Southbound

Imani Perry explores the South’s centrality to the American story

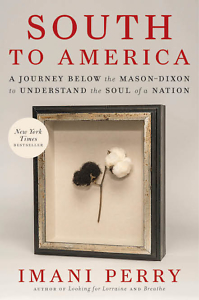

Imani Perry’s seventh book, South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation, begins with a dance. The introduction whirls from describing the steps of a French quadrille to recounting a brawl at a New Orleans ball celebrating the Louisiana Purchase. From there, it moves on to African dances on Congo Square, Dred Scott, John Smith, the Jim Crow era, and the Capitol attack of January 6, 2021.

By the end of the section, Perry makes it clear where this dizzying intellectual ramble is leading: The quadrille is a metaphor. “When it comes to the choreography, most folks are lost,” Perry writes. “They think they know the South’s moves. They believe the region is out of step, off rhythm, lagging behind, stumbling. It is a convenient misunderstanding.” By beginning her story with the imagery of dance, Perry is asking readers to refocus their eyes and see the whole moving picture: how aspiration and exploitation, commerce and cruelty, and race, poverty, and power have circled each other since 1492, or 1619, or 1776 (whatever national birthdate you choose) from sea to shining sea.

By the end of the section, Perry makes it clear where this dizzying intellectual ramble is leading: The quadrille is a metaphor. “When it comes to the choreography, most folks are lost,” Perry writes. “They think they know the South’s moves. They believe the region is out of step, off rhythm, lagging behind, stumbling. It is a convenient misunderstanding.” By beginning her story with the imagery of dance, Perry is asking readers to refocus their eyes and see the whole moving picture: how aspiration and exploitation, commerce and cruelty, and race, poverty, and power have circled each other since 1492, or 1619, or 1776 (whatever national birthdate you choose) from sea to shining sea.

Perry is, in other words, urging us to rethink the impulse to regard the South as a retrograde backwater, outside the flow of American history. “This country was made with the shame of slavery, poverty, and White supremacy blazoned across it as a badge of dishonor,” she writes. “To sustain a heroic self-concept, it has inevitably been deemed necessary to distance ‘America’ from the embarrassment over this truth. And so the South, the seat of race in the United States, was turned on, out, and into this country’s gully.”

To Perry, blaming the South for the nation’s sins represents a failure to understand the region’s centrality to America’s origin story and identity. With this book, she hopes to correct that misunderstanding. That said, South to America is difficult to categorize. Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, has packed many aspects of herself into this ambitious book. As a scholarly work, it ranges as widely as her own fascinations, from legal history and politics to hip-hop and the blues, poetry and literature, art, food, and the natural world. As a travelogue of the Southern states inspired by Albert Murray’s South to a Very Old Place, it’s personal and particular: “I passed over many famous places and lingered in unusual ones,” she explains.

The memoir aspect adds layers of complexity, thanks to the emotional power of memory and the contradictions we allow for when we belong to a place. Perry, an Alabaman in exile, confesses her biases: She’s inclined to defend her home region and even, in some ways, to romanticize it — or so she claims. I don’t see much romanticizing in these pages. Her commentary on the violence, greed, and racism that have undermined America’s stated founding principles since the nation’s birth is unsparing and deeply insightful. But her descriptions of nature — the fragrance of Mississippi’s Piney Woods, the lacework of Spanish moss — do betray a native’s love of Southern landscapes. And as the daughter of civil rights activists, Perry had an insider’s view of the movement and its veterans, whose stories populate her pages. If there’s anything romantic in Perry’s remembrances, it’s her reverence for the generations of defiant souls who resisted violence and disenfranchisement in ways both public and personal — through organizing, marching, writing, making art, and simply continuing to live, laugh, and find hope amid the constant heartbreak. Still, venerating them doesn’t strike me as a romantic impulse so much as a profoundly human one: “I love my people without apology,” Perry writes.

The memoir aspect adds layers of complexity, thanks to the emotional power of memory and the contradictions we allow for when we belong to a place. Perry, an Alabaman in exile, confesses her biases: She’s inclined to defend her home region and even, in some ways, to romanticize it — or so she claims. I don’t see much romanticizing in these pages. Her commentary on the violence, greed, and racism that have undermined America’s stated founding principles since the nation’s birth is unsparing and deeply insightful. But her descriptions of nature — the fragrance of Mississippi’s Piney Woods, the lacework of Spanish moss — do betray a native’s love of Southern landscapes. And as the daughter of civil rights activists, Perry had an insider’s view of the movement and its veterans, whose stories populate her pages. If there’s anything romantic in Perry’s remembrances, it’s her reverence for the generations of defiant souls who resisted violence and disenfranchisement in ways both public and personal — through organizing, marching, writing, making art, and simply continuing to live, laugh, and find hope amid the constant heartbreak. Still, venerating them doesn’t strike me as a romantic impulse so much as a profoundly human one: “I love my people without apology,” Perry writes.

Perry’s genealogical research and reflections on family are the story’s beating heart. The chapter on Nashville zooms in on her grandmother, Neida Garner Perry, who was sent from Alabama to Nashville to live with an aunt and attended the storied Pearl High. Her grandparents worked as a cook and a janitor at Vanderbilt but “remained outside of Vanderbilt’s gates”; whereas Pearl High, which Perry describes as “a superior segregated school built against the odds” that funneled Black scholars to Fisk and Tennessee State, was “a place of their own.”

In a chapter titled “Mary’s Land: Annapolis and the Caves,” Perry traces an ancestor mentioned in the 1870 and 1880 censuses in Maryland. Named Esther or Easter, born in Maryland in 1769 or Georgia in 1789, this incomplete knowledge fills Perry with both “reverence and sadness.” Like so many Black Americans, she mourns the missing pieces in Black family histories caused by official indifference to recording the details of their lives.

Perry’s elegiac final essay considers George Floyd’s death and the national eruption of grief and rage in its aftermath, then veers to Houston, Texas, where Floyd grew up. Her conclusion masterfully weaves together a story of the city, including a hurricane, an oil boom, immigration from parts even farther south, the Great Migration, and a Nigerian-American rapper — trust me, it all works — and ends with a reflection about how transforming deep truth-telling into art and action can banish poisonous mythos and broaden our sense of responsibility to each other. “After all, from the bottom, from the depths, from the fields, from the ashes,” she writes, “hope just keeps on rising and radiating off sweat-glowing skin in Southern heat.”

Kim Green is a Nashville writer and public radio producer, a licensed pilot and flight instructor, and the editor of PursuitMag, a magazine for private investigators.