Root, Root, Root for the Home Team

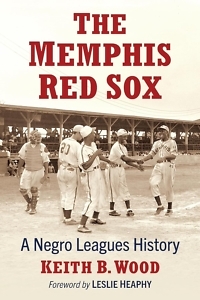

Keith Wood paints a portrait of a Memphis baseball team and the Black community that loved it

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on August 21, 2024.

***

Many years ago, I invited Joe B. Scott, a former star on the Memphis Red Sox, to visit my class on U.S. sports history. In his presence, the students marveled. They relished this living, breathing connection to the bygone Negro Leagues. Mr. Scott passed away in 2013, but his team and era live on in a new book by Keith Wood, The Memphis Red Sox: A Negro Leagues History. Wood recounts not only the on-field action of a franchise that spanned from 1924 to 1959, but also its tradition of Black owners, its centrality to the city’s Black community, and its great heroes, including Joe B. Scott.

Wood is the author of Memphis Hoops: Race and Basketball in the Bluff City, 1968-1997. He earned a Ph.D. in history from the University of Memphis and teaches history at Christian Brothers High School. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Wood is the author of Memphis Hoops: Race and Basketball in the Bluff City, 1968-1997. He earned a Ph.D. in history from the University of Memphis and teaches history at Christian Brothers High School. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: One of the owners of the Memphis Red Sox was J.B. Martin, a figure who looms large in the history of the city. Who was Martin? What did his life and career reveal about Memphis?

Keith Wood: One of four brothers, J.B. Martin was one of the most influential African American leaders in Memphis during the first half of the 20th century. J.B.’s political career points back to his involvement with the Republican Party’s political club, the Lincoln League. As a member of the Lincoln League, he was part of a core group that mobilized the Black community starting in the 1920s. He also was one of the original members of the NAACP branch in Memphis, joining Robert Church Jr. and other prominent Blacks in the city in chartering the first local branch. In addition, Martin helped Church control his political machine within the Black community. This relationship led to political patronage and a sub-post office in his South Memphis Drug Store, a source of pride in the Black community.

J.B. remained the most politically active of the Martin brothers throughout his life. Unfortunately, his political activism came with a price when Boss Crump and his cronies ran him out of town during the 1940 presidential election for supporting Republican Wendell Wilkie over Franklin Roosevelt. Martin’s forced exodus from Memphis reveals the challenges faced by Black political activists who resisted Jim Crow’s constraints in Memphis under Boss Crump. Crump patronized assimilationists, like J.B.’s brother W.S. Martin, superintendent of Collins Chapel Hospital, who followed Crump’s dictates and received funding from the machine. But those who challenged his authority paid dearly.

Chapter 16: A virtue of The Memphis Red Sox is your ambition to recreate the fan’s experience at Martin Stadium, where the team played games. What can you tell us about this experience?

Wood: Martin Stadium was “the place to be seen!” Fans showed up dressed to the nines. Local photographer Ernest Withers would take family photographs before the game, and his wife returned with the developed pictures by the ninth inning. The talent coming through Martin Stadium included Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Turkey Stearnes, Buck O’Neil, and Willie Mays. Opening days became entwined in the community’s social fabric and included a parade from the stadium to Beale Street. The Fourth of July meant a double-header with the overflow crowd sitting along the baselines and in front of the outfield wall.

In 1948, a renovated Martin Stadium opened with state-of-the-art amenities. Along the stadium’s third baseline ran a section of apartments where up to 20 people could live. Modernized concession stands served Memphis-style pork BBQ roasted over the stadium’s barbecue pit. Fans could grab local beers along with that Southern delicacy, chitterlings. The smell of popcorn, Coca-Cola, hot dogs with slaw, and those potent chitterlings filled the air on game days.

Chapter 16: You profile a number of players throughout the team’s history. Can you make any generalizations about their experiences? Were their careers defined by struggle? Joy? Both?

Wood: Buck O’Neil, a Memphis Red Sox legend, told audiences for years, “Don’t worry about ‘Ol Buck, because I was born right on time.” Elected posthumously to the Hall of Fame, O’Neil’s maxim applies to any of the players who donned the flannels for the Red Sox throughout their 37-year existence.

Wood: Buck O’Neil, a Memphis Red Sox legend, told audiences for years, “Don’t worry about ‘Ol Buck, because I was born right on time.” Elected posthumously to the Hall of Fame, O’Neil’s maxim applies to any of the players who donned the flannels for the Red Sox throughout their 37-year existence.

One of the most iconic Red Sox players, Larry “Ironman” Brown, caught more games consecutively than any other catcher on either side of the color line. His prominence earned him multiple starts in the East-West All-Star Game, where he repeatedly garnered more votes than catcher Josh Gibson of the Homestead Grays. Playing in Cuba, Brown cut down Detroit Tigers Hall of Famer Ty Cobb on five consecutive attempts to steal second.

Verdell “Lefty” Mathis, a graduate of Booker T. Washington High School, was one of the best pitchers in the Negro Leagues in the early 1940s. Mathis remains one of only two pitchers with two wins in the East-West All Star Game; the other is Paige. In 1947, Branch Rickey came to Memphis, seeking pitching prospects. The previous season, Mathis underwent surgery for his elbow. Unable to have the operation at the Mayo Clinic because of Jim Crow norms, a white doctor from the Mayo Clinic performed the surgery at Collins Chapel Hospital. Instead of signing Mathis, Rickey signed Dan Bankhead, who became the first Black pitcher with the Dodgers in July 1947. Rickey later told Mathis, “I didn’t act hastily enough. We should have got you before your arm got hurt.”

Chapter 16: Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers is celebrated as a triumph of racial integration, an early harbinger of the Civil Rights Movement. But it had ironic effects, too. What did it mean for the Red Sox and the Negro Leagues?

Wood: As major league baseball began pillaging the Negro Leagues for talent, the level of play began to wane. The Red Sox began bringing in Cuban players to maintain a competitive advantage. Pedro Fomenthal and José Colas became integral pieces in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Larry Brown, now managing, spoke fluent Spanish after years of playing winter ball in Cuba, allowing the Red Sox an advantage with Latino players. They also opened the first baseball training school for Blacks in Greenville, Mississippi, to help identify talent. The Red Sox allowed Robert Boyd to sign with the White Sox. Others found their way to minor leagues throughout organized baseball. Still, the Red Sox ceased operations in 1959. Diminished attendance forced the team to barnstorm for the last few months of the season.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.