Southern Graces

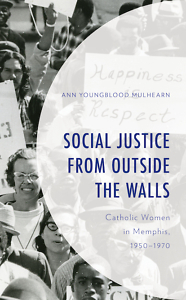

Ann Mulhearn explains how Catholic women shaped social justice in Memphis

“We can’t throw a nun out on the street!” exclaimed Henry Loeb, the mayor of Memphis. It was April 5, 1968, one day after the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and a group of progressive religious figures had marched from a church to City Hall, where they occupied the mayor’s office. One of the key protestors was Sister (Sr.) Adrian Marie Hofstetter. In Social Justice from Outside the Walls, Ann Youngblood Mulhearn recovers the history of six Catholic women who shaped the social justice landscape in Memphis, including Hofstetter, the nun who compelled Loeb’s frustration.

Mulhearn is a lecturer in the department of history at Middle Tennessee State University. She earned her Ph.D. in history from the University of Memphis, and she has also taught at the University of Tennessee at Martin and as a Fulbright Roving Scholar in Norway. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Mulhearn is a lecturer in the department of history at Middle Tennessee State University. She earned her Ph.D. in history from the University of Memphis, and she has also taught at the University of Tennessee at Martin and as a Fulbright Roving Scholar in Norway. She answered questions via email from Chapter 16.

Chapter 16: You tell the story of six Catholic women, three Black and three white. How did they come to social and political activism? Were there major differences across lines of race?

Ann Mulhearn: They all came to activism differently, but most through the church at some level, whether it was the Catholic Worker Movement or the Catholic Human Relations Council. Obviously for the Black women, race was also very much a motivating factor. Helen Riley talks about the sting of experiencing racism for the first time. That’s something the white women, however sincerely anti-racist they were, could never experience. And I think that is the major difference — the impact of racism on the Black women as individuals. Sr. Hofstetter told Bertha Gilmore to be Black, Catholic, and a woman in the Jim Crow South was a triple burden. The white women — even though they may have been discriminated against because of their gender, class, or faith — always had the protection of their skin. The Black women did not.

Chapter 16: In the book’s preface and acknowledgments, you discuss both your personal relationship to the Catholic Church and your relationships with the women you wrote about. How did your personal experience shape the scope and analysis of Social Justice from Outside the Walls?

Mulhearn: I grew in the same faith tradition and in the same geographic area as these women. Every time I spoke with one of them, I saw in them my Mimi, or my mother, or my favorite nun from elementary school. (That’s Sr. Imelda, btw.) My own life told me there were Catholic women across the South who shared these same commitments to social and racial justice, and it was tempting to expand my scope by including them. I decided, though, that these six women deserved to have their stories told separately, due to their deep, lasting personal connections to each other.

Outside of their tight network, they were also connected to events so much larger than themselves. Two worked with future saint Dorothy Day and one marched with Cesar Chavez. They had connections to the sanitation strike and Martin Luther King Jr. That consistent proximity to “history” was fascinating to trace. But this project definitely challenged my objectivity as a historian — I rewrote some sections several times to ensure I was not being too hagiographic of the women or the church.

Chapter 16: Historians of the Black freedom struggle in Memphis are more likely to know Jesse Turner, president of the NAACP, than Allegra Turner, his wife. Yet you profile Allegra, as well as other Black women such as Helen Caldwell Day Riley and Modeane Thompson. What can their lives teach us about Black women’s role in political activism?

Mulhearn: Black women did, and still do, a lot of the heavy lifting of community organizing. They weren’t looking to become famous; they did what they did because it was imperative to the survival of their communities. Historians have begun to look more closely at the role of Black women in society, and in the larger Civil Rights Movement, but I think more needs to be done. Black women were critical to the success of local and national movements. Literally — it would not have happened without them. Sometimes it will take teasing their stories out of the larger male-dominated narrative, as I have tried to do with Turner, who intentionally sublimated her own works to those of her husband.

Mulhearn: Black women did, and still do, a lot of the heavy lifting of community organizing. They weren’t looking to become famous; they did what they did because it was imperative to the survival of their communities. Historians have begun to look more closely at the role of Black women in society, and in the larger Civil Rights Movement, but I think more needs to be done. Black women were critical to the success of local and national movements. Literally — it would not have happened without them. Sometimes it will take teasing their stories out of the larger male-dominated narrative, as I have tried to do with Turner, who intentionally sublimated her own works to those of her husband.

Chapter 16: The reforms in the Catholic Church in the 1960s, often known as “Vatican II,” play a critical role in your narrative. How did Vatican II create new possibilities for Catholic women activists?

Mulhearn: In the church, women did the majority of the work on the ground while men were the public face. Nuns carried a disproportionate share of the labor in Catholic schools and hospitals, while lay women kept the local parishes running. They fundraised; they cleaned; they prayed; and of course, they had lots of children to keep the pews and schools filled.

With Vatican II, Pope John XII intended to “open the windows and let in the fresh air.” He, and later Pope Paul VI, believed that if the Catholic Church did not reform its position on the laity at large, and especially the role of women, it would not survive in the modern world. Part of letting in the fresh air involved opening the church up to the outside world — to become less insular, to encourage Catholics to engage with their larger secular communities. This was a radical shift for Catholics, especially for women.

Having the blessing of the church to engage in community work was critical to devout Catholic women. Vatican II not only made Catholic women more visible and valued within their faith, but also allowed them the spiritual room to fully engage in the secular social activism to which many of them felt called. By updating theology and dogma to reflect more modern secular perspectives on gender roles, Vatican II created space for women to be recognized in their own right, not simply as appendages to husbands and priests.

Chapter 16: The sanitation strike and assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 have received a great deal of attention from historians. How does a focus on Catholic women complement our understanding of this historical moment?

Mulhearn: The Catholic Church was relatively late to the Civil Rights Movement, particularly considering its inherent anti-racism. In “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King had chastened Bishop Joseph Durick for his cautious moderation. Yet Durick came out early and forcefully in support of the strike, giving that critical church blessing to the work these women were already doing. The high-profile Catholic support for the strike also shows there is more work to be done in examining the role Catholic theology plays in larger social movements.

The actions of these particular Catholic women speak to the idea that Memphis did not respond to the strike in a monolithic way. There had been ongoing efforts to address the economic and social distress of the Black community. These groups were able to mobilize in support of the strikers and their families quickly and effectively, which highlights the extraordinary community organizing skills of these women. The emergence of Sr. Adrian Hofstetter as the face of white support of the strike is particularly interesting. Here was a woman religious, in full habit, putting her life and livelihood in danger because it was the moral thing to do — the Catholic thing to do. She was Vatican II.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.