood in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was a national correspondent for The Boston Globe and is now the Kelly G. Cook chair in the department of journalism at the University of Mississippi. His books include the memoir, Dixie. In advance of the authors’ joint appearance on October 16 at the new Memphis bookstore, Novel, Wilkie answered questions via email for Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: Why did John F. Kennedy’s presidential bid start in 1956? How did his campaign change American politics?

Curtis Wilkie: Kennedy was ambitious and already beginning to lay the groundwork for a future national campaign when he became caught up in a dramatic contest for the Democratic vice-presidential nomination at the 1956 convention. Though he lost that fight to Sen. Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, he emerged as a rising star in the party and quickly decided to make a run for the presidential nomination in 1960.

To that end, his activities and planning began in the fall of 1956, and Kennedy’s operation became a model for virtually every campaign since then. He started early and established beachheads in key states before his rivals realized what he was doing. He had his own pollster to target travel and primaries. He had talented advisors to help him exploit his advantage on the relatively new medium of television. He used his family’s wealth. Rather than relying on party bosses, he made an end run around the establishment and built grassroots organizations throughout the country that were loyal to him, not the party apparatus. Sound familiar?

Chapter 16: It was a surprise to read how often J.F.K. rejected the advice of his father Joe Kennedy, the wealthy and demanding patriarch. What did this tendency reveal?

Wilkie: It reveals that in the end he trusted his own judgment—and that of his brother Robert, who ran the campaign—rather than his father’s. No question he loved and respected the old man and was glad to spend millions of his money. But he repeatedly ignored his recommendations. Jack Kennedy recognized that his father had made a number of poor decisions when he had served as U.S. ambassador to England at the time of the outbreak of World War II. Jack Kennedy developed his own campaign initiatives and foreign-policy ideas. I think that demonstrated his independence. By 1957, Joe Kennedy admitted it was useless to try to influence his son on foreign policy. “I’ve given up arguing with him,” he said.

Chapter 16: Behind the myth of the glamorous, rational, cool John F. Kennedy, we catch glimpses of a more vulnerable man—a sickly person, a sexually reckless rogue. How, as an author, did you balance the public and private versions of J.F.K.?

Wilkie: My good friend and co-author, Tom Oliphant, and I have covered enough politics to know that you can’t whitewash public figures, even those you might privately like or admire. “Character” had not yet become an issue that reporters wrote about in 1960, but any honest twenty-first-century rendering of J.F.K. requires a “warts-and-all” approach. He and his aides lied repeatedly about his poor health. Tom and I tried not to be too prurient, but Kennedy’s sexual liaisons were reckless, and in some cases dangerous. That couldn’t be ignored in a portrait of the man.

Chapter 16: Was Kennedy’s Catholicism a boon or a detriment? How did his religion shape his bid for the presidency?

Wilkie: At first, Kennedy felt that his Catholicism was a handicap. But on inspection, he saw it as a double-edged sword. As early as 1956, J.F.K.’s close aide Ted Sorensen compiled a report based on data from previous elections showing that Catholicism could be an asset. There were, after all, hundreds of thousands of Catholic voters in big northern states.

Sorensen’s paper was leaked to the press under the name of a prominent Democrat and became widely publicized. J.F.K. wisely determined that he needed to confront the issue head-on, so he talked publicly of his faith rather than hiding it. He reminded audiences that his brother Joe had been killed during World War II. In the face of this sacrifice, he asked, was it fair for Catholicism to disqualify him from seeking the presidency? In the late stages of the race, Kennedy actually benefitted from a bigoted effort by Billy Graham, other leading evangelical ministers, and the Nixon campaign to discredit him because of his alleged loyalty to the Vatican. The Graham-Nixon conspiracy backfired. And after Kennedy’s victory, Catholicism disappeared as a political issue in America.

Chapter 16: By 1960, civil-rights demonstrators were launching sit-ins to protest Jim Crow, yet the Democratic Party’s coalition included both the white “Solid South” and African Americans. Could Kennedy hold both constituencies?

Chapter 16: By 1960, civil-rights demonstrators were launching sit-ins to protest Jim Crow, yet the Democratic Party’s coalition included both the white “Solid South” and African Americans. Could Kennedy hold both constituencies?

Wilkie: He tried. Remember, this was a time when most blacks were unable to vote in the South, and the region was controlled by very conservative Southern Democrats. Because Kennedy got the support of so many Southern delegations at the 1956 convention (they hated Kefauver, whom they considered a liberal turncoat), he thought he could appeal to the South. He courted some leading segregationists: George Wallace and John Patterson in Alabama, James Gray in Georgia, Jim Eastland in Mississippi, and others.

At the same time, he wanted to get an endorsement from Martin Luther King Jr. That wasn’t going to work. After seeing that most of the southern Democrats preferred Lyndon Johnson, J.F.K. turned his attention in early 1960 to winning over African-Americans in the north. His telephone call to express sympathy with Coretta King when her husband was thrown in prison in Georgia late in the fall campaign helped immensely in the general election. The black vote proved to be critical in places like Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Michigan. And because Johnson was his running mate, Kennedy won seven of the old Confederate states, too.

Chapter 16: Television was playing a growing role in electoral politics. How did it help Kennedy triumph over Richard Nixon in the general election?

Wilkie: Television helped him in several ways. Kennedy was naturally telegenic and knew how to use the medium. In the famous first debate with Nixon, J.F.K. looked like he had just stepped out of Brooks Brothers; Nixon appeared to have been sleeping under a bridge for several days. Kennedy also assembled a first-class team of media advisors with backgrounds in television. They not only coached him for the debates but also crafted his commercials. J.F.K. was one of the first candidates to use thirty-second spots instead of long-winded five-minute speeches for commercials.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.