Place Justice

Dr. Enkeshi El-Amin talks with Chapter 16 about nurturing Black-affirming spaces

Dr. Enkeshi El-Amin is a researcher, cultural worker, and lecturer at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where she earned a Ph.D. in sociology. She’s the co-host of the Black in Appalachia podcast and the founder of a non-profit community space known as The Bottom, named for the historic Black neighborhood and business district in Knoxville.

I first got to know Enkeshi in the summer of 2020 to discuss the establishment of a bookstore project as a part of The Bottom. As a bookseller in the region, I was excited to hear about a Black bookselling venture tied to so many important justice initiatives in Knoxville. We’ve been meeting regularly since last fall to talk about all things bookselling and to find ways to collaborate through my role as an event coordinator at Union Ave. Books, among other Appalachian literary projects. Enkeshi and the team at The Bottom have just launched a campaign to buy their own space, so I asked her some questions via email about all the work she’s doing to inspire Black-affirming community in Knoxville.

Chapter 16: First off, I want to hear about your relationship to Knoxville. You came here for a grad school program, not really expecting to be here all that long. It seems like one thing has led to another, and now you are leading all sorts of initiatives in the area. How did you get to know Knoxville?

Dr. Enkeshi El-Amin: I got to know Knoxville through Black people and Black places. Shortly after moving to Knoxville, I started feeling frustrated by the whiteness of this place. I was frustrated on campus. For a long time, I was the only Black woman in my department (among grad students and faculty). I would go to a coffee shop or even the grocery store and not see other Black people. It began to wear on me in ways I can’t even describe. I started seeking out Black people and Black spaces. I started volunteering at the Beck Cultural Exchange Center, and I met several elders there who I’m still in touch with. They helped me to meet other people. I remember being on the committee that planned the first August 8th Emancipation Day celebration. I met one of my good friends there.

My husband worked at Vine Middle school, which is a predominantly Black middle school in Knoxville. I started hanging out there, meeting kids and parents, too. I started going to their Kwanzaa celebrations and community meetings that were held at the school. I found homecoming celebrations for Lonsdale and Mechanicsville and saw Black vendors and kids dancing and local artists performing. It felt familiar. And, of course, I found Knoxville Rescue and Restoration, a group of activists who had been on the ground struggling for the political, economic, health, and education needs of the Black community. With this group of resilient people, I learned about the history of Black Knoxville; I learned the geography of the places; I learned about urban renewal; and I learned that I had something of value to give to my community.

Chapter 16: On to the Black in Appalachia podcast. It’s such an important reframing of this region. Can you tell us about the creation of the podcast? How it formed out of the larger Black in Appalachia research project?

Chapter 16: On to the Black in Appalachia podcast. It’s such an important reframing of this region. Can you tell us about the creation of the podcast? How it formed out of the larger Black in Appalachia research project?

El-Amin: The Black in Appalachia podcast was born out of the Black in Appalachia initiative, which is a multidisciplinary project housed at East Tennessee PBS, working to highlight the history and contributions of Black people in the Mountain South. Chris Smith, our senior producer, learned of a Public Broadcasting podcast training opportunity through Public Radio Exchange (PRX) and approached William Isom, director of the Black in Appalachia initiative, about doing a Black in Appalachia podcast.

William and I had met previously and had talked about doing some collaborative work, but I was still finishing up grad school. Around the time they learned of the podcast training, I had recently completed my Ph.D. and had a little time on my hands. William asked if I was interested in creating a podcast. I agreed to it and together we applied for the program. We were selected as one of six stations to go through the training and the rest is history. But the decision to work on the podcast was informed by the success of the larger project in terms of how well received it was by Black people in the region.

For Black people, whose experiences have been excluded or erased from regional narratives, the Black in Appalachia initiative is very important. We saw the podcast as a way to expand the initiative and were hoping to reach especially younger audiences. Our hopes were that, in creating a space and sense of belonging for young Black people in the region, they might choose to stay in Appalachia. We also wanted other Black people who were still here or who might have left the region but had ties to the region to feel proud and to claim Appalachia as their own.

Chapter 16: So the next project, The Bottom, this whole community space that includes Sew It, Sell It; The Bookshop at The Bottom; and the Community Podcast Studio. What were some of the factors that moved you into holding this type of community space together in Knoxville?

El-Amin: I am a sociologist and cultural worker whose work centers Black Appalachian communities. Over the last five years, my research has focused on Black Knoxville. Themes of Black dispossession and displacement, particularly around urban renewal emerged from my dissertation research and spurred my interest in space reclamation and reimagination work as a form of justice and equity. Additionally, like many Black people in Knoxville, my experiences in this city have been shaped overwhelmingly by being the only Black person in the room in different spaces. The Bottom grew out of the interest I developed from my research as well as these experiences.

The Bottom is an effort to reclaim space for Black Knoxvillians. The space is located on the edge of a Black neighborhood that was destroyed by urban renewal in the 1950s, and its mission is to build community, celebrate culture, and engage the creativity of Black people through curated events, ongoing projects, shared resources, and physical space. At The Bottom, community leaders, activists, artists, cultural workers, university faculty, and others can find a space and opportunities to blend culture, politics, and social history in smart, strategic, and engaging ways in our approach to the challenges facing the Black community in Knoxville.

In addition to the three permanent projects — a bookshop and writing space, a sewing studio equipped with different types of sewing machines and other supplies, and the Community Podcast Studio — as our mission suggests, the work at The Bottom draws heavily on culture and creativity. The Bottom serves as a place where Black people can feel welcome, encouraged, and seen in Knoxville and where their voices and stories can be amplified.

Chapter 16: I’ve heard you mention “place justice” a lot lately. What does that mean to you when it comes to the work The Bottom is doing, and how is that manifested in a city like Knoxville?

El-Amin: The Bottom is named after the first Black neighborhood that was demolished by urban renewal in the 1950s. Unfortunately, it was not the only Black neighborhood to be destroyed by urban renewal; there were two others. Moreover, there were other Black neighborhoods and communities destroyed by other displacement cycles such as College Homes, the housing project that was demolished through the Hope VI program. The Black communities of Knoxville have also lost schools, churches, businesses, night clubs, community centers, and so many other places.

With limited political and economic power, Black places and spaces are vulnerable to place injustice, which is often initiated and facilitated by governing bodies. Given the historical obstacles for Black Knoxvillians to claim space, a collective effort is required to hold Black space in Knoxville and to engage in place-making practices. Recognizing historic and systemic injustices that have directly and indirectly impacted Black people and places is also required to respond and heal from related trauma.

The Bottom proclaims space for Black people to build community, celebrate culture, encourage creativity, and share our history — together! But place justice is not just about acquiring or having Black places; it’s also about thriving in those places. It’s about not being contained but having the freedom to make our places and feel safe wherever we are. It’s about not having to operate in fear inside of those places. It’s also about having our spaces honored and protected. The work we do at The Bottom reflects who we are and what we need to thrive in Knoxville, which is more Black-determined spaces.

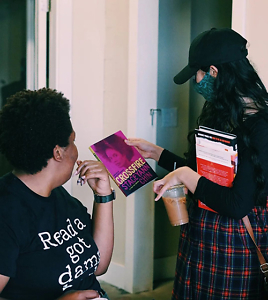

Chapter 16: Since we both work in books, let’s focus in a little bit more about The Bookshop at The Bottom. What are you most excited about in holding space for a Black bookstore in Knoxville? What are some of the programs you have going? I’ve seen the phrase “Black affirming, empowering literature” as a key part of your mission statement. What does that mean to you?

Chapter 16: Since we both work in books, let’s focus in a little bit more about The Bookshop at The Bottom. What are you most excited about in holding space for a Black bookstore in Knoxville? What are some of the programs you have going? I’ve seen the phrase “Black affirming, empowering literature” as a key part of your mission statement. What does that mean to you?

El-Amin: Books are everything, and reading can be so transformative. It feeds our soul in such a special way. I love books, and I believe that bookstores are sacred spaces; especially in Black communities, they often serve as a beacon of hope and regenerative energy. They are meeting places, learning places, caring places, strategizing places, places for activating and reimagining.

Furthermore, I think we are in a moment where non-Black people all over the country are reconciling with and addressing generations of racial inequality. Likewise, we are in a moment where Black people are feeling proud and learning to be unapologetic about their Blackness. For both of these reasons, Black bookstores are crucial in this moment, not only for supplying important and relevant books but for providing a space for communities to talk about and share and process what they read. We are not the only bookstore or place where people can find books in Knoxville, but it is important in this contemporary moment and in this community, where Black people have been excluded, disregarded, and unjustly treated for so many years, that we center and empower Black people and Black experiences in our bookstore. We are excited to do so at The Bottom and to build on the legacy of a Black literary tradition in Knoxville, of Black literary hubs and bookstores that are no longer around today, places like Black World Books and Things and the Literary Imperative.

Chapter 16: So there’s a big move happening! I’m excited that you all have launched the “Give from the Bottom of your Heart Campaign” in order to buy your new community space on Magnolia Ave. Tell us a bit about this big decision to stop renting and own your own space. What does this move mean for the community of The Bottom? I’m struck by the heart-forward approach to all of this; it just feels like you are creating a type of gathering space, a home that goes beyond its programs and missions.

El-Amin: The Bottom is not the first community space of its time to be established by Black people who were responding to a need they perceived in their own community. There were other organizations and spaces before us that were well loved and trying to accomplish similar missions, but those places are no longer here. And part of the reason why they are not is because they did not have full control over their place. They were at the mercy of landlords and others who could make decisions about the use of the spaces they were in without any real considerations for them. We want to interrupt that cycle of displacement that continues to shape the Black community in Knoxville and proclaim loudly that Black place matters. We want to be in full control of our places and hopefully inspire and model for other new Black organizations how to do the same.

There is a lot of redevelopment taking place in the vicinity of The Bottom. We see buildings being sold, torn down, remodeled, and soon construction will begin on new buildings. There are millions of dollars in development coming to our neighborhood. We feel extremely vulnerable by these changes. We anticipate our neighborhood being a hot commodity in the upcoming years and are sure we will no longer be able to afford our rent.

We have put so much work into building what we have. There were no loans or other types of capital invested in building The Bottom. It was me using my salary and other community members giving what they could to get things going. We started out with only 40 books, and we have built, and we have grown, and now we have shelves of books and a very nice-looking space we are proud of. We want our space to be around permanently so that future generations can continue the work we have started.

Chapter 16: Lastly, what are you most excited about as the pandemic subsides? How does The Bottom factor into a post-pandemic Knoxville?

El-Amin: I am excited about having people at The Bottom, doing all the things we intended to do in the space when it was initially conceptualized. The Bottom is here to serve the community in a multitude of uses. Our space may be transformed depending on community needs — we may be a maker workshop, a gathering space, a research lab, a business incubator, a reading room, a knowledge hub, an art gallery, a party space, or a meeting place. We are all of these things and so much more, and we can’t wait for all of the vibrant energy to bust through our doors.

Davis Shoulders is the event coordinator at Union Ave. Books in Knoxville. Davis serves as a series editor for the University Press of Kentucky’s series Appalachian Futures: Black, Native & Queer Voices and is developing a cooperatively owned independent bookstore in Johnson City, Tennessee, called Atlas Books.