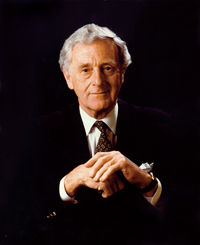

The Wisest, and Justest, and Best

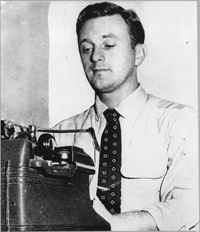

Novelist John Pritchard remembers the great journalist John Seigenthaler

John Seigenthaler, who died last year on July 11, was perhaps the most central and admirable personality that defined the Nashville I lived in during the 1970s. He was the apotheosis of integrity and of all that was serious and good. Anybody who knew him, even if they were his political opposites, held him in lofty esteem for the moral, thoughtful, and inspiringly intelligent human being he was. Indeed, John’s personal and professional record was well known.

He and I were by no means close friends, but we each had close friends who were close friends to both of us. To John I was merely a familiar face and a good acquaintance, while he, in the geist and gestalt of that time and place, was a major figure in Nashville, and I was bumbling about in the thick of it there. I lived in Nashville from the summer of 1970 until February of 1981, during my thirties and early forties. Like Memphis, Nashville was, in a social sense, a very small community. Everyone knew or knew about everyone else in all the odd and colorful corners of the city—in politics, Music Row, its huge academic community, downtown’s exceedingly high finance, late-night parties on Belle Meade Boulevard—it didn’t matter, anyone could be everywhere. Plus, everyone was connected or outright related, either on purpose or accidentally. I loved it all, and for a long time life there was electric.

He and I were by no means close friends, but we each had close friends who were close friends to both of us. To John I was merely a familiar face and a good acquaintance, while he, in the geist and gestalt of that time and place, was a major figure in Nashville, and I was bumbling about in the thick of it there. I lived in Nashville from the summer of 1970 until February of 1981, during my thirties and early forties. Like Memphis, Nashville was, in a social sense, a very small community. Everyone knew or knew about everyone else in all the odd and colorful corners of the city—in politics, Music Row, its huge academic community, downtown’s exceedingly high finance, late-night parties on Belle Meade Boulevard—it didn’t matter, anyone could be everywhere. Plus, everyone was connected or outright related, either on purpose or accidentally. I loved it all, and for a long time life there was electric.

I taught school. I waited tables. I lucked up and landed a momentary part as an on-camera-double for James Hampton in a Burt Reynolds film, W.W. and The Dixie Dance Kings, and I failed an audition at Opryland. (They asked me if I could sing and dance, and I said, “No, but I will.”) Yet most of all I learned how to write songs on Music Row, primarily in and around Ray Stevens’s Ahab Music, on Grand Avenue, and later over on 17th as a member of Tree International’s stable of ninety or a hundred other writers. By writing lyrics for pop and country songs, I learned more on Music Row about a writer’s craft than at any other time or in any other place. All the principles involved in putting together a country song are exactly the same principles one applies in writing a short story or a novel. In any case, back then I was struggling to make a living.

Somehow John Seigenthaler was aware of my efforts, and one day in the summer of 1972 when I was waiting tables down on Elliston Place at the Ritz Cafe, John, who was eating lunch there with several others, called me aside and offered me a part-time job as a copy editor at the Tennessean. I had recently written and sold two feature pieces to the Tennessean, but I don’t think that had anything to do with John’s momentary life-saving offer, which I gratefully accepted.

I lasted less than a month on the rim but produced what I have always thought was a dynamite headline—Smyrna Mayor Steers State Auto Group. However, because I was not adept in the math of making heads fit their space, my masterpiece broke and did not run.

I lasted less than a month on the rim but produced what I have always thought was a dynamite headline—Smyrna Mayor Steers State Auto Group. However, because I was not adept in the math of making heads fit their space, my masterpiece broke and did not run.

A few years later I had two full-time jobs—one as an English instructor and another as a Metropolitan Deputy Sheriff for Nashville and Davidson County. As an English instructor I was employed by the Dominican nuns, who adored John, and as a deputy I worked for Fate Thomas, Nashville’s High Sheriff, who was John’s boyhood friend and a fellow Democrat. I didn’t get hired by either of those two entities because of John; I mention him only to illustrate my claim that everything in Nashville was in fact linked through an infinite number of hooks and eyes. Anyhow, there I was, flanked by two enormous archetypes: working for Mother Superior on one hand and on the other for Father Fate!

The most direct reason I got the job as deputy was that Sheriff Fate Thomas had decided he wanted to go to college to earn at least an associate’s degree, and he was my student. He often failed to show up and would send one of his deputies to sit in class with a recorder and take notes instead. Fate performed remarkably well in Sophomore Lit—later I discovered that everyone in the sheriff’s office had played a role in writing Fate’s papers. But it was during that time that Fate told me he knew I needed extra employment and wondered if I would like to work for him as a deputy.

“Will I have a badge?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said.

I couldn’t wait to report for duty. I got the badge and was, like all my fellow deputies, forbidden to arrest anyone, ever, under any circumstances, no matter what. That sort of enforcement was the job of the Nashville Police. As deputies we did a thousand other things, and most of us, me included, “went armed” only when one or more of our county inmates escaped, which could mean they simply walked away with the visitors and went home. Whenever “an escape” happened, we deputies would “surround the house.” Bear in mind that most of us were teachers, coaches, recently unemployed young people, and one of our number was the drummer in the band on Hee Haw. But in those days in Nashville, if you were a Catholic or a Democrat—or even knew any Catholics and Democrats—you could be a deputy. And I was fortunate beyond words and in every direction.

Suddenly it was 2005. Twenty-four years had passed since the days of those experiences, and I found myself sitting with John in a studio at Nashville Public Television, taping a segment for his long-running program, A Word on Words. He was asking me about my first novel, Junior Ray, and saying wonderful things about the book, which was dubbed “hilariously tasteless” by Publishers Weekly and called, in the Mobile Press Register, “perhaps” the most profane literary work in recent history. (Both of those comments, I must add, were first-rate accolades.)

Suddenly it was 2005. Twenty-four years had passed since the days of those experiences, and I found myself sitting with John in a studio at Nashville Public Television, taping a segment for his long-running program, A Word on Words. He was asking me about my first novel, Junior Ray, and saying wonderful things about the book, which was dubbed “hilariously tasteless” by Publishers Weekly and called, in the Mobile Press Register, “perhaps” the most profane literary work in recent history. (Both of those comments, I must add, were first-rate accolades.)

John, however, was the first of only a very few individuals who have taken notice of the non-profane parts of Junior Ray, specifically the poetry that makes up much of “The Notes of Leland Shaw.” I have to say, not as hyperbole but as fact, that if John Seigenthaler had been the only one who ever asked me anything at all about my book, that would have been sufficient for the rest of my life.

Then, in December 2013, less than an Augenblick and thirty-two years after those Nashville “salad” days of “cakes and ale,” I was once again with John for A Word on Words at NPT, and I got my picture taken with Doris Kearns Goodwin and Ricky Skaggs—talk about covering the proverbial waterfront! This time John would be interviewing me about my third novel, Sailing to Alluvium. I was almost seventy-six, and John was ten years older. And on that crepuscular occasion and a long time before the cameras rolled, he and I spoke together about those far-away days and especially about Fate. We laughed a lot, particularly over a moment one night in Sperry’s Restaurant. I saw John at a table, and I went across the room to speak to him. He was smiling and said, “I was in Washington, and the FBI told me they think Fate is involved in organized crime. Do you think Fate is involved in organized crime?”

“Well, if he is,” I said, “it’s the end of organized crime.” The humor was automatic and explosive, and I shall remember the exchange even if my brain should shrink to the size of a Chiclet.

John Seigenthaler led a life that gives current meaning to everything Benjamin Jowett saw when he translated that last line in the “The Death of Socrates” from Greek to English: “Such was the end, Echecrates, of our friend, whom I may truly call the wisest, and justest, and best of all the men whom I have ever known.”

John Pritchard is the author of three novels: Junior Ray, The Yazoo Blues, and Sailing to Alluvium. He lives in Memphis. This essay is a lightly edited version of a piece that appeared originally at the blog of NewSouth Books.