She Had a Dream

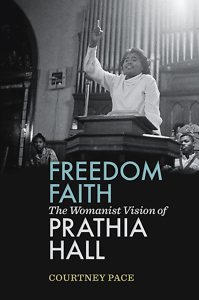

Freedom Faith examines the little-known influence of civil rights leader Prathia Hall

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on January 10, 2020.

***

Recording artist Brian Eno once toured a sprawling Russian art exhibit that made him uniquely aware of all the little-known painters who coexisted with the alleged immortals. Every genius, he noted, worked within a scene of thoughtful people cultivating, through the expenditure of their own creative resources, a new world of possibility. Eno gave the phenomenon a name: scenius. “…[G]enius is the talent of an individual, scenius is the talent of a whole community,” he said in a 2015 lecture. There is no genius, we might say, without a scenius.

In Freedom Faith: The Womanist Vision of Prathia Hall, Courtney Pace invites us to dwell within a similar concept regarding a figure whose gift of insight has functioned as a rhetorical touchstone against racism for over half a century. For many within the scenius that came to be called the civil rights movement, Hall’s claim to fame has long been the fact that Martin Luther King Jr. borrowed (with her permission) the line, “I have a dream,” after hearing her speak it aloud repeatedly at a prayer meeting in Albany, Georgia, in 1962.

In Freedom Faith: The Womanist Vision of Prathia Hall, Courtney Pace invites us to dwell within a similar concept regarding a figure whose gift of insight has functioned as a rhetorical touchstone against racism for over half a century. For many within the scenius that came to be called the civil rights movement, Hall’s claim to fame has long been the fact that Martin Luther King Jr. borrowed (with her permission) the line, “I have a dream,” after hearing her speak it aloud repeatedly at a prayer meeting in Albany, Georgia, in 1962.

But as Pace reminds us, this bit of trivia is only useful insofar as it serves as a compelling entry point for taking fuller measure of Hall’s witness as a minister, activist, and academic. Hall’s vision of “freedom faith,” Pace contends, helped dissolve the popular division of religion and politics for generations of leaders and laborers in the struggle for equality and human rights.

Pace gets right to it in showing us why Hall was a presence to reckon with, and in doing so she illuminates neglected tensions among the thousands of Americans who risked life and limb in acts of nonviolent resistance to white supremacy during the late 1950s and early 1960s. For instance, footage of the trampling, tear gassing, and torturous beating ordered by Sheriff Jim Clark against marchers in Selma on Bloody Sunday in 1965 is well known, but Pace gives us Prathia Hall’s account of the immediate aftermath. Hall recalls the scene that day in Selma’s Brown Chapel, which had been converted into an impromptu refuge and hospital. Fearing that some marchers, bleeding and brutalized, might be tempted to seek violent retribution against white people in Selma, one member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference tried to lead the injured in song, singing the words, “I love Jim Clark,” and insisting that failure to do so sincerely meant that they wouldn’t see Jesus upon dying.

Hall was incensed by this and said so. She called it an instance of “spiritual extortion” and “an abuse of people’s faith.” By her lights, freedom faith isn’t a denial of legitimate rage but a transformation of fear into courage. Against oversimplification or the spiritualizing away of real grievances in the struggle for justice, Hall saw every encounter as an opportunity for “mutual educational exchange” and the life of freedom faith as one in which people “live in an oppressively crushing system without being crushed.” Having suffered incarceration and been shot at under a violent regime sustained by people who claimed Christianity, she was well studied in the fact that misconceptions of God, love, and forgiveness serve to justify a wide array of brutality.

Hall was incensed by this and said so. She called it an instance of “spiritual extortion” and “an abuse of people’s faith.” By her lights, freedom faith isn’t a denial of legitimate rage but a transformation of fear into courage. Against oversimplification or the spiritualizing away of real grievances in the struggle for justice, Hall saw every encounter as an opportunity for “mutual educational exchange” and the life of freedom faith as one in which people “live in an oppressively crushing system without being crushed.” Having suffered incarceration and been shot at under a violent regime sustained by people who claimed Christianity, she was well studied in the fact that misconceptions of God, love, and forgiveness serve to justify a wide array of brutality.

For Hall, that brutality was also evident among leaders of her own church who denied her call to ministry: “The same God who made me a preacher is the same God who made me a woman. And I am convinced that God was not confused on either count.” Her path to becoming the first female Baptist minister in Philadelphia was hard won, as she was often caught between an abusive husband at home and a culture that rejected her vocation as unbiblical. But in this, she located herself along a trajectory of women who have sustained church life for centuries despite marginalization: “Many women are being battered from the pulpit for their faithfulness to the church.”

For this sin of oppression, she called upon male leadership to repent, and many did. This was the fruit of her commitment to a tradition she refused to quit. “The Baptist church is going to have to deal with me,” she insisted in 1997. “Some of us have to remain in the recalcitrant church. Everything we know about God is that the living God is not a bigot.”

Pace, a professor of church history at Memphis Theological Seminary, places Prathia Hall among a pantheon of elders, alongside her friend Jeremiah Wright (who officiated the marriage ceremony of Barack and Michele Obama but was later disavowed by the president for denouncing the United States government) and Congressman John Lewis, who describes Hall as “one of the founding mothers of the new America.” In an age when appeals to generalized faith often serve moral unaccountability in our everyday politics, it’s encouraging to imagine that Prathia Hall’s commitment to freedom faith might yet again serve as a righteous example.

David Dark is the author of five books, including The Possibility of America, Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious, and The Sacredness of Questioning Everything. He lives in Nashville and teaches at Belmont University and the Tennessee Prison for Women.