Sound Opinions

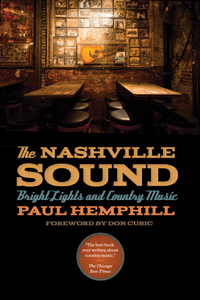

Back in print, The Nashville Sound is essential reading on country music’s upheaval and reinvention

Paul Hemphill’s The Nashville Sound captures the city and its most famous industry at a crucial time. New money is pouring in, real estate is going nuts, and transplants who don’t seem to get the local culture are arriving in droves, aiming to transform a once-sleepy town into something bolder, slicker, and more marketable. An industrial and cultural juggernaut, if you will.

The year is 1970, of course. Or is it? Round the numbers up, swap out a few details here and there, and this bit from page 37 could easily have appeared in the Nashville Post this year:

The year is 1970, of course. Or is it? Round the numbers up, swap out a few details here and there, and this bit from page 37 could easily have appeared in the Nashville Post this year:

When the city announced elaborate plans some five years ago for Music City Boulevard, land values on Music Row boomed overnight; one corner lot on Seventeenth sold for $39,000 in January of 1965 and the buyer turned down $160,000 for it the following January; a 50-foot lot could be had for $15,000 in ‘61 but was priced at $80,000 five years later. Every month, it seems, there is a story in Music City News or Billboard about another new building along The Row.

One big difference between then and now is that aggressively bland condos don’t feature in Hemphill’s account. But the boom-town disruptions of the time were, of course, also wrapped up in a musical identity crisis that will sound just as familiar: “A clear gap had developed between the traditionalists … and the impatient young ones who had piled into town,” Hemphill writes. “In a matter of only five years, Music Row had gotten away from the production of exclusively ‘country’ music and had headed off into all sorts of directions. It was still loosely called ‘country music,’ but a lot of it wasn’t.”

Forty-five years later, The Nashville Sound has been re-issued by the University of Georgia Press, and nearly every other page contains some echo of the debates currently swirling through the crane-pierced Music City skyline—debates over how much of the old must give way to bring in the new, how much money should be allowed to talk when transforming the city, and just what, if anything, “real” country music is or ought to be.

It’s not surprising that old debates resurface—or, depending on your point of view, continue unabated except for the names and fashions involved. (You could easily substitute “hip-hop” for “rock and roll” in any number of sentences in this book, or imagine that it’s “bro country” instead of “Countrypolitan” that’s under attack from traditionalists, and it will be apparent how little, at least on a surface level, has changed.) Nor is it surprising that cultural divisions that once seemed deep and unbridgeable will seem quaint with the benefit of time. But it’s also instructive to see how much of what was once considered beyond the pale by the likes of Wesley Rose (of Acuff-Rose publishing) and other Music City industry pioneers has since melted into the ranks of “classic” Nashville.

On one end, we have BMI’s Frances Preston telling Hemphill, in 1970, about Nashvillians’ ambivalence toward this new Music Row—“a little black cloud the city put over our head when they said they were going to put a boulevard through Sixteenth Avenue,” she says. On the other, we have Ben Folds’s open letter to Nashville from 2014, pleading for the preservation of RCA Studio A. “Music City was built on the foundation of ideas, and of music,” Folds writes. “What will the Nashville of tomorrow look like if we continue to tear out the heart of the Music Row that made us who we are as a city?” Given the right set of conditions, one generation’s money-grubbing interlopers can become another generation’s origin myth.

On one end, we have BMI’s Frances Preston telling Hemphill, in 1970, about Nashvillians’ ambivalence toward this new Music Row—“a little black cloud the city put over our head when they said they were going to put a boulevard through Sixteenth Avenue,” she says. On the other, we have Ben Folds’s open letter to Nashville from 2014, pleading for the preservation of RCA Studio A. “Music City was built on the foundation of ideas, and of music,” Folds writes. “What will the Nashville of tomorrow look like if we continue to tear out the heart of the Music Row that made us who we are as a city?” Given the right set of conditions, one generation’s money-grubbing interlopers can become another generation’s origin myth.

“The Nashville Sound was undergoing plastic surgery as the Sixties came to an end,” Hemphill writes, and The Nashville Sound is about as good a description of the surgeons and their operating rooms as you’re likely ever to read. And in addition to being a fascinating read, it’s also a solid reminder that Nashville has had a lot of work done, so to speak. If you’ve been to the Grand Ole Opry in the last ten years, it might amuse you to be reminded that it was once taboo to bring a drum kit onstage. But Nashville is famous for monetizing country music, not mothballing it. Writing in The New Yorker about the ascendant bro-country/R&B/something-or-other singer-songwriter Sam Hunt, Kelefa Sanneh notes that Hunt’s rise “is proof that Nashville is changing again, as it always does.”

But what makes The Nashville Sound tick so forcefully is not just that it traces the outlines of country-music-authenticity debates in a way that shows how they circle back on themselves. It’s the way Hemphill captures a very specific Nashville, at a very specific time, with a style that is both penetrating and lyrical. As good as Hemphill is with the history, the major players, the evolution of country music and culture, and all the rest, he’s at his best when simply observing people and listening to what they have to say.

Johnny Cash poking at his eggs; Bill Anderson in a robe, talking to a toll booth operator from his tour bus; Glen Campbell singing on set with his parents after his TV show finishes a taping; DeFord Bailey summoning a pack of hounds to howl through the reeds of a harmonica in his dusty shoe-shine shop—these scenes and more simply jump to life on the page. Helming a recording session with Kitty Wells, Owen Bradley asks her if she’s ready, “pushing a narrow-brim charcoal-colored tweed hat back on his head and shuffling toward the darkened control booth like a farmer going to check the henhouse.” Backstage before a show in Bakersfield, Merle Haggard takes a deep drink of bourbon and passes the bottle. “Then,” Hemphill writes, “he cradled his guitar in his forearms and sank back down in the chair, hunched over like an old linebacker taking a break while his team has the football.”

As vivid as these descriptions are, there are two areas where the 1970-ness of the writing can feel a bit dated: race and gender.

Hemphill is critical of white racism and doesn’t sidestep or gloss over it. If anything, he goes out of his way to cast rural whites as vicious segregationists and Nashville’s musical establishment as utterly squeamish about the prospect of a song depicting an interracial romance. (It’s fun to imagine time-traveling with a forty-five of “Accidental Racist.”) But in paraphrasing the thoughts of racist country folk, Hemphill deploys the N-word often enough that it’s jarring to 2015 ears.

And women, when they do appear, are almost always described in terms of their body or their association with a man. Nashville is a place where you see “leggy secretaries swishing down the sidewalks” of Music Row. Inside the offices, “eye-batting” secretaries “coo” at visitors. At one point in the book, he catches a rising star in concert: “girl singer Dolly Parton, a petite blonde of incredible vanilla-ice-cream beauty.” And when he introduces Dorothy Owens—Buck Owens’s sister and the head of his various enterprises, no small set of tasks—he sees fit to mention that she is “trim, efficient” and “unmarried.”

That said, from the first words of its preface—spent submerged in the smoky haze of Tootsie’s on a rowdy Friday night thick with booze and the kinds of aspirations that Music City can both foster and crush — The Nashville Sound is nothing short of captivating and essential to understanding the genre, whatever its boundaries may have been, or will be.

Steve Haruch lives in Nashville. His writing has appeared at NPR’s Code Switch, The New York Times, and the Nashville Scene, where is he is a contributing editor.