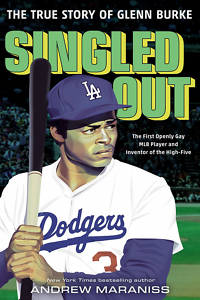

The Natural

Singled Out recounts the athletic feats and personal tragedies of baseball’s Glenn Burke

FROM THE CHAPTER 16 ARCHIVE: This review originally appeared on February 24, 2021

***

The title of Andrew Maraniss’ new book, Singled Out, captures the predicament that Glenn Burke faced in the 1970s. As a baseball player with an Adonis physique and extraordinary athletic gifts, Burke stood out even among his major league teammates. An extrovert with a colorful sense of humor, he offered entertainment in the locker room and leadership on the diamond.

What really made him different, though, was a secret he tried to conceal. By the time he reached the big leagues, Burke knew he was gay. Playing a sport that Maraniss describes as “the heart of homophobia,” Burke understood that staying in the closet was his only option. He led a double life for as long as he could — macho outfielder for the Los Angeles Dodgers by day, disco denizen by night — but soon rumors of his sexual orientation hastened his exit from the sport he loved.

Maraniss describes Burke as a magnetic individual with boundless charm. On bus rides, he sang along with music blaring from his boombox; he kept the dugout upbeat and engaged with constant streams of chatter. Decades later, journalist Lyle Spencer described him as “the most lively personality I ever covered in forty-five years in sports.” Typically the instigator of team celebrations, Burke was the first athlete to deliver a high five when he spontaneously rushed to greet Dusty Baker after Baker hit his 30th home run in the last game of the 1977 season.

Maraniss begins the story with Burke’s upbringing in Oakland, where his athletic legend began on the city’s blacktops. His friends recall his amazing jumping ability and ruthless competitiveness on the basketball court and his affability off of it. Burke “was the funniest kid in his circle of friends,” Maraniss writes, “adept at perfectly mimicking the popular Black comedians of the day.” His performance on the court, leading to high school championships, turned him into an East Bay celebrity who seemed destined for success.

To account for Burke’s experiences off the field, Maraniss covers cultural revolutions of the 1970s and 80s. Burke’s MLB debut in 1977 coincided with the explosion of disco, a milieu in which a gay Black man could experience freedom and a measure of equality. In the offseason, and whenever he could sneak away during the season, Burke raced to clubs and indulged in all available pleasures.

Out of consideration for his younger readers, Maraniss soft pedals the sex-and-drugs angle, but he makes it clear that Burke’s downfall was not the result of a random sexual hookup or occasional narcotic use. Burke approached partying, especially in the Castro district of San Francisco, the way he played sports: at full speed, with maximum effort and balletic grace. Burke was perfectly suited to the disco era. Former major league player Tito Fuentes compared Burke to “a glistening mirror ball at a discotheque when the light hits it and all of these different reflections and colors flash all over the room.”

Out of consideration for his younger readers, Maraniss soft pedals the sex-and-drugs angle, but he makes it clear that Burke’s downfall was not the result of a random sexual hookup or occasional narcotic use. Burke approached partying, especially in the Castro district of San Francisco, the way he played sports: at full speed, with maximum effort and balletic grace. Burke was perfectly suited to the disco era. Former major league player Tito Fuentes compared Burke to “a glistening mirror ball at a discotheque when the light hits it and all of these different reflections and colors flash all over the room.”

Maraniss offers a nuanced perspective on Burke’s relationships with his teammates. When spring training started, Burke left the expressive gay subculture and returned to the “repressive existence” of the Dodger locker room. With the team, he found joy on the field but struggled to fit into the players’ skirt-chasing lifestyle.

In the fishbowl of MLB, Burke’s hidden life became difficult to disguise. His teammates faced the dilemma of suppressing their suspicions or confronting Burke. In Los Angeles, clubhouse leaders Dusty Baker and Davey Lopes took different tacks. Baker felt compelled to learn the truth, so he talked to Burke and queried his friends, but no one gave a forthright answer. When Lopes heard the rumor, he thought about it briefly and then dismissed it as irrelevant. “You know what? I don’t give a shit,” Lopes told a teammate. “He was an integral part of the ball club.”

Maraniss deserves credit for giving proper space to Burke’s less savory traits. While still in the minors, Burke developed a “reputation as an unpredictable hothead” whose temper was often directed at authority figures. He was a poor judge of character, trusting friends who had proven to be selfish. His drug abuse, which skyrocketed when he was a well-paid baseball player, continued during the thin years that followed, ultimately landing him on the streets.

Singled Out is marketed as a young adult title — the author’s third, after Strong Inside and Games of Deception — but its content and language assume mature readers. Maraniss is unsparing about the vitriol suffered by Burke and other homosexuals, most egregiously when the AIDS epidemic caused the deaths of thousands. This book pays long-overdue tribute to a cultural pioneer, a man who wanted simply to play ball and dance in a world that was not yet ready for his moves.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.