Smart, Sad, Funny

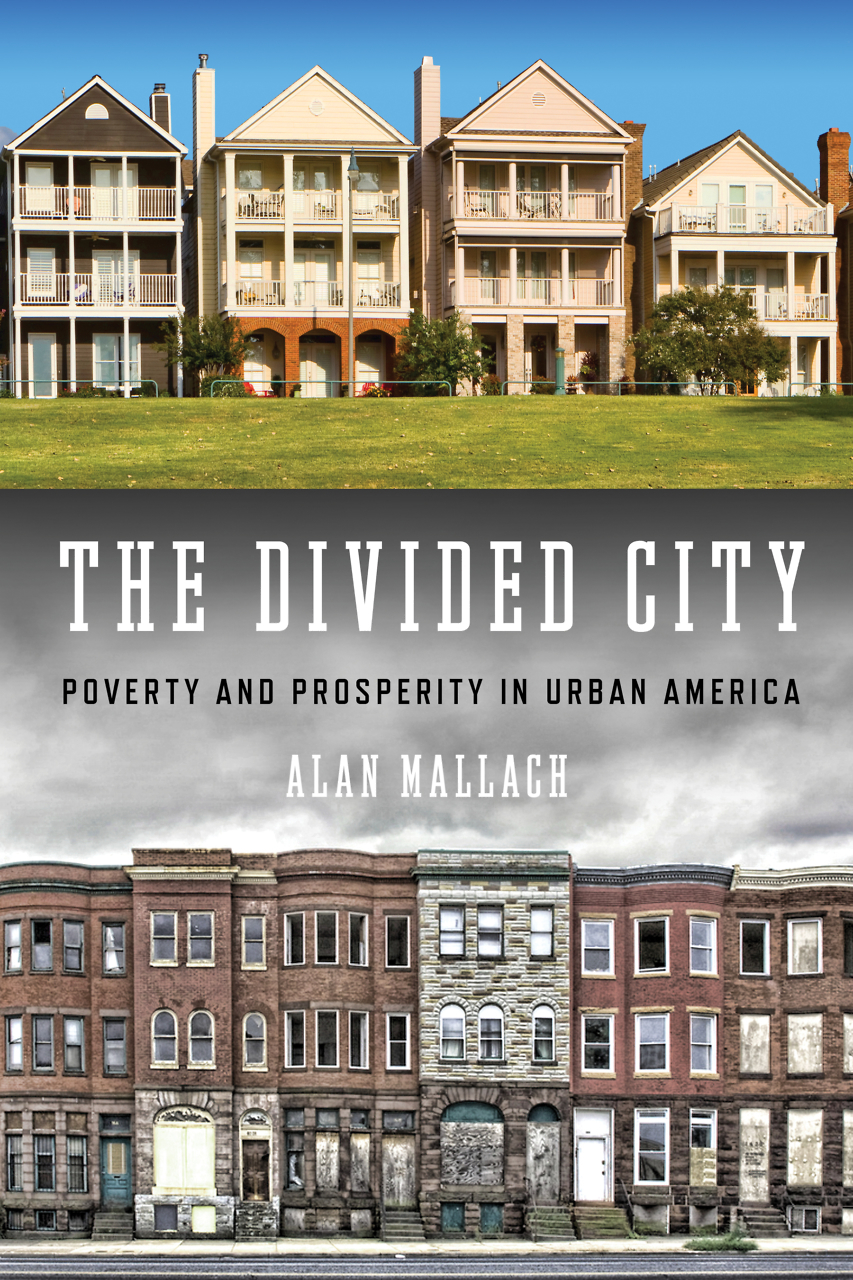

Poet Mary Jo Salter’s new collection, Nothing by Design, is heavy and light by turns

Mary Jo Salter has said that it’s “a hard balance” to write poetry that explores intellectual concerns yet still sounds “like a human being wrote it.” She is a master of that balance in her own work, and her new book, Nothing by Design, is no exception. The poems in this varied collection, ranging from comical haiku to bittersweet remembrances of dead friends, display Salter’s characteristic wit, erudition, and formal grace, along with real depth of feeling. They are entertaining in the truest sense, speaking to the reader’s mind and heart with equal urgency, and they have a bit of smart silliness thrown in for good measure.

The collection is something of a hodgepodge, with no obvious overarching concept, but the poems have been gathered into loosely connected groups that share certain elements. The opening section, for example, is called “The Numbers” and includes a lighthearted tribute to Richard Wilbur on the fiftieth anniversary of his book The Beautiful Changes, a poem called “Fractal,” which meditates on that mathematical concept as embodied in a school of fish, and “Common Room, 1970,” a devastating commentary on fate, rendered via a portrait of young men watching the Vietnam-era draft lottery:

The collection is something of a hodgepodge, with no obvious overarching concept, but the poems have been gathered into loosely connected groups that share certain elements. The opening section, for example, is called “The Numbers” and includes a lighthearted tribute to Richard Wilbur on the fiftieth anniversary of his book The Beautiful Changes, a poem called “Fractal,” which meditates on that mathematical concept as embodied in a school of fish, and “Common Room, 1970,” a devastating commentary on fate, rendered via a portrait of young men watching the Vietnam-era draft lottery:

[…] He heard the number whiz,

then lodge safe as a bullet in his brain.

Like a bullet in a dream: you’re dead, you’re fine.

No need to wish for C.O. or 4-F.

Oh thank you, Jesus God. No Nam for him.

Salter swings easily between seriousness and whimsy, and Nothing by Design has a sizable section called “Lightweights” devoted to funny—often bitingly funny—poems. These include a bit of everything, from very twenty-first-century haiku (“Leash dog, strap iPod / to bicep; jog, shower, dress— / it’s not worth the time”) to a set of riddles about musical instruments. Salter pokes fun at the literary life, too, most cleverly in “Edna St. Vincent, M.F.A.”:

Her classmates listened, bored, without a clue.

Still, they like her, partly because she friended

everybody who asked, and fucked them, too.

What might be the funniest poem in the book, however, is tucked into “The Afterlife,” a section devoted to the generally unfunny subject of dying. “Over and Out” is the wry monologue of a pilot informing his passengers that their plane is about to crash. For anyone who has ever been irked by the overly cute patter of a Southwest flight attendant, Salter offers a reminder that it could be worse: “Let’s be frank. This flight is headed for / your longest vacation. Tonight, the only gates / we’ll taxi to are pearly.” Salter’s other considerations of death are considerably more somber. The section’s title poem muses on the Egyptian funerary figurines called shabti, which were intended to work for the deceased in the afterlife. “Hard to Say” and “Cities in the Sky” are about encounters with the dying. All these poems are examples of Salter at her insightful and accessible best, especially “Hard to Say,” in which an elderly woman’s capacity for speech is withering away: “Things are either ‘terrible’ or ‘amazing.’ / Nothing is in the middle. It’s the ending.”

What might be the funniest poem in the book, however, is tucked into “The Afterlife,” a section devoted to the generally unfunny subject of dying. “Over and Out” is the wry monologue of a pilot informing his passengers that their plane is about to crash. For anyone who has ever been irked by the overly cute patter of a Southwest flight attendant, Salter offers a reminder that it could be worse: “Let’s be frank. This flight is headed for / your longest vacation. Tonight, the only gates / we’ll taxi to are pearly.” Salter’s other considerations of death are considerably more somber. The section’s title poem muses on the Egyptian funerary figurines called shabti, which were intended to work for the deceased in the afterlife. “Hard to Say” and “Cities in the Sky” are about encounters with the dying. All these poems are examples of Salter at her insightful and accessible best, especially “Hard to Say,” in which an elderly woman’s capacity for speech is withering away: “Things are either ‘terrible’ or ‘amazing.’ / Nothing is in the middle. It’s the ending.”

Many of the poems in Nothing by Design touch on death of one sort or another, and if this polymorphous collection has a central concern, it is loss and our helplessness in the face of it. There is a group of poems about divorce (“Bed of Letters”), a translation of the mournful Old English poem “The Seafarer,” and two long, beautiful elegies, of a sort, about extraordinary poets Salter knew: Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky, who died in 1996, and Amy Clampitt, who published her first poetry collection in 1983, when she was sixty-three years old, and won wide acclaim for her work prior to her death in 1994. In all these poems Salter considers our complicated relationship with relics, and the Clampitt poem, “Unbroken Music,” is a particularly rich exploration of their essential paradox, being both precious and ultimately worthless because “in time everything / we save will be lost.”

Even the book’s title (which is taken from a villanelle called “Complaint for Absolute Divorce”) could be read as a reference to the essentially incomprehensible, random nature of our losses. But Salter seems, finally, inclined to look for a way to transcend the randomness (or what she, quoting Clampitt, calls “the coincidence factory”). In the collection’s final poem, “Lost Originals,” she finds a kind of redemption in the relentless creative passion of William Blake, and in the last stanza of “Unbroken Music,” having put away both relic and memory, she sees a possibility of honoring her friend through “the fierce desire to live my own days.”

Mary Jo Salter will discuss Nothing By Design at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13, 2013. All festival events are free and open to the public.