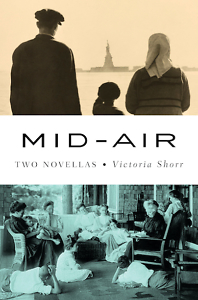

Sunset of the American Century

Victoria Shorr’s Mid-Air is an intimate portrait of 20th-century America

At first glance, the two novellas that comprise Victoria Shorr’s Mid-Air appear to depict families heading in opposite directions: a patrician New York family fading into obscurity and an immigrant clan rising from the working class to wealth and prominence. As Shorr demonstrates, though, families are complex systems that don’t fit neatly into conventional narratives of triumph or downfall.

The silk-stockinged Perkins family of the first novella, “Great Uncle Edward,” have certainly lost the apex status they attained in the decades between the world wars; and in the second novella, “Cleveland Auto Wrecking,” Sam White indeed rises from a penniless immigrant to achieve a position of comfort and influence for his family. But look more closely. Offshoots of the Perkins tree are constructing careers, connections, and prestige, while White’s oldest son finally rejects the trappings of wealth and instead surrounds himself with junk, a dirty echo of his family’s scrap yard beginnings.

The two stories do not share characters or settings, but they come together in a celebration of mid-century America. A haze of nostalgia hangs over Shorr’s picture of the 1950s, when single-income families could buy cars and houses, and the wealthy did not yet separate themselves in secure enclaves. “The truth was, life was good there then, and not just for the White brothers, but for most of the good solid citizens in those middle-sized towns in America in those days,” Shorr writes. “Post-WWII. Pre-Vietnam. When the kind of questions people were asking had answers, tried and true. Fair and square.”

That is not to say that Shorr’s mid-century America is a classless society — not by a long shot. Her characters are acutely conscious of the associations between appearance and social rank. In “Great Uncle Edward,” when the narrator sees her cousin Molly’s “lank and greasy hair” and “ill-fitting, wrinkled clothes,” she assumes that Molly is “a bum from the street.”

“Great Uncle Edward” is told from the point of view of the wife of the patriarch’s grand-nephew. This narrator (who remains nameless) recalls a dinner party in New York that she and her new husband threw 40 years earlier for an odd assortment of his family, all of them in their twilight years. The eponymous guest, after a long legal career that stopped short of crowning success, has outlived his beloved wife by several lonely decades. The other relatives have scrambled to create semi-satisfying existences after their family’s fortune was gutted by the Depression. “They were just one generation too far removed,” the narrator says.

“Great Uncle Edward” is told from the point of view of the wife of the patriarch’s grand-nephew. This narrator (who remains nameless) recalls a dinner party in New York that she and her new husband threw 40 years earlier for an odd assortment of his family, all of them in their twilight years. The eponymous guest, after a long legal career that stopped short of crowning success, has outlived his beloved wife by several lonely decades. The other relatives have scrambled to create semi-satisfying existences after their family’s fortune was gutted by the Depression. “They were just one generation too far removed,” the narrator says.

“Cleveland Auto Wrecking” tracks the upward fortunes of Sam White and his three sons, starting from Sam’s arrival at Ellis Island at 13, broke and illiterate. Though his hard-won success in Youngstown, Ohio, looms over the next generation, Shorr allows Sam’s story to recede as she rotates her focus among the sons and their wives. The episodes capture critical moments over a 90-year period, but they aren’t strictly chronological. For several scenes Shorr loops back to retell events from other perspectives, enriching our understanding of their Midwestern lives and of their transformation when the entire family follows Sam to the Southern California desert.

The central narrative question in “Cleveland Auto Wrecking” is whether Jeanette, a recent divorcée who was raised on the posh side of Youngstown, will stoop to marry one of Sam White’s sons, “a permanent slumming expedition.” Jeanette, who goes by the nickname Ned, is attracted to Roy, the oldest son, but he will never resemble the country club men she is familiar with, “no matter how many Brooks Brothers shirts Ned put on him.”

Despite the overlap in ‘50s sentimentality, Shorr’s novellas are strikingly different in milieu and outlook. The Whites are relentless businessmen with a knack for turning “rubble” into cash. They have no use for books and little patience for leisure activities. “Great Uncle Edward,” by contrast, is saturated with literature. Edith Wharton was a guest at the Perkins home; Edward’s brother, Max, was the famous Scribner’s editor who ushered Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Wolfe into fame. The narrator sprinkles the tale with references to Proust, James, Gibbon, and Austen. Though the family no longer boasts money or prominence, an air of Bohemian grandeur clings to its survivors.

While essentially plotless, both novellas compel readers with sympathetic portraits of colorful characters. In quick brushstrokes, Shorr reveals their inner lives, replete with nuances and contradictions.

The signal achievement of Mid-Air is its illumination of a period of American history that is fading from living memory. The narrator of “Great Uncle Edward” listens closely to the old man’s stories because, though they are “family tales,” they “shed light well beyond the circle they depicted.” The White family saga, too, resounds with cultural significance as Sam White’s sons attempt to grab their own “golden American twentieth century life.”

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.