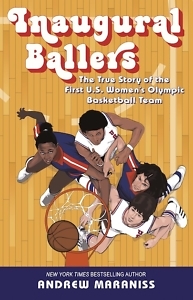

The Spirit of ‘76

Andrew Maraniss tells the story of a pioneering women’s basketball team

The title of Andrew Maraniss’ latest book, Inaugural Ballers, with its internal rhyme and fine balance of formal language and street argot, neatly captures the book’s two predominant narrative threads. Subtitled The True Story of the First US Women’s Olympic Basketball Team, the book describes the challenges faced by the trailblazing 1976 team to gain support and recognition in a sports landscape that overlooked the achievements of female athletes. While the men’s Olympic team traveled in comfort and enjoyed continual media coverage, the women practiced in obscure gyms and battled the perception, often exacerbated by newspaper columnists, that playing basketball made them “mannish.”

The “baller” half of the title is equally important. Maraniss knows the sport of basketball in its historical scope and gritty details. With the eye of an opposing coach, he offers succinct breakdowns of players’ strengths and weaknesses, and he recounts critical games like a seasoned reporter. His story takes you inside team practices, through the grueling qualification process — a path made more difficult by the team’s eighth-place finish in the 1975 World Championships — and onto the court for each game of the Olympics. When the team slips up, Maraniss explains why; when they succeed, he captures the rapturous quality of “perfect basketball.”

Having already written books for young adult readers on Perry Wallace, the Vanderbilt player who broke the color barrier in the Southeastern Conference (Strong Inside), and on the first men’s Olympic basketball team (Games of Deception), Maraniss is well suited to comment on the cultural significance of the 1976 women’s team. Women began playing organized basketball in the 1890s at Smith College, and in the pre-World War II era the sport was popular among women in certain regions. But by the 1950s, as Maraniss points out, “conservative social mores reinforced traditional gender roles”; as a result, “women’s basketball took another blow.”

Maraniss tracks the resurgence of women’s basketball in the 1960s and 70s alongside other sea changes in America, particularly the civil rights movement and second-wave feminism. At every step, women had to battle entrenched sexism and the complacency of athletic departments accustomed to treating women as second-class citizens. “When [Coach] Billie Moore’s team arrived in Montreal in the summer of 1976, they hadn’t just overcome a series of opponents on the basketball court to reach the game’s summit,” Maraniss writes, “they had climbed a mountain composed of nearly a century’s worth of misogyny and obstruction.”

Maraniss tracks the resurgence of women’s basketball in the 1960s and 70s alongside other sea changes in America, particularly the civil rights movement and second-wave feminism. At every step, women had to battle entrenched sexism and the complacency of athletic departments accustomed to treating women as second-class citizens. “When [Coach] Billie Moore’s team arrived in Montreal in the summer of 1976, they hadn’t just overcome a series of opponents on the basketball court to reach the game’s summit,” Maraniss writes, “they had climbed a mountain composed of nearly a century’s worth of misogyny and obstruction.”

An interesting pattern emerges as Maraniss pieces together the players and coaches who comprised the team. They came largely from small towns and regional colleges, not the major conferences that ruled men’s sports. The stars of women’s hoops came from schools like Immaculata College (which won three national titles while playing in skirts), Wayland Baptist, and Delta State. One of the team’s feistiest players, Pat Head, grew up in Ashland City, Tennessee, 25 miles from Nashville. Later known by her married name, Pat Summitt coached at the University of Tennessee for 38 years, becoming the all-time winningest collegiate coach and leading the Lady Vols to eight national championships.

One measure of the team’s legacy is that, on the heels of its success, big colleges quickly commandeered talent and attention away from the small-college vanguard. In the ensuing decades, “A girl in Tennessee wouldn’t go to UT Martin anymore,” as Pat Head had done; “she’d go to an SEC school like Vanderbilt or the University of Tennessee,” writes Maraniss, a ’92 Vanderbilt grad and long-time Nashville resident. “Gone were the bake sales and car washes; in came full scholarships and chartered planes.”

The ’76 Olympic team faced issues regarding race and sexuality that reflected the country’s burgeoning consciousness. Their conflicts also indicated how much work was left to be done. “For Black women growing up in the South during this period,” Maraniss observes, “broader social changes played out in the particularities of their daily lives and careers.” Black players such as Lusia Harris and Carolyn Bush and Assistant Coach Bessie Stockard made signal contributions to the team; still, the perception lingered that racism, perhaps even a Black quota, factored into there being only four Black players on the Olympic roster.

Every woman on the team had long contended with the stereotype that girls who played basketball “must be gay.” Ann Meyers, who became “the first woman to receive a full athletic scholarship at UCLA,” was accused of being gay at a time when she didn’t understand the term. “In burdening a young basketball player with their homophobic presumptions, Meyers’ classmates and their parents were thrusting her squarely into the middle of a hackneyed conversation,” Maraniss writes.

Coach Moore told the team that their performance in the Games “will change women’s basketball for the next twenty-five years.” Moore’s bold prediction turned out to be an understatement: Her “inaugural ballers” started a revolution whose aftershocks continue to reverberate today.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.