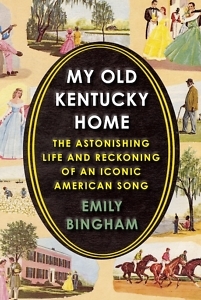

Reckoning as an Act of Love

Emily Bingham exposes the tortuous, white supremacist history behind a familiar song

My Old Kentucky Home: The Astonishing Life and Reckoning of an Iconic American Song, Emily Bingham’s thoughtful, self-aware, intensely moral history of the Stephen Foster ballad, covers a spectacular amount of ground, from the origins of the song before the Civil War up to the present day.

The song, composed in 1853, is probably best known today as the Kentucky state anthem, ritually sung on Kentucky Derby day or at University of Kentucky basketball and football games. The overwhelmingly white patrons who stand and reverently sing the tune at those events likely know little about the song, neither its embeddedness in a larger history of whiteness nor the sundry attempts to reinscribe or reinvent its meaning across time. A meticulous researcher, Bingham convincingly corrects this problem of widespread and willful ignorance — which she admits having shared at one time — while accounting for why and when such mass forgetting happened.

Engrossing twists and turns come with every chapter of the book. How did Stephen Foster, a Pittsburgh native who scarcely visited Kentucky, become its “bard”? The song’s regular use in minstrel shows accounts for some of it. Though it was initially inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Foster ultimately “depoliticized” the lyrics in successive rewrites, so that middle class white women buying sheet music might find it appealing. Unmoored from serious controversy and performed in minstrel shows, the song could cater to both Northern and Southern sensibilities, some with sympathy for the victims of slavery and most in defense of slavery as a presumably benign institution. All such shows appealed to the white taste for racist caricature, whatever the position, whomever the showrunners.

How did Kentucky, a Union state, eventually embrace Confederate plantation mythology? Foster’s song played a role. In a fin de siècle mood of sectional reconciliation between North and South, the song became accompaniment for articles of faith promoted by the Lost Cause cult, including “heritage” organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Bingham plucks some fascinating threads from those years. The Rowan/Frost family in Bardstown, Kentucky, capitalized on the nostalgic mood, embroidering almost entirely from whole cloth a legend that Stephen Foster had penned “My Old Kentucky Home” at their Federal Hill estate.

The Bardstown story only grew more complicated and preposterous, the chicanery and hucksterism piling higher and deeper until Federal Hill ultimately became a Kentucky state park and tourist destination. At every turn, efforts to establish the facts became casualties of needful white myths. Bingham deftly traces lines of descent from state-sponsored campaigns to enshrine Federal Hill as the Old Kentucky Home to the Kentucky Derby, where racist Old South fantasies became a marketing program and Foster’s song emerged as an invented tradition in the 1930s.

The Bardstown story only grew more complicated and preposterous, the chicanery and hucksterism piling higher and deeper until Federal Hill ultimately became a Kentucky state park and tourist destination. At every turn, efforts to establish the facts became casualties of needful white myths. Bingham deftly traces lines of descent from state-sponsored campaigns to enshrine Federal Hill as the Old Kentucky Home to the Kentucky Derby, where racist Old South fantasies became a marketing program and Foster’s song emerged as an invented tradition in the 1930s.

At the broad middle of the 20th century, ignited in no small degree by obsessive promotion from retired pharmaceutical magnate J.K. Lilly, “My Old Kentucky Home” became part of a white American national fantasy, celebrated in Hollywood films, spread abroad with troops during the Second World War, and forming part of postwar Pax Americana proselytizing, especially in the reconstruction of a defeated Japan.

In the civil rights era, segregationists used Foster’s words to encourage massive resistance to integration, policing “racial integrity” against purported communist influences. Eventually, a debate arose over whether Foster’s use of a racist slur in the lyrics should be changed. Those for the change signaled a bland commitment to racial progress at the time, while those against stood for the “tradition.” The complexities only continue closer the present. In sections of the book on the Kentucky Fried Chicken corporation’s uses of the song for Japanese consumers and a state campaign to lure a Toyota factory to the Bluegrass State, Bingham unearths startling and disturbing turns of the historical wheel.

The tremendous range of My Old Kentucky Home might threaten to spin out of control were it not for the clear moral center drawing it all together. Here the stories of attempts by Black people to find some use for Foster’s song across time lend the book needed intricacy. Black singers, performers, composers, and thinkers at times reimagined the tune in response to ever-evolving white needs for the comfort of racial stereotype, making space for it as a means of survival against the threat implied by those needs. Among the more moving attempts at symbolic reversal like this came from Joseph Cotter, whose rewrite of the lyrics celebrated Black progress rather than white fantasy.

Stories like these aid Bingham’s suggestion that when it comes to what should be done with Foster’s song, “[t]he time has come for Black voices to be heard and for white people to be guided by them.” After all, she concludes, “reckoning is an act of love.”

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses related to American culture and thought. He is also a blogger for the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH).