Stuck to the Bones

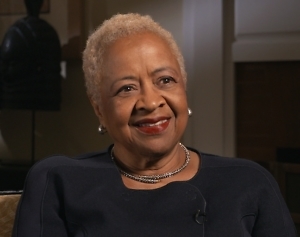

Margaret A. Burnham examines racist violence in the Jim Crow South

The Jim Crow era in the United States South involved more than segregation laws and disfranchised voters. As Margaret A. Burnham compellingly demonstrates in By Hands Now Known, Jim Crow was a system reinforced and defined by violence. Focusing on the period from 1920 to 1960, Burnham has written a fine-grained history of racial homicides and other violent crimes, while analyzing a wider set of legal shortcomings and injustices.

Burnham is the University Distinguished Professor of Law and Director of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern University. She began her career at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and in 1977, upon joining the Boston Municipal Court bench, she became the first African American woman to serve in the Massachusetts judiciary. In 2021, President Biden appointed her to the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board. She answered questions via email for Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: From a wider historical and geographical perspective, is there something unique about racial violence in the Jim Crow South? What function did it serve?

Margaret A. Burnham: Racial violence regulated citizenship in the Jim Crow South. Certainly, disfranchisement demarcated lines of inclusion and exclusion, but racial violence hardened, sharpened, and fortified those lines. Indeed, these were interconnected phenomena: disfranchisement enabled racial violence — Southern state and federal public officials were empowered by an electorate that did not include Black citizens — but racial violence also reinforced disfranchisement.

While W.E.B. DuBois pointed out that the “Black man is a person who must ride ‘Jim Crow’ in Georgia,” I argue in the book that the Black person was also someone for whom the courthouse doors were closed. Purposeful and relentless, casual and commonplace, violence could erupt at any moment and for the pettiest of reasons — failing to tip one’s hat, or say “sir,” or taking up too much space on the sidewalk, or angering a clerk in a shop. And the files, heretofore unexplored, reveal that a Black victim was helpless in the face of these attacks. If you argued with a white neighbor or “sassed” a bus driver, you could be killed for it, plain and simple.

Chapter 16: What was the research process for the book? How do you craft a history that analyzes both legal structures and regular people?

Chapter 16: What was the research process for the book? How do you craft a history that analyzes both legal structures and regular people?

Burnham: With a team of students over the course of a decade and a half, I collected 25,000 documents on Jim Crow-era killings targeting Black people. We built out the files to discern patterns across time and geography, and we met with families to share what we learned and incorporate their memories. Our main sources were federal records, primarily from the Department of Justice and the FBI, and the records of advocacy organizations such as the NAACP. While we were keenly focused on the legal history, we undertook this project for its “living history” since so many close relatives were still alive when we conducted our investigations.

Chapter 16: Why didn’t the federal government protect the civil rights of African American Southerners in this period? Was the problem legal, cultural, or ideological?

Burnham: Federal prosecutors had the legal authority to bring charges against the perpetrators of racial violence during this period, but they lacked the political will. The federal laws that criminalized violent interference with constitutional rights were adopted during Reconstruction but left to gather dust until the 1940s, and even then, applied only sparingly. It was not until 1939 that the Department of Justice opened a unit to address racial violence, and it took until 1946 for federal prosecutors to win, and successfully defend on appeal, a case of anti-Black violence under these Reconstruction statutes. More often, the Department of Justice deferred to local prosecutors who were loath to take these cases before unsympathetic jurors.

Chapter 16: The legal deck of cards, so to speak, was stacked against Black Southerners. Yet African Americans could still play their cards, right? What tactics and strategies could they pursue during this era in U.S. history?

Burnham: Resistance, in both its reformist and radical modes, came in many forms. Indeed, the killings were themselves often in response to the victim’s personal resolve to confront Jim Crow. In 1944, a soldier named Booker Spicely was killed by a bus driver in Durham, North Carolina, because he criticized Jim Crow seating. And in 1947, a recently returned veteran, Timothy Hood, was killed in Bessemer, Alabama, when he rejected the back of the bus. In 1943, Willie Lee Davis was killed, in uniform, by a police officer in Summit, Georgia, when he told the officer not to abuse him because, he proclaimed, “I’m not your man now, I’m Uncle Sam’s man.”

Both quotidian and subterranean, evidenced at funerals and in juke joints as often as in leaflets and editorials, resistance to Jim Crow saturated Black culture, traversing the entire social relationship with whites as individuals and with the white power structure. Resistance was the alterity that affirmed and created Black life.

Chapter 16: Is there one particular story in By Hands Now Known that most resonates with you?

Burnham: Edwin Williams’ death has stuck to my bones, probably because we have met so many of his family members, including his sons — who were children, and present, when he was killed. They are in their senior years now, and they had put this tragedy behind them when we sought to collaborate. In 1943, Edwin Williams lived with his family in Algiers, a neighborhood of New Orleans. As he walked home from church one weekday in April of that year, three white sailors attacked him and slashed him to death as his wife and young children watched. A jury acquitted the one man who was prosecuted, and the Coast Guard immediately sent him off to battle. That there was even a trial marked a measure of progress, but the acquittal, echoing, as it did, scores of others during this era, underscored how steep was the hill that Black victims had to climb to obtain justice. Especially moving to me is the fact that today, Williams’ son is the senior pastor of the church the family belonged to in 1943.

Chapter 16: In the book’s final section, you discuss the idea of reparations. What might reparations look like for victims of Jim Crow violence and injustice?

Burnham: This history is still close to us. With a little effort, we can identify those families affected by Jim Crow violence. We know what they were entitled to at the time of these events, and we know roughly what they were deprived of. We can calculate their losses, just as the losses of persons of Japanese ancestry were calculated to meet the terms of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. State and federal legislators should act now to redress these harms — which were facilitated if not caused by governmental policies and practices — while the victims’ succeeding generation is alive.

Aram Goudsouzian is the Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America.