Something’s in the Water

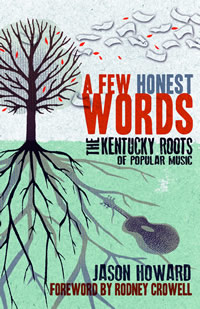

The rich and fertile ground of Kentucky roots music is the subject of Jason Howard

The ethereal melodies of Jim James, the heart-melting warmth of Naomi Judd, Dwight Yoakum’s hillbilly wail, and the rural rap of Nappy Roots represent a diverse sampling of artists whose sounds and styles have captivated audiences the world over. And though they are separated by generation and genre, they each draw inspiration from the same deep, plentiful well: the landscape, culture, and traditions of our neighbor to the north, Kentucky. In A Few Honest Words: The Kentucky Roots of Popular Music, Jason Howard profiles these and other artists from the Bluegrass State and explores the connections between art and sense of place.

Kentucky has been primarily known for its folk music: ballads and string bands in Eastern Kentucky, jug bands along the Ohio River, more thumbpickers than you can swing a cat at in the Western Kentucky coal fields, and, of course, bluegrass. But the modern sounds emerging from Kentucky are as varied as its landscape, encompassing not only country and folk but also indie-rock, jazz, gospel, blues, and rap. A Few Honest Words: The Kentucky Roots of Popular Music provides intimate profiles of a few Kentucky musicians who draw on their sense of place to inform their art. Among these venerable musicians is the iconic Naomi Judd, whose conversation with Howard over dinner in her library opens the book. She and Howard will appear together again at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books on October 12 at 3 p.m. in the Nashville Public Library Auditorium. All festival events are free and open to the public. Howard recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email prior to their event:

Chapter 16: It’s refreshing to read a perspective on Kentucky music that includes artists beyond the worlds of country, bluegrass, and folk. How did you decide which artists to include? Are you already tired of people telling you about the ones you left out?

Howard: It was hard work! I had such a long list of artists to choose from, and it was so challenging to narrow them down. Their music obviously had to resonate with me and reflect the influence of Kentucky, and after that diversity became the most important factor in a lot of ways. I wanted to make sure that all genres of roots music were represented, in order to move beyond this perception that Kentucky music is only bluegrass and banjos and fiddles. Of course bluegrass, country, and folk are very important, but so are jazz and gospel and blues and rock and rap. I threw in artists from all those genres, so there are not only country music legends like Naomi Judd and Dwight Yoakam and four-time IBMA [International Bluegrass Music Association] Female Vocalist of the Year Dale Ann Bradley, but also Joan Osborne—who has long straddled the lines of rock and soul—and rural rappers Nappy Roots.

Howard: It was hard work! I had such a long list of artists to choose from, and it was so challenging to narrow them down. Their music obviously had to resonate with me and reflect the influence of Kentucky, and after that diversity became the most important factor in a lot of ways. I wanted to make sure that all genres of roots music were represented, in order to move beyond this perception that Kentucky music is only bluegrass and banjos and fiddles. Of course bluegrass, country, and folk are very important, but so are jazz and gospel and blues and rock and rap. I threw in artists from all those genres, so there are not only country music legends like Naomi Judd and Dwight Yoakam and four-time IBMA [International Bluegrass Music Association] Female Vocalist of the Year Dale Ann Bradley, but also Joan Osborne—who has long straddled the lines of rock and soul—and rural rappers Nappy Roots.

Geography was important, too. Since Eastern Kentucky has received so much attention over the years for its contributions to roots music, I quickly decided to shine a spotlight on other regions of the state as well. Louisville and Lexington have really vibrant music scenes at the moment, and I made sure to include people like Jim James of My Morning Jacket and Ben Sollee and Cathy Rawlings of Agape Theatre Troupe.

I also wanted to help shatter this myth of Kentucky music being essentially “white music.” I point out in the introduction that Southern roots music is largely a blending of the British-Celtic and African-American traditions. The banjo, remember, was originally an African instrument, and Kentucky has a long history of great black artists and interracial collaborations, even in the time of segregation. This legacy is carried on in the work of musicians I’ve included like jazz pianist Kevin Harris and Nappy Roots.

And you’re exactly right—I’m already noticing that people at readings like to throw out names or wonder why so-and-so wasn’t included. I love that, actually—hearing their takes and suggestions and being a part of a dialogue that is essentially celebrating our artists. That’s the great thing about writing a book like this—there will always be a pool of talent to choose from if I ever decide to revisit it.

Chapter 16: You write that a strong sense of place is the true identifying mark of roots music, or “Americana,” as it’s come to be called. That umbrella genre has been steadily gaining in popularity for almost twenty years now. Do you think its popularity is attributable to a growing sense of placelessness?

Howard: I don’t think it’s a coincidence, as my generation changes jobs and moves back and forth across the country, that Americana music is booming. Today, so much of America is being lost through big-box stores and strip malls and subdivisions. Many towns across the country are virtually identical now. The great irony is that in the middle of this rootlessness and placelessness, we are also haunting the aisles of antique stores for vintage china and buying new tables and distressing them to look old. I think this is translating to music as well. At one point last year, there were five Americana albums on the Billboard Top 15 chart, which includes music from all genres. One-third of the albums on the chart at that moment were Americana records. That’s a pretty big deal.

Howard: I don’t think it’s a coincidence, as my generation changes jobs and moves back and forth across the country, that Americana music is booming. Today, so much of America is being lost through big-box stores and strip malls and subdivisions. Many towns across the country are virtually identical now. The great irony is that in the middle of this rootlessness and placelessness, we are also haunting the aisles of antique stores for vintage china and buying new tables and distressing them to look old. I think this is translating to music as well. At one point last year, there were five Americana albums on the Billboard Top 15 chart, which includes music from all genres. One-third of the albums on the chart at that moment were Americana records. That’s a pretty big deal.

Chapter 16: In the information age, critics and fans often lament that regional music is becoming, or in some cases has become, a thing of the past. After talking with artists drenched in sense of place, what’s your take on such statements?

Howard: I don’t buy the argument that we’re losing regional music. Quite the opposite—we’re living in a time in which regional music is being celebrated. Are lines of genres blurring? Sure. Are artists fusing different sounds and influences? Of course, and that’s really exciting. But regional music remains alive and well in both Kentucky and beyond. I think of bands like Old Crow Medicine Show, which is full-on regional music. Cities across the country have their own particular music scenes, some specializing in genres. Many artists are no longer striving to be signed by big labels. Instead, they’re making and releasing music on their own, on their own terms. It seems to be more of an egalitarian musical marketplace today, which in my opinion has allowed regional music to flourish.

Chapter 16: I’m glad you wrote about Chris Knight. He’s long been a favorite of mine, and you can never have enough songs about rivers and murder. Was he intimidating? I heard he once broke a man’s leg for being… mouthy.

Howard: Well, I didn’t get too mouthy with him, so I can’t tell you about the consequences of that. But I do write in the book that he looks like he could instigate an ass whipping if he took a notion. Chris and I had a great chat. He’s quiet at first, but once you get him talking about living in rural Kentucky he opens right up, and his story is so captivating. His new record, Little Victories, was just released, and I’m looking forward to hearing it.

Chapter 16: Central to A Few Honest Words is the idea that Kentucky is more “a spiritual state of mind” than a physical place of birth. I’ve lived and worked in Nashville for almost a decade now, but I was born and raised in rural Kentucky on the banks of the Cumberland River. Any spiritual advice for me?

Howard: I’d just say to remember the stories. That makes me think of country singer-songwriter Matraca Berg, whom I profile in the book. She was conceived in Eastern Kentucky, but was born and raised in Nashville. She heard stories of Kentucky from her mother and aunts, and spent weeks with her grandmother in Harlan County during the summertime. Her music is infused with their stories and spirit, and there’s no way that I would ever say that she’s not a Kentuckian, even though she’s never lived there. That’s testament to how the state gets under one’s skin.

Chapter 16: There is a strong literary quality in the work of each of the artists you write about, and they all have a knack for conjuring the idea of Kentucky, even if they haven’t lived there for years. If you were stranded on a desert island (or, say, Utah), how would you conjure Kentucky?

Howard: First I would remember the voices and people that I grew up around and the stories they told. I’d talk aloud and tell myself my Mamaw Howard’s story of living in a coal camp in Harlan County or of the time my mother chased my aunt with a pig’s heart during a hog butchering when they were growing up. But then I’d turn to the music. I’d probably be found belting “Guardian Angels” by The Judds, which opens with the lines A hundred-year-old photograph stares out from a frame/And if you look real close you’ll see our eyes are just the same. And then I might sing My Morning Jacket’s “Wonderful (The Way I Feel)” because it reminds me of a humid summer night in Louisville. That’s what would keep Kentucky alive for me.

Jason Howard will appear—with Naomi Judd—at Nashville’s Southern Festival of Books on October 12 at 3 p.m. in the Nashville Public Library Auditorium. All festival events are free and open to the public.