The State of the Workers

An Arkansas journalist reveals hard truths about the food industry

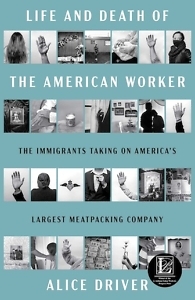

Sorry, but there is no way to tell you about Alice Driver’s Life and Death of the American Worker: The Immigrants Taking on America’s Largest Meatpacking Company without disgusting you.

Here’s what Victor, a machine operator at Tyson Food’s Chick-N-Quick plant in Rogers, Arkansas, has to say about the ingredients in chicken nuggets, according to the book: “All the waste from the debone area, the skeleton, the skin, the neck, the hip bone — all of that is ground up to make nuggets which have almost no meat in them.”

There is chicken in there, but according to Victor, whose real identity is protected by Driver, we’re not talking about top-grade meat. “Many times, the chicken is rotten,” Victor says. “It smells. It arrives like a rock. When we open it, it is already a different color, not pink. It is green or purple.”

Driver, a native of Arkansas, is a journalist and translator who writes about migration, human rights, and gender equality. Her book tells more disturbing stories about the immigrants Tyson puts to work making their products, how Arkansas politicians including the Clintons have carried Tyson’s water, and the health hazards in their meatpacking plants. Driver includes brutal anecdotes about a chemical spill that damaged the breathing of Tyson employees without any immediate consequences for the company and repetitive stress injuries to workers from doing the same motions for years at a time deboning chickens.

More broadly, Life and Death of the American Worker documents what happens when the power in an employer/worker relationship is very one-sided.

Alice Driver spoke with Chapter 16 ahead of her appearance at the 2024 Southern Festival of Books. The discussion has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Chapter 16: In the book, you state that “workers at plants like Tyson are immigrants and refugees from all over the world, citizens and undocumented, literate and illiterate — making it harder for them to organize and band together.” Given that, how were you able to gain the cooperation of Tyson workers for your research?

Alice Driver: They were more afraid [during COVID-19] of dying than of being fired. Also, I speak fluent Spanish. You absolutely cannot tell these stories without speaking another language. … Like the Karen workers [from the border region of Myanmar and Thailand], I only did a few interviews [with them] because it was impossible for me to get a Karen translator in Arkansas. … So I decided, okay, I’m working with Spanish-speaking workers because that is what I can do on my own. I didn’t have a translation budget. I was working on a shoestring, and it was just very complicated.

Chapter 16: Are you concerned that Tyson might find a way to come after you legally?

Driver: Well, the wonderful thing is that my publisher did a fact check. Simon & Schuster and I got a pro bono legal review from Cornell Law School. … Do I worry about being sued? I worry because I’m in Arkansas [where Tyson is based]. It is a vulnerable place to be, but I have done everything in my power and had so much support from a really strong team at Simon & Schuster.

Chapter 16: Why were you attracted to Tyson and the meatpacking industry as a story?

Driver: I’m from rural Arkansas. I’m from the Ozark Mountains, and there is a Tyson plant about 45 minutes from where I grew up. I grew up in a town of 200 and a lot of people in that town worked at Tyson, so I grew up with chicken houses around and following Tyson trucks full of chickens. … Some of the first immigrants I met were Tyson workers.

Driver: I’m from rural Arkansas. I’m from the Ozark Mountains, and there is a Tyson plant about 45 minutes from where I grew up. I grew up in a town of 200 and a lot of people in that town worked at Tyson, so I grew up with chicken houses around and following Tyson trucks full of chickens. … Some of the first immigrants I met were Tyson workers.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, I was based in Mexico City and I just knew, like immediately, that [Tyson] workers were going to become infected in great numbers because anybody who knows how meatpacking plant lines are run, to keep production up, you can’t social distance. I applied for funding from National Geographic, and I got the funding to do the project. So that was the beginning. It was just going to be an article.

Chapter 16: A lot of the stories in the book are depressing. Was it difficult to report and write the book?

Driver: It was very difficult. It’s heartbreaking. I followed a group of workers for four years. Some of them died. Many of them got COVID. … In one case, nobody claimed the body of a worker who died because everybody was sick with COVID. It’s the most challenging project I’ve ever done.

Chapter 16: It must be rewarding to give these workers a voice since it’s become commonplace to demonize immigrants.

Driver: The main point of my book was looking at meatpacking and agricultural workers. These are the people who are upholding the food system in the United States. Many of them are undocumented. Many of them are immigrants or refugees, and they are doing absolutely backbreaking work. Meatpacking is one of the most dangerous jobs you can have in the United States, so I wanted to look at the dissonance between all of this discourse about how immigrants are flooding into our country. The reality is that all of these major companies — my focus is Tyson — absolutely rely on these workers, and we rely on them for the food that arrives to our table. I wanted to look at the strength and the moral beauty of these workers because that’s the conversation we should be having.

Chapter 16: Does it matter to meatpacking workers who wins the U.S. presidential election?

Driver: The meatpacking lobby, they give money indiscriminately. They supported Clinton, they supported Bush, so they’re going to support whoever wins. But does it matter if Trump wins? Absolutely, because as I recount in my book, at the height of the pandemic when people were getting COVID and dying and it was spreading throughout meatpacking companies like wildfire, there was an opportunity to say we should shut down plants. We should do contact tracing. We should take care of these workers. We should ensure there’s social distancing if we are going to keep [the plants] open. What happened instead was that the major meatpacking companies, Tyson included, met with the Department of Agriculture. They had discussions with Vice President Pence, and right after they did that, Trump declared that all [meatpacking] facilities had to stay open because it was necessary to provide food for the United States. In reality, meatpacking companies were exporting a lot of their meat anyway, so it wasn’t really an issue of domestic production. It was an issue of profit.

Chapter 16: You also show that racism is rampant in this system in the relationship of Tyson to prison labor. Would you explain?

Driver: Arkansas has a long history of deeply rooted racism. … I found out that Tyson buys corn from an Arkansas prison, which is at the site of a [former] plantation. Black people only make up a small percent of the Arkansas population. They’re a large percent of the prison population, and they are growing the corn for zero dollars that Tyson buys from the prison system. So all these ways that they’re saving money are really rooted in racism.

Chapter 16: Is the solution unionization?

Driver: We need more oversight. We need unions. We need support for workers who don’t speak English and often have no translator at work.

Chapter 16: You don’t spend much time in the book on the Tyson family. Why?

Driver: I include some descriptions of the members of the family, like Don Tyson. Being from Arkansas, [I know] the parties he threw were epic. His motto, which he said all the time, was “Life is too short not to have a good time.” [The Tyson family] have houses all over. They go to Cabo. They have a huge art collection. I want to contrast that with the state of the workers.

Jim Patterson is a freelance writer in Nashville. His work appears regularly on the United Methodist News website, UM News. He formerly covered country music for the Associated Press and was a public affairs officer and senior writer at Vanderbilt University.