Terror in Oxford

In Riot, Edwin E. Meek’s photographs document the 1962 mob violence at Ole Miss

On September 30, 1962, after a lengthy legal battle that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, James Meredith was about to enroll as the first African-American student at the University of Mississippi. Segregationist opposition was intense, and when a large contingent of U.S. Marshals arrived on campus to protect Meredith, all hell broke loose. A long night of violence, ultimately quelled by several thousand federal troops, left two people dead and scores injured.

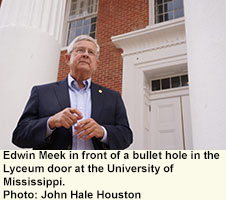

Riot: Witness to Anger and Change, a stunning collection of photographs by Edwin E. Meek, documents the rioting and the events surrounding it, as well as Meredith’s first days as a student. Personal recollections from Meek, journalist Curtis Wilkie, and former Mississippi governor William Winter provide context for the photos, giving a powerful sense of the fraught mood of the time and the very real terror that briefly ruled Oxford.

Riot: Witness to Anger and Change, a stunning collection of photographs by Edwin E. Meek, documents the rioting and the events surrounding it, as well as Meredith’s first days as a student. Personal recollections from Meek, journalist Curtis Wilkie, and former Mississippi governor William Winter provide context for the photos, giving a powerful sense of the fraught mood of the time and the very real terror that briefly ruled Oxford.

Meek, who would go on to become a journalism professor and Vice Chancellor for Public Relations at Ole Miss, was a graduate student in 1962, working for the university’s public-information office. When the violence began, his insider status gave him a great advantage over the dozens of reporters who had come from all over the world to cover Meredith’s arrival on campus. These outside journalists were immediately targeted by the white mob and had to lay low. (One of the riot’s two fatalities was a French reporter, Paul Guihard, who was apparently shot in the back at close range. No one has ever been charged with the crime.) Meek was recognized as one of the university’s own, so he and pal Larry Speakes—Ronald Reagan’s future press secretary—could move around more freely.

Photos of the early hours of the unrest confirm Meek’s recollection of a gathering with the air of a pep rally. In one shot, a boy dressed up as Johnny Reb, perched on the shoulder of another boy, waves a Confederate flag and smiles for the camera. In another, a gaggle of grinning students surround a trumpeter playing “Dixie.” Many of the students had in fact been at a football game in Jackson the previous day, during which Governor Ross Barnett—the undisputed villain of this story—riled the crowd at half-time with dog-whistle demagoguery about loving Mississippi’s “customs” and “heritage.” Pictures from the game show majorettes and cheerleaders wearing the same slightly crazed smiles as those young men in Oxford who are about to start hurling bricks and setting things on fire.

Images from later in the riot are grim indeed: a line of marshals in gas masks, torched cars flaming in the darkness, soldiers arrayed across a street in downtown Oxford. Much of the violence was committed by non-students, including armed reactionaries who had traveled to Ole Miss with mayhem in mind. Parts of the campus rang with gunfire, and Meek’s photos capture a thoroughly warlike scene that is hard to reconcile with the sleepy, provincial locale seen elsewhere in the collection.

Many of Meek’s photos of James Meredith show a man looking remarkably calm and confident under what must have been extraordinary pressure. The book juxtaposes a shot of handsome, smartly-dressed Meredith smiling as he talks to reporters with one of a vulture-like Barnett grinning and waving at a small crowd. Despite their similar poses, hero and villain could not be less alike. Later photos of Meredith in the classroom, sitting alone as white students walk out, reveal more of the pain and anger he must have felt. One particularly poignant shot captures him in profile, eyes cast down at his desk, a pencil held tight with both hands. He looks like a man quietly braced against an experience that is very difficult to endure.

Many of Meek’s photos of James Meredith show a man looking remarkably calm and confident under what must have been extraordinary pressure. The book juxtaposes a shot of handsome, smartly-dressed Meredith smiling as he talks to reporters with one of a vulture-like Barnett grinning and waving at a small crowd. Despite their similar poses, hero and villain could not be less alike. Later photos of Meredith in the classroom, sitting alone as white students walk out, reveal more of the pain and anger he must have felt. One particularly poignant shot captures him in profile, eyes cast down at his desk, a pencil held tight with both hands. He looks like a man quietly braced against an experience that is very difficult to endure.

In lieu of descriptive captions for the individual photos, relevant quotations are scattered through the collection. Meek includes comments, taken from a variety of sources, from all the principal players in the incident, as well as from people like civil-rights leader Medgar Evers. Excerpts from the recorded phone calls of Barnett and President Kennedy accompany pictures of state troopers and U.S. Marshals milling about before the riot. A telling exchange between Meredith and a reporter (“I’ve been living a lonely life a long time”) shares the page with images of Meredith alone in the classroom.

Although history lovers might long for the missing documentary details, this impressionistic approach makes for far more powerful storytelling. The reminiscences of Meek and Wilkie, in any case, provide a fairly detailed account of events. Wilkie was also an Ole Miss student at the time and, like Meek, witnessed the riot firsthand. The book includes a map he sketched on spiral-notebook paper the morning after the riot that shows how the fighting occurred across campus and where the bodies of Paul Guihard and Ray Gunter, an Oxford man who was killed by a stray bullet, were found. It’s a useful and sad artifact.

But the facts Meek and Wilkie remember are perhaps less valuable than the perspective they provide on what it was like to be a white Mississippian in 1962. Wilkie describes Barnett’s half-time speech as “blood curdling to me because I objected to so much of what was going on.” Meek, also speaking of Barnett’s segregationist rhetoric, says, “I hate to admit it, but it seems to me that, prior to the riot, I didn’t have a full understanding that it was just wrong.” That two intelligent young people of good will could respond so differently to Barnett is a sharp reminder of how thoroughly culture can override gut opposition to injustice. Good and evil that seem perfectly clear in retrospect aren’t necessarily so obvious when they’re being played out right in front of you. Sometimes it takes a terrible event—and a person of extraordinary courage like Meredith—to make the truth visible.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.