Sweet Songs Never Last Too Long

A fan remembers 40 years of following John Prine

The first time I saw John Prine in concert, it was hard to know what to make of him. As a college student at the University of Kentucky in the late 1970s, a music fan since childhood, I was already a veteran of many concerts, spanning rock to folk to R&B to jazz to church music. But who had ever seen anything like this guy?

In the student center auditorium on UK’s campus, I sat cross-legged on the floor with the rest of the crowd (for a $6 student ticket, they didn’t budget for chairs), watching and listening to this odd fellow performing solo with a raspy, nasal vocal, a lone guitar, and irresistible energy. He boomeranged around the stage like a kid on a pogo stick. Can this guy even sing? I remember wondering, before realizing fairly quickly that with John Prine, that question was beside the point.

The draw for me that night was his seminal song “Paradise,” released about five years earlier on his self-titled debut album but gaining increasing recognition in tandem with a pressing issue of the times: opposition to the strip mining used to harvest the region’s rich coal veins, with catastrophic results for the terrain left behind. “Paradise” became a theme song for the regional environmental movement, which was very active on campus in those days, and nearly everyone in that room could sing along with the chorus:

And Daddy, won’t you take me back to Muhlenberg County

Down by the Green River where Paradise lay

Well, I’m sorry my son, but you’re too late in asking

Mister Peabody’s coal train has hauled it away

The lyrics to “Paradise” totaled all I knew about John Prine when I scraped together the price of the ticket and showed up that first time, beginning a relationship that lasted until he left us last April, an early victim of the coronavirus pandemic.

John’s family left Kentucky in search of work before he was born, but “Paradise” remains an indelible symbol of his ties to the state that was home to his parents and the center of so many of his childhood memories. I heard him say more than once that he never meant it as a political statement, yet as the decades passed the song achieved anthem status, a testimony to the broader power of John’s deceptively simple storytelling and his iconic stature with the generations that succeeded him. The last time I saw him perform at Nashville’s historic Ryman Auditorium, in the fall of 2018, “Paradise” provided the groundswell conclusion that has become a closing hallmark of so many Ryman events. All the artists who had joined John on stage earlier in the evening, and maybe even a few who just showed up for the end, gathered around a handful of mics for “Paradise,” taking turns stepping up for solos of the individual verses. Of course, the audience joined in as the anthem swelled in near-operatic fashion to the evening’s close.

But back to that boomeranging around the stage thing for a second, all those years ago: Was he drunk, or high, or some combination of the two? It sure seemed like it at the time, but nearly half a century later, I wonder. In countless venues across those decades, I watched John onstage, his energy growing as the evening progressed. More and more as the years went on, he bestowed such love on the crowd, and the crowd gave it back, a cycle that built and built until he might end the evening by literally dancing off the stage, the picture of a natural high if ever there was one.

As we followed him on his 50-year journey as the acoustic everyman, the poetic chronicler of the commonplace and the tragic, the jocular storyteller at the dinner table we all joined — in our hearts, of course — I wondered if that high, those dance steps, sprang as much from love as any stimulant. If substances contributed, they couldn’t take the place of the feeling that poured directly from the heart.

John’s humor was the B side to the dark heartbreak in his work, never much daylight between the two. But I wonder if history will view his humor with the same respect afforded to his more serious work. I hope so. Funny stories were everywhere: He told them on stage, in interviews, captured them in songs like “Dear Abby” — many pointed squarely at himself. That ability to laugh at himself was my favorite among the many things I admired about him.

Dear Abby, Dear Abby

My feet are too long

My hair’s falling out and my rights are all wrong

My friends they all tell me that I’ve no friends at all

Won’t you write me a letter, won’t you give me a call

Signed Bewildered

John’s generosity and gracious determination to share his spotlight were a joy to watch. He often toured with young, up-and-coming artists, singing with those lucky individuals on stage, recommending their work, supporting their progress both personally and professionally. That spirit extended to those who contributed behind the scenes. Producer Matt Ross-Spang, who worked on the Nashville studio team producing John’s last album, The Tree of Forgiveness, described the recording sessions to the Commercial Appeal as “a surreal couple of weeks”:

Ross-Spang recalled that Prine showed up at RCA Studio A every day in a different vintage Cadillac. “Eventually, he gave one to Ross-Spang — a dark red 1993 ragtop El Dorado.”

“So, the man gave me a car, but that was really the smallest gift he gave me,” Ross-Spang said, citing the other “gifts” of “his friendship, his love.”

Over the years we watched and waited hopefully as John overcame a remarkable series of physical challenges, including heart problems and two varieties of cancer. Surgeries permanently changed the angle of his neck and fueled more self-deprecating humor in the form of his wisecracks about the changes in his voice. On a recent road trip as I progressed through a long Prine playlist, I was struck anew by the differences between his voice in the early days and the more recent, post-surgery work.

Perhaps because — as my own birthdays whir past — I increasingly admire artists who continue creating until the end of life, my heart voted overwhelmingly for the voice altered by time and illness. It had raw nuances hinting of survival, melancholy, grief, longing, and the heartbreaking speed of the passage of time. John, too, admitted he preferred the sound of his voice after he recovered from cancer. Here’s what he told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross in 2018: “I think it improved my voice, if anything. I always had a hard time listening to my singing before my surgery.”

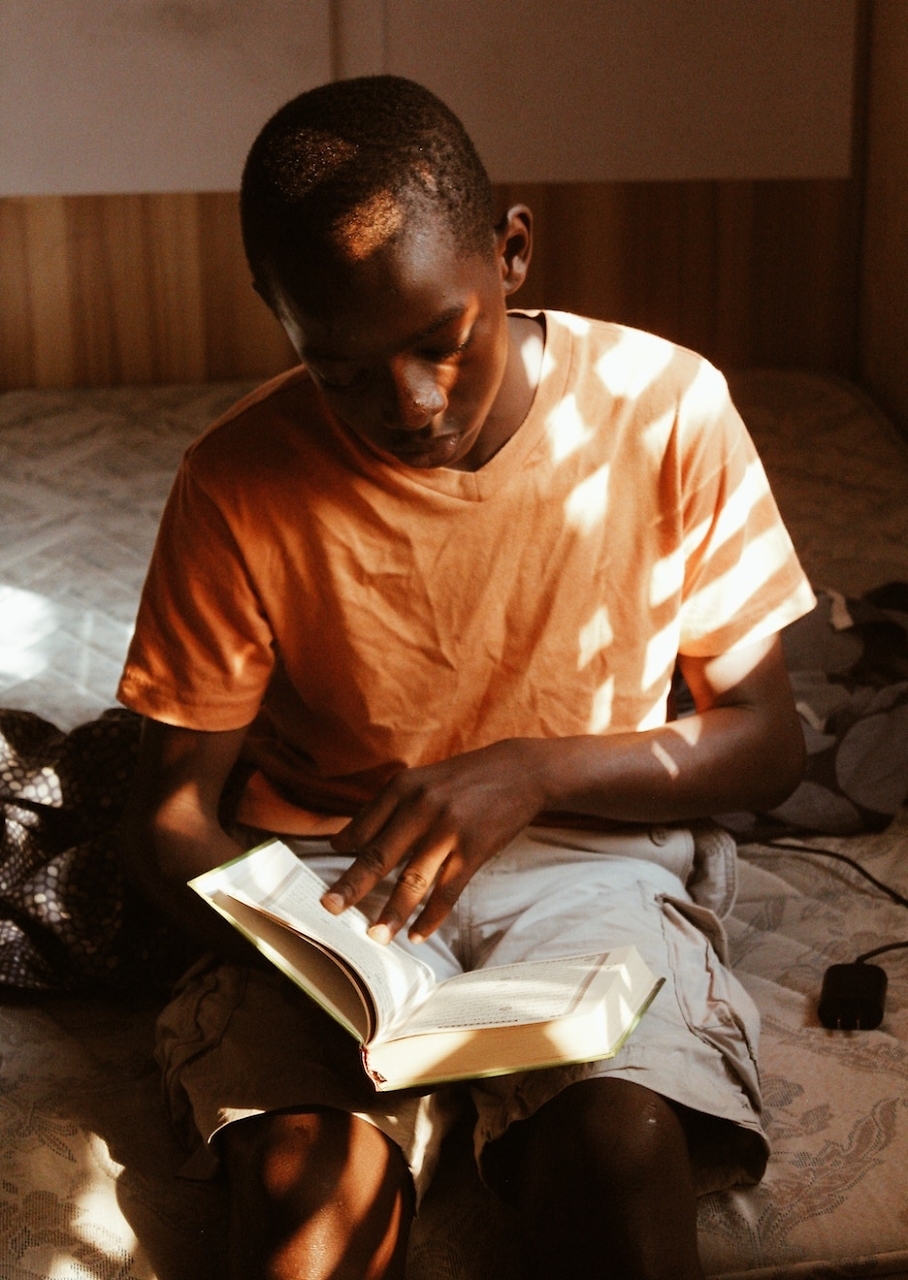

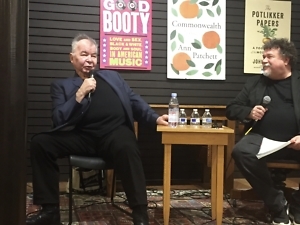

In 2017, John published Beyond Words, a volume of handwritten lyric notes, photographs, and chords to his songs. I nabbed a ticket to a promotional event at Parnassus Books in Nashville, where John agreed to be interviewed on stage and play a few songs, with the proceeds benefitting a local charity. Knowing it would be packed, I turned up early and was happy to perch with a decent view, standing, among the bookshelves on the side wall. I had bought my ticket too late to get an assigned seat facing the small stage area.

In all my years of fandom and concert-going, I never scored a front-row seat, but that night my luck suddenly changed. When some ticket-buyers failed to show on time, the diligent Parnassus staff began filling the open seats with folks like me from the wings. My heart leaped and continued racing when the manager waved me into a single open chair in the very center of the front row. When our hero stepped to the mic with his guitar a few minutes later, he was barely 4 feet away. Never a groupie type or celebrity-worshipper for celebrity’s sake, I was astonished at my reaction. I had to work to slow my breathing and keep my face composed.

All that effort worked just fine until he started into “Sam Stone,” the dark tale of the traumatized Vietnam vet who dies of a drug overdose. In this small, intimate setting, he played and sang it slowly, almost as if he was recalling the story new again, picking out the simple chords on the old guitar in the total silence of the big room.

There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm where all the money goes

Jesus Christ died for nothin’ I suppose

Little pitchers have big ears

Don’t stop to count the years

Sweet songs never last too long on broken radios

I refused to move or grab a Kleenex when my tears came, so they streamed down unabated, a tribute to him, to the years gone by, to the song and the countless victims who suffered the pain portrayed in it. As he moved comfortably and gently on his feet at the microphone, turning to different parts of the audience, I looked up again, and our eyes suddenly locked. I managed, just barely, to choke back a sob when I saw his eyes fill with tears, as well.

I remember exactly where I was when I learned that John had died. Watching for news and praying for days while he breathed through a ventilator in a hospital bed at Vanderbilt Medical Center, part of me thought the indomitable character would surely survive this one, too. In those blinding early days, we were only beginning to understand the horrible impact of this new virus. A dear friend and fellow fan texted a few lines from “When I Get to Heaven,” and I knew he was gone.

When I get to heaven

I’m gonna shake God’s hand

Thank Him for more blessings than one man can stand

Then I’m gonna get a guitar

And start a rock-n-roll band

Check into a swell hotel

Ain’t the afterlife grand?

Even after 40-plus years as a fan, the depth of my grief over John’s passing has surprised me. Only recently have I been able to put his songs back into listening rotation. It’s difficult, somehow, to separate it from the broad-based grief over our shared global tragedy; it is nearly impossible to disentangle all the emotions that have raged over this past year. I am among those who believe that John did his very best work at the end of his life, so there has been some small comfort in watching the honors continue to roll in, accolades recognizing brilliant particular work along with a lifetime of achievement.

Of course, I have my extensive collection of his recordings, posters from his concerts, a signed volume of his book — all enduring testimony to the singular nature of John’s body of work and the joy he created. Still, the loss of his presence remains wide and deep and hurtful. As the world inches back toward open life, there will be no John in Nashville showing up to help out at benefits, no John greeting friends at the local meat-and-three (where, the stories go, vegetables rarely made it into his “three”), no John celebrating New Year’s with his friends on stage and with us, no John telling jokes and encouraging young artists and giving away cars.

It feels like losing a beloved uncle whose door was always open, whose porch chairs were populated by the quirky and the downtrodden and the brilliant, in equal numbers, who knew everyone in every chair for their oddities and frailties and fears and loved each of them equally without judgment. Anyone who has a soul like that in their life is richly blessed, indeed. Perhaps John’s greatest legacy is making all of us feel like accepted, beloved friends — even those of us who never actually met him.

* “Paradise” and “Sam Stone” from John Prine (1971); “Dear Abby” from Sweet Revenge (1973); “When I Get to Heaven” from The Tree of Forgiveness (2018). More info at johnprine.com and Prine Shrine.

Copyright © 2021 by Eve Hutcherson. All rights reserved. Eve Hutcherson started writing as a journalist covering Thoroughbred horse racing for an international trade publication. She has since published on topics ranging from vintage car shows to healthcare, and her current work focuses on the unexpected and often humorous side of grandparenting and mid-life. She lives in Nashville.