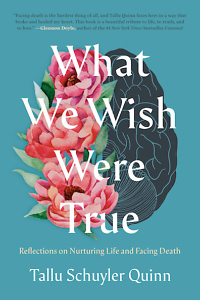

In What We Wish Were True, Tallu Schuyler Quinn prepares herself and her readers for the final surrender to death.

In the summer of 2020, while the world confronted a pandemic and a reckoning with national and global injustice, Quinn learned she had glioblastoma, an incurable, malignant brain tumor with a life expectancy of two years. At age 41, Quinn had already lived what she calls a “charmed and wonderful” life. She had felt loved and supported by family until she created a family of her own with her husband, Robbie, and their two young children, Lulah and Thomas.

Through a master’s degree in theology, work as a cook in a national anti-poverty movement, time living in Nicaragua, and over a decade as executive director of The Nashville Food Project, Quinn wrestled with ultimate concerns: her faith in God, racial and economic injustice, global degradation, and what it means to offer solutions and solidarity in the midst of a broken world. Her memoir offers an antidote to the distraction, indifference, and denial of our modern culture. “Perhaps the worst thing is not death,” she writes, “but the ways we cover up our own desire to express deep reverence for life.”

In short chapters that reflect on her happy childhood, her vocational path in food justice, and the tender family life that she and her husband built, Quinn explores how grief and joy accompany each other as we learn to live fully in our bodies and then learn to surrender them. Through descriptive prose she shares the beauty she finds everywhere, from the scent of the vegetable garden she tends to feed Nashvillians who are food insecure to the color of the wildflowers that will grow in the green burial ground she chooses as her final place of rest.

Her epiphanies do not mask the pain and confusion of her illness as Quinn describes the toll a brain tumor takes, dimming her sight and jumbling her thoughts so that she can no longer do simple things she loves without assistance: read, write, manage simple math or a coherent conversation. Someone is always there to assist her in the vulnerable moments — her husband to read the cards she receives, her father to edit her voice memos into chapters, her mother to steady her as she picks out a grave plot, her cousin to weave a burial shroud in the colors of a sunset, her 10-year-old daughter to take over cooking dinner, and a close friend to help her process what her young children need now versus what they will remember. What We Wish Were True is a love letter to life written as a dozen thank-you notes to the people, places, flora, and food that filled it.

Her epiphanies do not mask the pain and confusion of her illness as Quinn describes the toll a brain tumor takes, dimming her sight and jumbling her thoughts so that she can no longer do simple things she loves without assistance: read, write, manage simple math or a coherent conversation. Someone is always there to assist her in the vulnerable moments — her husband to read the cards she receives, her father to edit her voice memos into chapters, her mother to steady her as she picks out a grave plot, her cousin to weave a burial shroud in the colors of a sunset, her 10-year-old daughter to take over cooking dinner, and a close friend to help her process what her young children need now versus what they will remember. What We Wish Were True is a love letter to life written as a dozen thank-you notes to the people, places, flora, and food that filled it.

Quinn focuses on what she can do at each stage of her disease to be present to her life and her children. Once admired for her fabulous cooking, she does the mise en place — gathering and organizing the ingredients — for her daughter’s culinary training. She listens to Lulah’s plans and thanks her daughter that the family won’t exist on frozen pizza after she dies.

The preparation and the sharing of food serves as a source of revelation in so many of the stories in this memoir. On a church retreat, Quinn is given a secret “God-word” meant to describe how others see the way that divine love is embodied in her life. Recalling that the word was “bread,” Quinn recruits a colleague to make hundreds of loaves to be passed out at her funeral.

Quinn died in February of this year, but if the stories in this book are any evidence, she had enough time to consider how she wished to be remembered and to leave a trail of crumbs for her loved ones. Each short reflection feels like an ingredient Quinn has gathered and prepared for someone she loved, even the reader she will never meet. Together her words make more than a recipe for a good life; they’re an invitation to a great, unpredictable feast. No one can be sure how it will come together, only remain hopeful that it somehow will.

No part of an embodied life is guaranteed except for death. I think about everything I will miss, what I won’t be alive to witness or to experience or endure or to bounce back from. I think about specifics – no singing showtunes in the minivan. No burnt toast with butter in the mornings. No snuggling up to watch cooking shows. … Part of my focus on the future is my desire to make a smooth path for loved ones in a tangibly helpful way — printing family photos, revisiting our advanced directive documents, setting aside gifts to open on special occasions in the future, finally cleaning out the basement, and, I don’t know, ending misogyny in all forms!

After learning of Quinn’s diagnosis, a friend wishing to show her support brought fresh loaves of bread every week, reminding Quinn that the word “accompany (au con pain)” means “to come with bread.” What We Wish Were True savors the moments and morsels that sustain our lives even as it uncovers our limitations and the depths of our grief. There is not much we can do in the face of dying but show up for every moment in it and for each other — preferably with bread.

Beth Waltemath, a native of Nashville, is a writer, writing coach, and a minister. She currently lives in Decatur, Georgia. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Chapter 16.

Tagged: Book Reviews