The Way He Works

David Macaulay talks with Chapter 16 about a career built on curiosity

Twenty-five years ago and long B.G. (before Google), illustrator and writer David Macaulay published his groundbreaking book, The Way Things Work, now a classic of children’s nonfiction. There had truly been nothing like it: hundreds of meticulously illustrated pages demystifying the inner workings, and physics and mechanics, of everything from keys and locks and can openers to steam engines and nuclear power and movie cameras and telescopes to GPS and flight simulators, and seemingly every manmade invention or system (supermarkets! airlines!) in between. In a whimsical, playful stroke, a wooly mammoth plays a supporting role through the book, aiding in the show-and-tell.

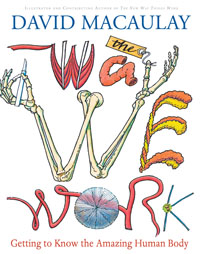

This fascinating compendium became a home-library staple for a generation of young readers, as did Macaulay’s follow-up in 2008, The Way We Work—an equally exhaustive and assiduously researched project on the human body. The popular success and critical acclaim of both volumes—not to mention Macaulay’s many other highly regarded illustrated books for children (one, Black and White, won the Caldecott Medal in 1991; another, Cathedral, was named a Caldecott Honor book)—have secured Macaulay’s standing in the halls of great children’s literature. In 2006, he was awarded the prestigious “genius grant” by the MacArthur Foundation, which noted that his “visually arresting and thought-provoking body of work invites readers of every age to perceive the world they occupy from surprising and compelling perspectives.”

This fascinating compendium became a home-library staple for a generation of young readers, as did Macaulay’s follow-up in 2008, The Way We Work—an equally exhaustive and assiduously researched project on the human body. The popular success and critical acclaim of both volumes—not to mention Macaulay’s many other highly regarded illustrated books for children (one, Black and White, won the Caldecott Medal in 1991; another, Cathedral, was named a Caldecott Honor book)—have secured Macaulay’s standing in the halls of great children’s literature. In 2006, he was awarded the prestigious “genius grant” by the MacArthur Foundation, which noted that his “visually arresting and thought-provoking body of work invites readers of every age to perceive the world they occupy from surprising and compelling perspectives.”

Macaulay’s books, accessible and complex at once, are decidedly not just an enjoyable learning resource for the inquisitive elementary school set. Few artists have achieved an equivalent cross-generational appeal. A quick scroll through a Metafilter community page devoted to Macaulay provides testament to his work’s impact and endurance. His books are made for revisiting, designed never to be grown out of: “Every once in a while I take down the copy of The Way Things Work that I got from my parents when I was a wee nerdling,” one online fan writes. “Unbuilding was one of my favorite books as a kid,” another comments. “Kind of makes me wonder why I haven’t exposed my (almost) five-year-old to Macaulay yet.”

Indeed, a generation that came of age with Macaulay’s bestselling creations is now raising its own brood, which may mean that gears are primed for a cyclical celebrating and revisiting of his oeuvre—not that it has ever slipped into obscurity. (The Way Things Work, which also spawned a popular PBS series of the same name, was updated in 1998 as The New Way Things Work.) Meanwhile, Macaulay continues to train young artists at the Rhode Island School of Design, his alma mater, where he’s been a longtime faculty member. Watkins College of Art, Design & Film will present him with an honorary doctor of fine arts degree at the college’s commencement ceremony on May 18. Prior to his appearance, Macaulay answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Do you remember the very first thing—machine, gadget, toy, or otherwise—that you took apart and examined closely?

David Macaulay: We didn’t actually have things to “take apart.” We had some leftover cardboard and that brown-paper packing tape that you licked and it tasted awful. We also had wooden spools left over from my mother’s sewing. I made things out of this stuff—a train signal standing next to a bit of train track, an elevator in a shoebox. Whatever I made had to work. You pulled a piece of sewing thread that ran under the sticky-tape tracks, and it moved the signal up or down. I didn’t have a train, so working the finished product wasn’t all that exciting. The pleasure came from figuring out how to make it in the first place.

Chapter 16: Working on The Way We Work required you to do lots of interesting, in-depth medical research. What dispatches from the frontiers of science have held your fascination lately?

Chapter 16: Working on The Way We Work required you to do lots of interesting, in-depth medical research. What dispatches from the frontiers of science have held your fascination lately?

Macaulay: One of the advantages of being able to compartmentalize (or of having a short attention span, depending on your point of view) is that I tend not to carry things with me from one book to the next. Once the body book was done, it was done. I know a lot more now about how my body works (which was the whole point), but I don’t think about it much because I’m on to the next completely unrelated project. So I don’t pay much attention to whatever is going on in medical research or discovery. If something really significant happens, I’ll hear about it somehow. The only frontiers that really matter to me are the next project and how can I make a better book and learn about something new (to me). It’s a very self-indulgent way to make a living.

Chapter 16: As I’ve prepared these questions, I’ve watched a spider crawl down the wall behind my desk, amble across a USB cord and some papers, and then lower itself to the floor from the desk’s edge by its silk. Which makes me think, of course, of the incredible architecture of animals, insects, and plants. If you were to explore the natural world as you have that of built environments and the human body, where might you be most likely to start?

Macaulay: At this point, the natural world is literally and figuratively a whole can of worms I’ve sort of side-stepped. With the exception of human anatomy, which happens to be the kind I’m equipped with and therefore felt compelled to better understand, I find myself drawn more to better understanding the things we humans create and why.

Chapter 16: How did winning a MacArthur Fellowship change things for you?

Macaulay: It didn’t change anything. It paid the bills, and that allowed me to keep doing what I was doing, in this case studying human anatomy. Had I not been working on that book, I might have used some portion of it to explore something new. But in reality, I love what I do, and I pick things to learn about that interest me and that I think might, if presented in the best way, interest others. I had no desire to change direction because in terms of content it keeps changing anyway.

Chapter 16: Planned obsolescence is nothing new, but it seems that we live in a world where we’re discouraged by manufacturers from dismantling, or attempting to repair, the small machines and technological devices we use. But at the same time, do-it-yourself culture is thriving; people are increasingly interested in things that are handmade and in making things for themselves. What do you make of the relationship between these two facets of twenty-first-century life?

Macaulay: The workings of technology upon which we allow ourselves to depend these days are increasingly invisible. You can’t watch an electron do what it does; you can’t sit down with a cup of coffee and watch a microchip work as you might an ant or spider, for instance. You can see and often enjoy the results of what technology does, but the “how it works” part remains a mystery. The scale of the workings of so much of what surrounds us disinvites casual curiosity. We aren’t encouraged to ask questions, and this is a problem. If curiosity isn’t encouraged at all levels, how are we to learn anything?

You can’t learn if you don’t ask questions, and you won’t ask questions unless something attracts your attention in the first place. At one time you could crank a lever, rotate gears, tighten a spring, and for some period of time “know” the minutes and hours of your day. Now we read a number on a cell phone. We no longer have the advantage of some visually accessible mechanism—some Rube Goldberg contraption—to make time seem a little less abstract.

It’s hardly surprising then, that we are drawn to the handmade. There are convenient limits to the scale of things we can make with our hands–both big and particularly small. There is a process which must be worked out and followed to make these things, a process which we can then apply and adapt to other problems we might encounter. Through this process we are being reconnected to our world. All our senses are engaged when we make things with our hands: materials are discovered and rediscovered, skills are developed and perfected, things are made that didn’t previously exist, and we are responsible. The satisfaction of even simple personal accomplishments has great meaning. It reminds us of our humanity, of our limits and of our potential.

Chapter 16: Accessibility is a word that comes up frequently in discussions of your work and what it achieves, what you hope for it. “I don’t think I’m very different from my readers in that I can get excited about something if it matters to me and if it is made accessible to me,” you once said in an interview. Is accessibility something you emphasize in preparing your students for careers in visual media?

Macaulay: One of the great pleasures of my work has been to meet people who are passionate about what they know and are willing to share that passion with me so I can pass it on to others. Through their patience and generosity, they make their knowledge accessible to me. The least I can do in my books is try to insure that my understanding and interpretation of what I have learned is made as accessible as possible to my readers. This is always the goal, and finding ways of achieving accessibility is always the challenge.

On May 18 at 2 p.m., David Macaulay will deliver the commencement address to the 2013 graduating class of Watkins College of Art, Design & Film in Nashville. The event, which will be held at the Downtown Presbyterian Church, is free and open to the public.