So Many Stories to Be Told

Ruta Sepetys on her passion for sharing underrepresented history

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This interview originally appeared on January 31, 2022.

***

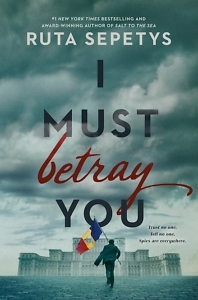

Nashville resident Ruta Sepetys has been a mainstay in young adult literature since 2011, when Between Shades of Gray changed so much about how we view historical fiction and YA. With her latest, I Must Betray You, award-winning Sepetys returns to the difficult task of telling an unfamiliar story from history, one that deserves a much wider awareness. Thanks to Sepetys’ careful research and respectful approach, the people living under the Ceaușescu regime in Romania in the late 1980s are brought to life, most notably the protagonist Cristian.

Cristian is a teenager, living in a small apartment in Bucharest with his parents, his sister, and his grandfather (Bunu). The regime limits everything: access to information, food, electricity, and even their ability to trust one another. Never knowing who might be an informer to the Securitate officers, Cristian and everyone around him live in fear and mistrust. But Cristian is a writer, and even as he finds himself entangled in a web of complications and deceit, he believes he has the ability to help, to make a difference through his words.

Ruta Sepetys spoke with Chapter 16 by phone in early December. Our conversation covered a lot of ground, starting with the weather before quickly getting into the ways we are all shared recipients of and participants in history. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Chapter 16: One of the things that’s so unsettling for those of us here in Tennessee is how warm it has been. We’ve got the decorations up, we’re doing the holiday preparations, the kids are heading into exams, but it’s hard to believe it’s really December.

Ruta Sepetys: Yes, I agree! It is a psychological disruption where things we’ve previously been able to count on, like the seasons and weather, even that has been disrupted. As someone who’s fascinated with history, I can’t help but think about how today’s kids are the true witnesses, and one day, someone will be coming to them and asking, “What was it like?”

We’re living through history. I try to remind myself of that, to make notes and keep a journal, because in my work, I rely on these pieces. To read daily journals of people allows me to know what they were experiencing and thinking at that time. So I keep my journal in the hopes that it might be informative to someone writing about the pandemic.

Chapter 16: Speaking of history, your latest novel, I Must Betray You, has been described as a “historical thriller,” and your books are often noted to be “crossover novels,” enjoyed by teens and adults alike. How do you feel about these labels? Of course, you likely have little input on how your books are marketed, but I’m curious about whether you feel like this sorting and grouping is primarily a good thing, or if there’s something else there that might be more complicated.

Sepetys: It’s true that in most cases, authors don’t control how the book is marketed or labeled, and because I’m writing about underrepresented history, I don’t pay much attention to the label that a bookseller or publisher chooses. What I want is to reach the largest audience possible — not in an effort to sell books or make money — but to share this underrepresented history and give voice to the people who experienced it.

Sepetys: It’s true that in most cases, authors don’t control how the book is marketed or labeled, and because I’m writing about underrepresented history, I don’t pay much attention to the label that a bookseller or publisher chooses. What I want is to reach the largest audience possible — not in an effort to sell books or make money — but to share this underrepresented history and give voice to the people who experienced it.

So if I Must Betray You is labeled for teens as a historical thriller, if that means that it might draw more teens to read the book, I’d be delighted about that. And ultimately, it’s up to the reader to determine the value of the story, not for the author to explain it. If a label pulls someone in, then great! They will determine the value and interpret the story on their own. We can use my first novel as an example. Between Shades of Gray came out when Fifty Shades of Grey came out, and I had a lot of readers who bought my book thinking they were getting entirely another story! To this day, some of those readers who discovered my book by accident are still my readers!

Chapter 16: That’s so interesting because I often think about it in the reverse, worrying about those readers who wouldn’t read your book because they thought it inappropriate or illicit. To see it from that positive perspective is much better!

Sepetys: It’s true! Perhaps they thought they were going in for one type of story, and then Lithuania never looked so sexy! But ultimately, I’m so desperate for people to find these stories because so often, we don’t even know what happened at that time or in that place. However readers get to the work is fine by me. As long as it doesn’t exclude any possible reader.

Chapter 16: You’re published as a YA author, but there are plenty of people in their 40s, like myself, who lived through this era in the United States and would appreciate connecting the dots between the big pop culture moments that we knew about, like the fall of the Berlin Wall, and this story of the people of Romania. The biggest hope is that the story would be heard, right?

Sepetys: Oh absolutely, and it’s interesting because more than a decade ago, when my agent was shopping Between Shades of Gray, I got a large stack of rejection letters, most of which indicated that historical fiction didn’t sell. It was a difficult genre for YA or adult readers, apparently. But that’s changed so much now. Also, in about half the countries I’m published in, I’m not a young adult author; my books are marketed for adults exclusively. And then in France, I’m only a young adult author. It’s fascinating!

Chapter 16: It is. Either way, what you’re doing is in contrast to what Bunu says of Cristian’s father: “You’ve become a man without a voice.” In this book and in others, you seem to be able to give those characters a voice.

Sepetys: Well, I’m hesitant to agree because I’m writing about time periods that I didn’t experience myself, and that question looms: What right do we have to history other than our own? I try to approach every story, every book, every research interview with reverence. So I hesitate, but I want their stories to speak. I want their humanity, their endurance, that force of life and power of love, to speak. The atmosphere was so repressive, yet these human beings endured. They found light where there was none; they formed relationships and fell in love. I want that to speak in hopes that people will say, “I want to know more” and do the research, and then they will find the sources, the Romanians who have written about this and so beautifully.

Sepetys: Well, I’m hesitant to agree because I’m writing about time periods that I didn’t experience myself, and that question looms: What right do we have to history other than our own? I try to approach every story, every book, every research interview with reverence. So I hesitate, but I want their stories to speak. I want their humanity, their endurance, that force of life and power of love, to speak. The atmosphere was so repressive, yet these human beings endured. They found light where there was none; they formed relationships and fell in love. I want that to speak in hopes that people will say, “I want to know more” and do the research, and then they will find the sources, the Romanians who have written about this and so beautifully.

Chapter 16: Yes — that’s exactly it! You do such comprehensive and thoughtful research and interviews that the stories are their voice. It isn’t you claiming their stories, but perhaps you’re a conduit for their stories?

Sepetys: It’s true! Whenever I speak with students, they’ll say, “Wait. To write historical fiction you have to do research?” It sounds so terrible to them! But change the word research to investigation and think of being able to sit down with a true witness. It’s in those interviews that the characters come to life. I will pull threads from 10 different people and braid them together to create one composite character. As a result, I’m able to represent a larger human experience, and maybe there are more Romanians who say, “I relate to that!” So that’s definitely part of the process, trying to be a conduit and facilitator of their experiences.

Chapter 16: In those interviews, were there stories that stand out that you didn’t braid into your characters’ lives?

Sepetys: Yes. There are some stories that would be great if I were writing straight fiction, but I hold myself accountable and ask, does this element serve the story or serve the history? I want to be as authentic as I can without info dumps, and there were some really great personal stories, but they were so unique that they would have been perfect for a memoir about this person’s life. And then there were multiple stories that contained such graphic brutality, such human rights abuses, that I had to find a way to create the atmosphere of oppression, so readers would feel this world of enforced obedience, without putting those stories in the book.

So yes, there are many stories to be told, and how I tell those stories will also determine the audience that I’m able to reach. Certainly, the last thing I want to do — that I refuse to do — is to talk down to my readers. Young people are way savvier than I am, and they’re going to smell if I’m trying to clean this up in a condescending way, but I do challenge myself to express it in the most accessible way. And then, too, there were those who said, “I desperately want to tell you this story, but you have to promise me that you will never ever put it in the book.” And I made that promise. I appreciated that willingness to share, their desire to give me a perspective that would help me know how it was — but they were insistent that I not use the story.

Chapter 16: But it seats you in the reality, it informs your ability to tell the story, if you have more of the context, even if you couldn’t use it directly. And that comes through — that sense of understanding is on display in the book.

Sepetys: Well, that’s probably the greatest compliment you could ever give me. I want the reader to think, “What would it be like to be the villain? To be Securitate, one of these agents? Imagine that.” And then also, the people who acted once the revolution began. For example, the gentleman I interviewed who was on the firing squad, the team who executed the Ceaușescus — the first thing he said when he sat down was, “You need to understand: A revolution eats its heroes.” Things are perceived one way, and then with the buffer of time, people can change their minds, and a hero can become a villain. It’s so complex. I want to present that complexity in a way that’s not complex, if that makes sense.

Chapter 16: It does. It reminds me of Solzhenitsyn’s comment in The Gulag Archipelago about the line of good and evil running down the center of every human. That idea that we all hold within us the ability to be one and the other — it’s complex, yes, but like you say, it is a simplification since it’s universal.

Sepetys: Yes! I love that you brought up that example because it really does encapsulate what these periods of history are like. And of course, time is the unveiler of truth. People working in Washington, D.C., saw Ceaușescu in one way at that time, and now they are shocked to recall the pictures of Ceaușescu on office walls throughout D.C. He was a maverick. He was independent, somewhat, from the Soviet Union, and then, how it changed. It takes time.

Sepetys: Yes! I love that you brought up that example because it really does encapsulate what these periods of history are like. And of course, time is the unveiler of truth. People working in Washington, D.C., saw Ceaușescu in one way at that time, and now they are shocked to recall the pictures of Ceaușescu on office walls throughout D.C. He was a maverick. He was independent, somewhat, from the Soviet Union, and then, how it changed. It takes time.

Chapter 16: Time, yes, and transparency. We could have all of time, but if we don’t tell these stories, if we never hear them, it doesn’t change anything. So I have to commend you for doing the work of bringing these stories into the light, sharing the stories of those who lived through it, and hoping that we all continue to learn more about ourselves along the way.

Sepetys: It’s so sensitive of you to mention transparency because the Romanian population, even after Ceaușescu was executed, they didn’t have transparency. The Securitate files were not opened. A replacement set of Communists took over, and these young people — high school and college students who had literally fought in the streets with their bare hands — they still didn’t know what really happened. They thought it was a revolution, but to not have that transparency had to be so painful, and I imagine it made them feel so helpless.

Chapter 16: We often think of history as having these tidy narratives, don’t we? Like, the Berlin Wall fell, the revolution occurred, everything changed afterwards, and it did! But as you note, it didn’t always. It’s fascinating. Also fascinating is your protagonist, Cristian. He has to grope his way toward understanding himself as a writer, gradually giving himself permission to embrace this identity. Of course, some of that for him is contextual — the realities of living in an oppressive dictatorship — but some of that is real for every writer, right? Did any part of his process resonate with your path to becoming a writer?

Sepetys: Oh, that’s a lovely question! Yes. Of course, I didn’t face the hurdles that Cristian did, living literally in a closet, in the dark. But I do feel that writing, or any creative endeavor, requires courage — and many forms of courage: creative courage, courage to fail, courage to share yourself, to open yourself up.

I had a unique path to becoming a writer in that I spent over 20 years working in the music industry first. I was living in Los Angeles, representing songwriters and bands and film composers and producers, and I had this front row seat to creativity where I learned that if and when we do put in a piece of our own selves — our passions, our feelings, our thoughts — the result has way more resonance. Learning that over the years did help develop my own voice.

When I first decided to write, I was working on a middle-grade mystery, and I was excited about it, but I wasn’t passionate about it. And it was only when I started writing what I was passionate about that I started getting the attention of agents and editors in earnest. But it does take self-exploration and meetings in the mirror, and you have to ask “What is the price of admission?” Which is something that Cristian has to ask. He wants this, but what is the price?

So yes, I definitely see a correlation, and it’s why I feel so fortunate to work with young people. Young people are tremendous writers, because they are such deep feelers. They are courageous to put those feelings on the page. That’s what I try to think when I have a main character who is a teenager. I try to think: What would they really say? And then, how would they really put it on the page? Or what are they feeling that they aren’t expressing, that they can’t put on the page?

Chapter 16: Definitely. When you are passionate about the story or the art, you are putting a part of yourself out into the world, and the world might say no. So that willingness to be vulnerable is a huge part of it, and how brave Cristian had to be to be doubly vulnerable — to put his writing into the world and know that it might risk his very life?

Sepetys: Absolutely. And young people can be so inspired by older people, a different generation. In this case, it was his grandfather, and in many cases, when I interview Romanians who were young poets or writers, they were inspired by authors whose books were banned, and it gave them such courage. If someone else can say and feel these things and be honest about it, then maybe it’s ok for me to be honest and vulnerable.

Sepetys: Absolutely. And young people can be so inspired by older people, a different generation. In this case, it was his grandfather, and in many cases, when I interview Romanians who were young poets or writers, they were inspired by authors whose books were banned, and it gave them such courage. If someone else can say and feel these things and be honest about it, then maybe it’s ok for me to be honest and vulnerable.

Chapter 16: And it’s not always the dramatic story that is the inspiration. I’m thinking of the way Cristian and Bunu would connect through humor. Cristian explains, “Joking about the regime was illegal and could ferry you straight to Securitate headquarters. But people told jokes anyway. In a country with no freedom of speech, each joke felt like a tiny revolution.” Do you think these tiny revolutions contributed to the larger revolution in the end?

Sepetys: Yes! When Cristian tells Bunu that he’s heard a joke on the street, that the Bibles were all turned into toilet paper, for example, it was a way to relay information under the protection of the joke. It was important for me to include that element because whenever I interview for a project, there are common threads that come up all over the country, and that was one — about the jokes. It was a coping mechanism for some people, and literally something to make them smile when there was nothing to smile about. But it was also a way to relay secret information.

Chapter 16: And humor is a great universalizer! We don’t have to speak the same language or share the same cultural experiences to find the same things funny. When we laugh, we don’t sound different for the most part. There’s a humanizing aspect to humor, and that was critical at the time. If you felt so unseen, not allowed to be an individual, how important it must have been to still be able to laugh.

Sepetys: And laughing is a form of sharing. Under these circumstances, they couldn’t share anything. They didn’t know if the walls or the light fixture was listening or who was on the other end of that listening device. But a laugh! There were a lot of things they could steal from them, but they couldn’t steal that spirit, and that laughter was something they could share with other people in an atmosphere where it was frightening to share things.

Chapter 16: The title makes clear that issues of trust and betrayal are prominent in this historical retelling. Though undoubtedly a very real part of Romania in the 1980s, after reading this passage, I couldn’t help but see parallels to contemporary America: “Mistrust is a form of terror. The regime pits us against one another. We can’t join together in solidarity because we never know whom we can trust or who might be an informer.” In what ways do you see this kind of mistrust today? And are there lessons we could learn from the people of Romania?

Sepetys: I have seen these overlaps with every historical novel that I’ve written. It’s chilling because we want to progress, and we want to learn and grow and create hope for a more just future. But knowledge of history gives us perspective to the present. There are echoes, but there always are. It doesn’t matter what country or what history. I think that phrase ‘history repeats itself’ is true — it does, but what can we do?

Sepetys: I have seen these overlaps with every historical novel that I’ve written. It’s chilling because we want to progress, and we want to learn and grow and create hope for a more just future. But knowledge of history gives us perspective to the present. There are echoes, but there always are. It doesn’t matter what country or what history. I think that phrase ‘history repeats itself’ is true — it does, but what can we do?

Well, we can share the story. Knowledge of story helps facilitate human understanding. What if we can look through someone else’s eyes and consider their heart? That’s what too often doesn’t happen. There are these knee-jerk reactions, and we don’t take the time to walk around an entire topic and really understand it. We react instead of reflect. What if we reflect on several aspects of this story: How did a population of more than 20 million people get through it? Why do we know the story of the Berlin Wall, but we don’t know the story of the revolution in Romania? What determines how history is preserved and recalled? The book provides an opportunity for discussion and to ask questions. History sometimes divides us; but through reading books, maybe we can be united in story and study and remembrance. There’s a real power in that.

Chapter 16: Your book, and others you’ve written, reminds us that though this is something that keeps happening, we keep figuring out ways to move forward, and here’s how: by turning to each other. By being courageous, certainly, but also by seeing the inherent human value in each other.

Sepetys: And also knowing that sometimes it’s ok to say, I don’t know. That is a very honest and sometimes the wisest response.

Chapter 16: And to ask questions! Cristian often finds himself living inside questions, wondering if kids in other parts of the world live like he does, or if they could possibly understand how hard it is. In some ways, that’s the task of the book: to help young readers understand how hard this really was. What parts stand out to you as particularly effective in sharing that message?

Sepetys: One of the moments, which was painful for me to even write, was when Cristian sees the video that Dan’s friends have sent. Here are these boys in the West, in a kitchen that’s ablaze with light. They have more than one 30W lightbulb! The inside of the refrigerator has a light! And they open that refrigerator, and Cristian sees the food, and no one is rushing, no one is grabbing, no one is standing in line. And there is that bowl of bananas — something that was so unattainable to him, and they might even spoil; they might not even get eaten. When I spoke to Romanians during my interviews, they told me that seeing a magazine from the West, that window into democracy, it meant everything. There is a scholar who has argued that it was things like that — movies and music and magazines and books — that loaded the guns that killed Ceaușescu.

Chapter 16: What questions would you hope your readers would want to ask Cristian? Or his mother or sister?

Sepetys: I’ll think back to my own questions, the things I knew I wanted to ask. One thing is “What do outsiders not understand, and what do you feel we could never understand?” Because in asking someone that, we’re giving them a chance to build these bridges. When people feel misunderstood, that creates distance and isolation. It separates us. Currently, we’re separated, angry, and suspicious of each other. But what if we actually could build those bridges, just by asking: What did people not ask you? What can people never understand? Every time I asked that, everyone had a different answer.

Sepetys: I’ll think back to my own questions, the things I knew I wanted to ask. One thing is “What do outsiders not understand, and what do you feel we could never understand?” Because in asking someone that, we’re giving them a chance to build these bridges. When people feel misunderstood, that creates distance and isolation. It separates us. Currently, we’re separated, angry, and suspicious of each other. But what if we actually could build those bridges, just by asking: What did people not ask you? What can people never understand? Every time I asked that, everyone had a different answer.

Chapter 16: One thing a contemporary reader might not be able to understand is the radio. Both the physical object and the broadcasts from Radio Free Europe are terribly important to Cristian and his family. Do you think today’s readers can grasp something that will likely seem so foreign to them? Do they have anything close to that kind of shared cultural experience today?

Sepetys: I am so grateful that you brought this up. You know, my father fled from Lithuania when he was just a little boy, and they relied on radio broadcasts literally to save their lives. They listened to the radio and looked at the map, and that’s how they determined where they were going to run next, where they might be safe. To your question: I don’t know if people today could understand. Not due to any fault of their own, but simply because they haven’t lived through something like that. I don’t know if they can truly understand that voice of freedom and the influence it had.

Radio Free Europe deserves a book of its own, and I hope to write one. The danger that the broadcasters themselves went through was an element I wanted to include in the novel and just couldn’t. Many of those broadcasters were targeted. Even though they lived outside Romania, Ceaușescu sent his henchmen to hunt them down and poison or attack them. So again, what is the price of the truth? It’s hard to comprehend the importance of something like that and to understand the sacrifice that goes into just sharing the truth.

I think one of the best ways is to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. What if this old transistor radio that we have in the closet becomes our only source of information? We have no cell phone, no internet, no computer. This AM radio is all we have. What would that do? What would the effects be in a family? Is it unifying to the family? Or is it more like what Ceaușescu did — here’s two hours of TV, and that’s the story you’re all getting?

Chapter 16: Oh, so it could be a form of oppression or a means to freedom? What a complicated truth.

Sepetys: It is! It’s complex! But I think that anything that’s worth understanding is complex.

Sara Beth West is a writer and reviewer, usually found at sarabethwest.com. She lives in Chattanooga with her family, dogs, and a cat who always, always, always thinks it is time for dinner.