The Arc of Memphis History

In a new essay collection, Aram Goudsouzian and Charles W. McKinney Jr. consider race relations in the Bluff City

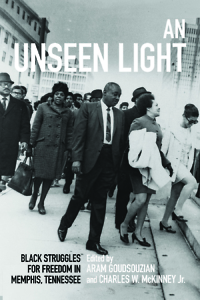

In An Unseen Light: Black Struggles for Freedom in Memphis, Tennessee editors Aram Goudsouzian and Charles W. McKinney Jr. have collected a series of essays that chronicle the arc of African-American history in the Bluff City as it slowly—many would say too slowly—bent toward justice.

The book challenges the common narrative that racial harmony in Memphis is what led to its relative calm before and during the civil-rights era. “Violence perpetrated against black Memphians begat political organization and incremental increases in political power,” McKinney writes. “Black people from all walks of life shaped the pursuit of greater freedom by laying claim to their humanity and mounting an array of seen and unseen actions.” This counter-narrative continues throughout An Unseen Light, from the lynching of Ell Parsons in 1917, through the rise and fall of E.H. “Boss” Crump, through the birth of the blues and the famous Sun and Stax labels, to the assassination of Martin Luther King and the violent protests that followed, and into the new century.

In his essay on the 1917 Parsons lynching, Darius Young writes that Memphis “provided a seeming refuge for rural African Americans escaping from the hostile racial atmosphere of the Mississippi Delta. Memphis was the only city in the region that had a substantial black professional class, and thanks to the activism of its African American leaders, black Memphians still had a political voice.”

But from the end of the Civil War until now, as Aram Goudsouzian points out, Memphis has offered its black residents only an approximation of equality. “On the one hand, black Memphians shared the racial burdens and discontent that plagued their neighbors in Mississippi. On the other hand, the city had established patterns of accommodation that both fostered and fettered black protests for freedom.”

Beale Street, once a wealthy white enclave, became Main Street for black Americans, bustling with shops, black-owned banks, saloons, and cafes. By 1937, nearly 100,000 African Americans lived in Memphis, representing forty percent of the population. These black citizens had the franchise, and as Crump rose to power in the 1920s he paid the poll tax for black voters in exchange for their vote. At the same time, he offered an iron-fisted response to any agitation for true power sharing, a response enforced by police brutality and racist vigilantism.

After Crump’s death in 1954, the black community launched an effective push for electoral and social equality. The key driver for change was the Shelby County Democratic Club, which in 1964 had 101 individual neighborhood clubs and 7,000 members. Eighty-seven community leaders sat on its board, thirty-six of them women. A total of 95,000 black residents, of a potential 119,000 eligible citizens, were registered to vote.

Kennedy’s election to the White House was another factor in the rising power of black Memphians. “The fact that they had a better relationship with the Kennedy administration than did white officials in Memphis shows their political skill and acumen,” Elizabeth Gritter writes. “In a few short years, they went from running for public office to winning public office while holding the balance of power in elections.”

Kennedy’s election to the White House was another factor in the rising power of black Memphians. “The fact that they had a better relationship with the Kennedy administration than did white officials in Memphis shows their political skill and acumen,” Elizabeth Gritter writes. “In a few short years, they went from running for public office to winning public office while holding the balance of power in elections.”

But political and social gains were hard-won and often ephemeral, as several essays in An Unseen Light point out. Memphis music legend Rufus Thomas worked nearly his whole life in a factory to pay his bills. He was short-changed in both pay and production credits at Sun and at Stax, writes Charles L. Hughes in an essay titled “You Pay One Hell of a Price to Be Black,” an observation attributed to Thomas.

The tension between the expectation of justice and the reality of limited opportunity continues in the new century, McKinney notes. Memphis was recently named the poorest metropolitan statistical area in the United States, and citizens have picketed for jobs and a $15 an hour minimum wage. Yet, McKinney writes, “In the face of enduring inequality, black folks and their allies are deeply invested in what [Martin Luther] King once called ‘the long and bitter, but beautiful struggle for a new world.'”

Lyda Phillips is a veteran journalist who grew up in Memphis and has earned degrees from Northwestern, Columbia, and Vanderbilt universities. The author of two young-adult novels, she worked for United Press International before returning to Nashville.