Tender and Tragic

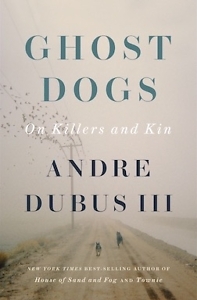

Andre Dubus III’s essays are probing and deeply personal in the collection Ghost Dogs

You might take up Andre Dubus III’s Ghost Dogs: On Killers and Kin with a box of tissues and a bottle of bourbon close by.

The tissues are for the times you may tear up a little, amid moments of heartbreak and the author’s painful honesty. The bourbon will pair well with the grittier passages, the gunplay and such, the men-being-men moments of which there are many.

That’s quite a range for a single book, even a collection of essays written over some 25 years and originally published in places as varied as Vice and Knitting Yarns: Writers on Knitting. But this is Dubus. He’s a complex fellow, contains multitudes. He’s a sensitive soul, clearly devoted to his wife and children and drawn to the power of words on a page, “the honest labor of writing itself.” He’s also deeply scarred by the poverty of his youth and feelings of inferiority it caused; when it comes to wrestling demons, he’s usually willing to pick a fight.

All of which makes for a compelling collection. It helps, of course, that Dubus, author of such acclaimed works as the novel House of Sand and Fog and the memoir Townie, is a deft writer of deep conviction. His aim, always, is the deeper truth. His style — readable but writerly — helps, too.

The opening essay, “Fences and Fields,” reads like a short story, sings like one, could be one — if not for the unabashedly hopeful note on which it ends.

In a late scene, Dubus is sitting by a river with his brother and their father. They’re celebrating, with beer and cigar, the birth of his daughter. He’s filled with gratitude, even as he knows he should be worried about his lack of steady work, about how he’ll support this burgeoning family. In that moment he somehow knows it will all work out: “Because how can there be green fields inside us and no food on our tables?”

The second essay, “The Golden Zone,” concerns his youthful turn as a bounty hunter’s assistant. It’s set in Mexico, on the trail of “a man who got paid to kill people.” It’s as terrifying as the first essay was sweet.

The second essay, “The Golden Zone,” concerns his youthful turn as a bounty hunter’s assistant. It’s set in Mexico, on the trail of “a man who got paid to kill people.” It’s as terrifying as the first essay was sweet.

As “The Land of No” opens, Dubus is living in New York City with his 23-year-old girlfriend, who is “blond and beautiful, with the erect posture of the ballet dancer she’d once been.” Oh, and she has a $2 million trust fund. But a dream life in a Manhattan apartment is no match for the haunted houses of Dubus’s hardscrabble youth — a recurring theme of the book:

We moved often, one year three times, always for a cheaper rent. We kids spent too much time watching television, roaming the streets, getting high on stoops waiting for the school bus. Children got pregnant at fourteen, boys went off to reform school and later prison, my best friend to an early grave, his own knife stuck into his liver by the girlfriend he’d tormented far too long.

Pointed and poignant — the stuff of which stories are made.

But Dubus isn’t pandering. He’s not slumming. He lived this life — poverty, violence, bullying, feelings of inadequacy, the implications of eventually fighting back — and writes about it with a bared soul. “I did not feel sorry for myself; I felt the superior pain of the inferior, the pride of the sufferer, the shame of the poor,” he writes.

The centerpiece of the collection, “If I Owned a Gun,” is about Dubus’ long relationship (starting from age 6) with firearms, about their troubling allure, about how “guns, especially loaded ones, call us to use them.” He writes about the time he nearly shot his brother, the time his father nearly shot him — frightening accidents that could have been fatal.

He tells also of the time when, unable to otherwise expel a bird that’s entered his tiny New York apartment, he shot the thing with his rifle. A rifle. Inside an apartment. In a city where people live on top of each other.

On the floor the dead bird looked smaller than it had earlier. On the second highest shelf of my bookcase, bits of the bird’s feathers were stuck to spots of bright blood on my hardcover Faulkner, Tolstoy, and Chekhov.

Dubus doesn’t play this scene for laughs, mind you. Dubus doesn’t play.

Everyone should read “If I Owned a Gun,” for the conversations it might spark. But in a country with more guns than people, how could an essay accomplish what school shootings don’t? But at least we have Dubus — open to change, able to evolve, and, in the end, to wrestle the gun from his demons and kick it to the corner.

From his love-hate relationship to guns (and dogs; see the heartrending title essay) to that time he learned to knit so he could make his aunt a scarf for Christmas, we get Dubus in all his complications. We get a serious writer in search of hard truths. We get this fine collection of essays, far-flung and unflinching, tender and tragic.

David Wesley Williams is the author of the novels Everybody Knows (JackLeg Press, 2023) and Long Gone Daddies (John F. Blair, 2013). His short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Kenyon Review Online, and in Akashic Books’ Memphis Noir. He lives in Memphis.