The Joy of Science

Two noted scientists explain their job and why it matters

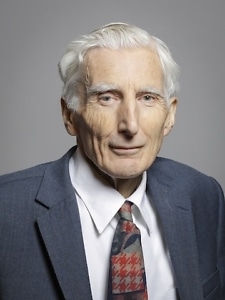

The Shape of Wonder by eminent scientists Alan Lightman and Martin Rees is an apology in the classical sense, meaning a reasoned defense of an idea. Sadly, the idea that the authors feel called upon to defend is that science can be trusted. The Shape of Wonder is Lightman and Rees’ attempt to counter the growing mistrust of scientific institutions around the world by helping readers “understand scientists as people and what they actually do, how they think, work, and live.”

The Shape of Wonder begins with two individuals: Alan Lightman’s two-year-old daughter delightedly seeing the ocean for the first time, and Lucile, a high school English teacher who wonders why scientists “always seem to be changing their minds.” The toddler and the teacher represent the two poles around which The Shape of Wonder is structured: the joy of scientific discovery versus skepticism about the means and ends of science.

Lightman and Rees begin by developing the concept of “disciplined wonder,” the trait they attribute to all scientists, regardless of field or time period. But neither discipline nor wonder is the province of scientists alone. “The capacity for wonder,” they write, “is part of our DNA.” The discipline they refer to is the scientific method, which “might better be called ‘critical thinking,’” and it is also utilized by “lawyers, doctors, auto mechanics, and accountants.” In a way, Lightman and Rees imply, we all have the capacity to be scientists.

The Shape of Wonder braids profiles of individual scientists, past and present, with chapters exploring the thought processes, motivations, and methods of discovery common to scientists across disciplines. Each profile outlines the scientist’s current research, relates their origin story — i.e., the roots of their passion for discovery — and describes their hobbies and family life. We learn that neuroscientist Lace Riggs overcame the challenges of growing up in a family plagued by “drug addiction, mental illness, and suicide.” Marta Zlatić, who works in optogenetics, draws strict boundaries between work and family life and says, “Weekends are just with the children.”

While the profiles demonstrate how much scientists have in common with the rest of us, the more general chapters examine the particular combination of traits that set them apart. For example, “independence of mind” is crucial, as are “objectivity and the banishment of emotion.” Personal attachment to their ideas could prevent scientists from investigating new evidence when it appears.

This lack of egotism can also be seen in how scientists think about their work. Instead of walking into a lab every day with the grandiose intention of curing cancer or launching a human mission to Mars, scientists “focus on a tiny piece of the puzzle and tackle something that seems tractable.” Finally, their job comes with a unique payoff: While everyone can appreciate the joy of learning something new, that joy may be greater for the scientist “because he or she may be the first person on the planet to understand some new property of the universe.”

Lightman and Rees conclude with proposals about how science might address the thorniest issues of our time, such as climate change, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology, and thus produce outcomes beneficial to humanity as a whole. They note that the success of their proposals is contingent upon scientists’ fulfillment of their ethical responsibilities, which include involving themselves in policy debates and communicating effectively with the public in the interpretation and presentation of data.

Lightman and Rees conclude with proposals about how science might address the thorniest issues of our time, such as climate change, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology, and thus produce outcomes beneficial to humanity as a whole. They note that the success of their proposals is contingent upon scientists’ fulfillment of their ethical responsibilities, which include involving themselves in policy debates and communicating effectively with the public in the interpretation and presentation of data.

The Shape of Wonder is itself an effort at effective communication. In pursuit of their goal of giving the public “enough of a feel for science to avoid becoming bamboozled by propaganda and bad statistics,” Lightman and Rees aim to reach a broad audience, including those who require an explanation of the scientific method and other basic principles. Beyond the deficits in many Americans’ science education, the authors must also contend with the rampant political polarization that encourages rejection of any evidence that contradicts one’s world view. Nonetheless, thanks to its lucid prose and humane approach to science, The Shape of Wonder will be a fascinating and enlightening read for anyone who maintains that fundamentally human trait of curiosity.

Whitney Bryant is a writer, teacher, and editor. Her work has appeared in The Georgia Review, One Story, and Shenandoah. A graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, she lives in Nashville.