Seeing the Extraordinary in the Ordinary

William Eggleston’s photographs illuminate Southern spaces in surprising ways

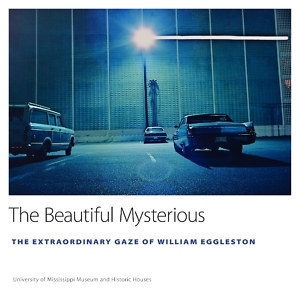

The Beautiful Mysterious: The Extraordinary Gaze of William Eggleston is at least two things at once. Fifty-five photographs from the 1960s through the 1980s, collected and curated by the eminent Southern cultural historian William Ferris, make up the heart of the book. The Beautiful Mysterious also documents a symposium that accompanied an exhibit of those photographs at the University of Mississippi Museum in 2016. The result is a single volume that provides both the stunning photographs and a good deal of context for understanding William Eggleston and his work.

Known as a pioneer of color photography, Eggleston brought techniques formerly used in advertising to the art world, and his work intersects in places with the pop art phenomenon. Eggleston gained wide notice following a much commented upon exhibit of his work at the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1976. This attention came only after Eggleston had worked for some years in relative obscurity, partly owing to his Memphis locale and mostly Southern subject matter. He still resides in Memphis.

Known as a pioneer of color photography, Eggleston brought techniques formerly used in advertising to the art world, and his work intersects in places with the pop art phenomenon. Eggleston gained wide notice following a much commented upon exhibit of his work at the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1976. This attention came only after Eggleston had worked for some years in relative obscurity, partly owing to his Memphis locale and mostly Southern subject matter. He still resides in Memphis.

Commercialism and everyday commodities piqued Eggleston’s interest. An untitled piece from Waterford, Mississippi, in 1983, captures a brown paper sack and a McDonald’s cup in an empty car, viewed from an off-kilter angle through the passenger side door. Sunlight and shadow play and bisect, rendering the top of the bag almost translucent. Feathers and a pine tree air freshener dangle as if from nowhere, creating the impression of a workaday yet strange, hermetic world.

In the same series, the front end of a Chevrolet Monte Carlo pokes in from one side of the frame, interrupting shadows of trees cast across a gravel driveway and the bottom of a porch. Cans, empty plastic bottles, cigarette packs, and other assorted trash lie underneath and on the planked floor at the top of the frame. Cut off at the top, one sees only a foot or so of the scene on the porch: women’s feet in heels, the bottom half of a dog and a purse.

Such whimsy mixes with menace in other instances. The riddle at the bottom of Southern cultural history lies in grotesque juxtapositions between humor and darkness, between storied hospitality and unspeakable violence. In an untitled work from Plains, Georgia, for the 1976 collection Election Eve, what seems to be child’s underwear hangs on a clothesline, slightly out of focus at the far upper left corner of the frame. One’s eyes invariably wander rightward as the focus sharpens to ragged towels hanging on the same line. The towels have holes in them, like eyes cut out for masks, startling in their clarity, yet haunting at the same time.

Eggleston explored moments in a region always in transition. Startling and contemporary even though it is decades removed from us today, the work in this collection refuses nostalgia. The images show a South only recently ravaged by mass consumerism, but the viewer hardly aches for an earlier time. Even Walker Evans’ famous, masterful photos of sharecroppers from the 1930s have, by now, a romance about them that derives from the passage of time. It’s hard to imagine the same fate for the uncanny Eggleston.

His work is unspeakably beautiful but almost always unsettling at the same time. He resembles the recently deceased photographer Robert Frank (The Americans) in this way, but with different technique and subject matter, on the whole sparer and more engrossed with objects than people. That Eggleston made such strange poetry out of ubiquitous objects — trash especially — is nothing short of astounding.

The written portions of The Beautiful Mysterious help place Eggleston in and among other artists — literary, visual, and otherwise. The book includes selected transcripts of the symposium’s roundtable sessions, which offer a good sense of broad themes in Southern history and culture that contributed to the making of the man. One of those eccentric, shy types who appear in Southern bohemian life occasionally, Eggleston has reached something like legendary status in certain circles and underground scenes. His sensibility, where the workaday becomes off-kilter and eventually sublime by means of inventive use of color or angle, has influenced filmmakers such as David Lynch, Gus Van Sant, and Sophia Coppola, among others. Undoubtedly, his influence extends further still. Like the strange persistence of Southern identity, the reasons for influence like his can be difficult to pin down. It’s mysterious. Its traces — and thus its truth — are indelible once you’ve seen them.

Peter Kuryla is an associate professor of history at Belmont University in Nashville, where he teaches a variety of courses concerning American culture and thought. He also blogs for the Society for U.S. Intellectual History (S-USIH).