Still Alive

Death haunts the essays in Rachel Kushner’s The Hard Crowd

Back in her San Francisco bartending days, Rachel Kushner witnessed life in a way many of us never will. One night at the Warfield, a historic music venue, the Rolling Stones threw a party for their crew, and Kushner slung cocktails alongside Keith Richards. At a Tenderloin dive, one of her regulars was murdered, his head found in a dumpster.

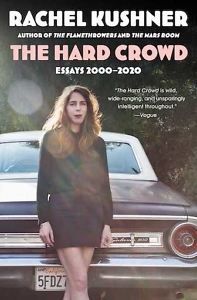

Those stories are shared in The Hard Crowd, an essay collection of personal narratives and critical writing spanning two decades. During these years, Kushner has become a literary icon. Her novels Telex from Cuba, The Flamethrowers, and The Mars Room were all finalists for prestigious awards. The Hard Crowd offers glimpses into experiences and settings that have informed her fictional world, but it triumphs not so much due to any calculated reveal of a seedy underworld as through Kushner’s crisp telling and refusal to sensationalize or sentimentalize.

Throughout, Kushner both cracks open the door to reveal her coming of age — she grew up in the Sunset District of San Francisco, a neighborhood close to Haight-Ashbury, in the 1980s — and directs our gaze outward, to places and people that have been the object of her roving curiosity and brisk analysis. The result is a tentative intimacy. We readers are the lonely hearts bellied up to the bar, and Kushner is both longtime listener and storyteller, willing to prolong the dream of connection, right up until she isn’t.

The collection opens with a gripping account of a motorcycle race on the Transpeninsular Highway in Baja California. Kushner was among the riders and suffers a crash that leaves her oddly liberated (as disasters often perversely do) — in this case, from a bad boyfriend. “So many bad things had happened — the crash, and then my bike getting stolen — but I felt strangely happy,” she writes. “I hadn’t been seriously hurt, and my attitude was intact. I was laughing things off.” In that line we hear something crucial to her voice: a burnished distance, an ability to laugh in the face of pain.

But she takes her subjects dead seriously. At the other end of the book, we reach a banger of a titular essay, an unflinching blues for a lost San Francisco, in which Kushner gazes back at the gritty places and people she knew as a free-range child and young adult, all of them vanished.

But she takes her subjects dead seriously. At the other end of the book, we reach a banger of a titular essay, an unflinching blues for a lost San Francisco, in which Kushner gazes back at the gritty places and people she knew as a free-range child and young adult, all of them vanished.

While The Hard Crowd is framed by the personal, more pieces than not focus elsewhere, on subjects as wide ranging as a Palestinian refugee camp, vintage cars, and prison reform. Kushner’s interest serves as connective tissue: “It is amazing what, from the past, you can drag into your net, only to find that has never left your net,” she writes in a pastiche essay, “The Sinking of the HMS Bounty.”

But what truly unites these pieces is the presence of death. So many figures killed or (nearly) forgotten. So many lives taken too early or through questionable circumstances. Settings where death lurks around every corner, books and films about disappeared characters. The late Denis Johnson. The late Clarice Lispector.

Even before reading Kushner’s take on Johnson’s posthumous story collection The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, I recalled his story “Out on Bail,” in particular its final line, as delivered by narrator Fuckhead: “I am still alive.” In these pages, no matter what or who she is writing about, you can hear the author considering this, again and again. You may be thinking it, too.

Kushner knows her past is, from a writerly perspective, rife with material. One could argue that most any life is, if given careful attention. But the characters in Kushner’s rearview are those unseen by many readers: outsized in their wounds and their proximity to the fire, their zeal for the precipices and depths of existence. “Sometimes I am boggled by the gallery of souls I’ve known,” she writes.” “The wild history, unsung … People who died or disappeared or whose connection to my own life makes no logical sense, but exists as strong as ever, in a past that seeps and stains instead of fades.”

Even in the earliest pages of the book, when I was thinking of those words of Johnson’s, I was also hearing the song “People Who Died” by The Jim Carroll Band in my head. I was not surprised to find the song mentioned by Kushner in the final essay. She, too, has always loved that song, which tracks. As does the end of that essay. It’s abrupt, chilly, haunting. “So. Get your own gig. Make your litany, as I have just made mine. Keep your tally. Mind your dead, and your living, and you can bore me.”

Of course we have been anything but bored. Of course we feel the pulse of life beating more fiercely in our veins. Of course this particular dismissal feels true to the collection’s ethos and to a layer of Kushner’s own life. Here she is, closing out our tab with brisk efficiency; it’s last call, she has other things on her mind, other places to be. We can, and we must, go now.

Susannah Felts is a writer based in Nashville. She is a columnist for BookPage, and her writing has appeared in The Best American Science and Nature Writing, Joyland, Oxford American, Guernica, Literary Hub, and elsewhere.