The Stories of Emmett Till

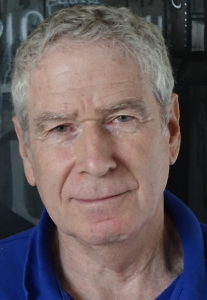

Historian Elliott Gorn sifts through the myths of a tragic American murder

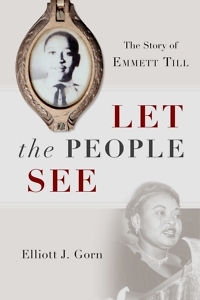

We keep telling the story of Emmett Till. His murder, which happened in Mississippi in 1955, is sometimes called the beginning of the modern civil-rights movement. Yet we also keep learning what actually happened, and we keep giving it new meanings. In Let the People See: The Story of Emmett Till, Elliott Gorn combines a riveting story with a smart analysis of its evolving significance.

Gorn is the Joseph Gagliano Professor of American Urban History at Loyola University of Chicago and the author of numerous celebrated books, including Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America, Dillinger’s Wild Ride: The Year That Made America’s Public Enemy Number One, and The Manly Art: Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting in America. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Gorn is the Joseph Gagliano Professor of American Urban History at Loyola University of Chicago and the author of numerous celebrated books, including Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America, Dillinger’s Wild Ride: The Year That Made America’s Public Enemy Number One, and The Manly Art: Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting in America. He answered questions via email from Chapter 16:

Chapter 16: The murder of Emmett Till is a central event of the modern civil-rights movement, yet the details of the actual crime remain a source of controversy. What do we know? What don’t we know?

Elliott Gorn: The Till murder was like an American Rashomon. The stories about his murder were so conflicting. That doesn’t mean that all “facts” are equal—far from it. A Mississippi jury tried two men, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, and found them innocent with only an hour of deliberation. They confessed a few months later to Look magazine in exchange for money. As an FBI investigation revealed ten years ago, a handful of their friends and relatives were also involved, though in exactly what capacity is unclear. In addition, two or three African-American men who worked for Milam were compelled to assist in transporting Till.

Even the role of Carolyn Bryant is a little unclear. On the witness stand, she accused Till of grabbing her in a way that threatened rape. But that’s not how she described their encounter two weeks earlier. The obfuscation continues. Last year historian Tim Tyson wrote that Bryant confessed to him that whatever Till did to her, he didn’t deserve to die. Now she denies ever saying that. The whole case was like that. It often still is.

It sometimes feels like the public is looking for a big “reveal,” that, say, scores of Klansmen killed Emmett Till. It didn’t happen that way, and in a sense it was worse. Politicians, editors, and the wealthy members of the Citizens Councils empowered men like Milam and Bryant and their kin with racist rhetoric, with calls of segregation forever.

Chapter 16: What were the legal strategies during the September 1955 trial of J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant in Sumner, Mississippi? Why did the jury render the verdict of “not guilty”?

Gorn: The trial really is central to understanding this tragedy. Judge Curtis Swango was a very fair and honest man, and the prosecutor, Gerald Chatham, worked hard for a conviction. But they were up against the built-in prejudices of an all-male, all-white Mississippi jury. And the jury was constituted that way because blacks couldn’t vote in Tallahatchie County (though they made up two-thirds of the population), and women were not allowed to serve either. No Mississippi jury ever convicted white men of killing a black person, and it wasn’t going to happen this time.

The prosecution had a good circumstantial case, including the defendants’ confessions that they kidnapped Till. The defense worked two angles—Till was guilty of sexual assault, and, contradictorily, the body found in the river wasn’t Emmett Till, as there was no evidence that he was really dead. Pretty lame, but good enough for the jury in Sumner, Mississippi. Unsaid was what really mattered: the accusation that a black man had assaulted a white woman. If you convict Milam and Bryant, one defense attorney said in his closing remarks, your Anglo-Saxon ancestors will turn over in their graves.

Chapter 16: “Months after the trial,” you write, “Americans kept relitigating the case, probing its meanings, interpreting its significance.” What were the different ways that Americans of the 1950s understood the murder of Emmett Till?

Chapter 16: “Months after the trial,” you write, “Americans kept relitigating the case, probing its meanings, interpreting its significance.” What were the different ways that Americans of the 1950s understood the murder of Emmett Till?

Gorn: It is amazing how many prominent Americans had something to say about the case. William Faulkner wrote about it multiple times. Rod Serling (creator of The Twlight Zone) wrote a couple of screenplays for television based on the Till story. People like Congressman John Lewis, Rosa Parks, and future heavyweight champ Muhammad Ali later described how the case weighed on them.

For months, African Americans north and south organized Emmett Till rallies that brought out tens of thousands of citizens. The FBI looked for communists and other subversives, while the United States Information Agency did everything it could to make the verdict seem like a mere aberration of American democracy. Jim Crow’s defenders extolled the victory of Southern justice, and Northern racists working to keep neighborhoods segregated did likewise. Four months after the trial, journalist William Bradford Huie wrote a very influential article for Look magazine, in which he paid for Milam and Bryant’s confessions of guilt, while depicting Till as the white South’s worst enemy, an aggressive and defiant black man who insisted to the end on his right to “have” white women.

Chapter 16: Emmett Till’s parents, Mamie Till Bradley and Louis Till, play central roles in this political drama, though in very different ways. How did each shape the narrative of their son?

Gorn: Louis Till was a violent man. Shortly after Emmett was born, he assaulted his wife, Mamie, and she finally got a court order to keep him away. When he violated it, a judge told him to choose jail or the army. He took the latter, and in 1942, he was shipped out to Italy to work as a stevedore. Near the end of the war, he was court martialed for murder and rape, and the U.S. Army hanged him just after the war in Europe ended. Army documents are not conclusive. It was a reasonably strong case, though a good defense attorney in a civilian court well might have prevailed. But this was the Army, where African-American soldiers were prosecuted, especially for sex crimes, way out of proportion to their numbers.

Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Till Bradley, had a long life in Chicago. She famously insisted that her son be buried with an open coffin, and she allowed photos of his mangled face to be printed. Mainstream newspapers and TV wouldn’t touch those images, but they circulated freely among African Americans in Jet magazine and newspapers like The Chicago Defender. The impact was electric.

One or two hundred thousand people came to Emmett Till’s funeral, and millions of black Americans saw his photo. For months, rallies in American cities attracted thousands and thousands of outraged citizens. Mamie Till Bradley addressed these Emmett Till rallies, demanding justice, including new civil- and voting-rights legislation. These were preludes to the mass protests of the 1960s. In coming years, Mamie Till Bradley became a beloved Chicago teacher who continued to tell her son’s story as a way to preach against racism.

Chapter 16: The fourth and final section of Let the People See, called “Memory,” explores the meaning of Emmett Till in the half-century after his death. How did the way we tell his story evolve over time?

Gorn: The Emmett Till story is so well-known today that people assume it has been so since 1955. The New Yorker and Time magazine, for example, recently repeated, incorrectly, that the photos of Emmett in his coffin were widely distributed right after his death, and that they changed the hearts of many whites. This is simply not true. Very, very few whites saw those photos in 1955; news media, too, was segregated. Moreover, the “Emmett Till Generation” of African-American activists kept his memory alive, but virtually none of the press noted the twenty-fifty anniversary of his passing.

This began to change when the celebrated documentary of the civil-rights movement, Eyes on the Prize, began its story with the Till murder. For the first time, in that film, Mamie Till Bradley’s words, “Let the people see what they did to my boy,” came true for both black and white Americans. Only by the twenty-first century did the faces of Emmett Till—the happy pictures taken the Christmas before his murder and his death photos—become the very icons of racism in America, of hatred, brutality, and injustice.

The story has only grown since then, with books, documentaries, oral histories. As more Americans reject sugar-coated history and desire the hard story of our racist past, the Till saga—of a young boy from the north who just didn’t understand the racial codes of the world he’d descended into—has become one of the central tales of the madness and cruelty of American racism.

Chapter 16: How does Emmett Till remain a political touchstone today? How we do we keep shaping his memory?

Gorn: If you go back and look at the newspaper coverage of recent slayings of young black men by law enforcement officials over the past five years, you’ll notice that since Trayvon Martin, over and over again the stories begin by invoking Emmett Till’s name. Referring to such shootings, Oprah Winfrey said the police killings are like a new Emmett Till every week. The Till story has become shorthand for the failure of the law to bring justice to minorities. He is part of Black Lives Matter.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.