The Word Is “Evocative”

A ponderous great book becomes a portal to the past

“Ever curl up with a good dictionary?”

George Carlin used to ask that question, or a version of it, at the beginning of one of his routines about words. Carlin loved words and the often humorous or, in his view, outrageous ways they were used. He riffed on oxymorons, euphemisms, simple absurdities, and, most famously, the seven words that couldn’t be said on TV because they would “warp your mind, curve your spine, and keep America from winning the war.”

Carlin’s way with words, his delight in their quirks, resonated with me and made him one of my favorite comics. And when he asked if I’d ever curled up with a good dictionary, I could immediately reply, “Yes.” Except that in my house, in those analog days before personal computers pushed the printed page to second-class status, the dictionary of record was not the sort of thing that encouraged curling, nestling, or any other cozy-sounding verb associated with words like “wingback chair” or “fireplace.”

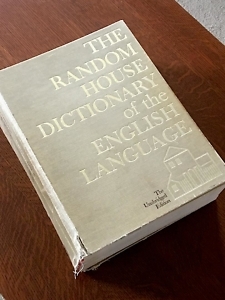

The Random House Dictionary of the English Language: The Unabridged Edition (1966) is a ponderous great book. Doorstop, a word often used to describe works of Tolstoy or Stephen King, fails in the presence of a book the dimensions of The Random House. Its size and weight more resemble a monk-illuminated Bible than a modern reference work. By actual measure on a bathroom scale, it weighs 9.4 pounds and occupies approximately 600 cubic inches of volume on whatever bookshelf is unfortunate enough to bear the burden of it. The only logical place to interact with such great mass is a large table or, in the preferred location of my youth, the living room floor.

I was just beginning my formal education when my father brought The Random House into our world, ideal timing for my introduction to the depth of our glorious language. It was not the only dictionary in the house — my brother and sister, both years older than I, had already won their own in spelling bees sponsored by The Detroit News — but it was the most authoritative. In any disagreement over spelling or definition, the big book was the final word. Webster’s might have had the edge in worldwide status, but in our family, it was The Random House that mattered.

The book resided on the bottom shelf of the built-ins to the right of the fireplace. Those shelves were Dad’s. Military history, science, and the reference sections of our home library were there, behind the chair in which he sat to read and do acrostics. Mom’s books were to the left of the fireplace, where one could browse volumes of American history, gardening, antiques, and birds. I naturally gravitated to Dad’s side, where the Time-Life Nature Library was the big draw (what little kid could resist The Reptiles?), but The Random House got its share of attention.

I would drag the dictionary off the shelf, haul it to the area in front of Dad’s chair, not far from the hearth, and plunk it down. Kneeling or prone I could then properly explore its bulk. Winter evenings, those long, dark stretches of time when boyhood rambunctiousness had little outlet, were the best for such intellectual pursuits. But I’m sure more than one rainy summer afternoon found me similarly engaged.

That first edition of The Random House Unabridged contains about 300,000 entries. Also included are abridged English-Italian, English-Spanish, English-French, and English-German dictionaries, a gazetteer, a world atlas, English usage and pronunciation guides, and various other bits of useful stuff. In all, 2,091 thumb-indexed pages. All of this seemed like most of the world’s knowledge to a young me, and flipping through it while lying on the short-napped, striped carpet was, if not my favorite pastime, at least a worthwhile one.

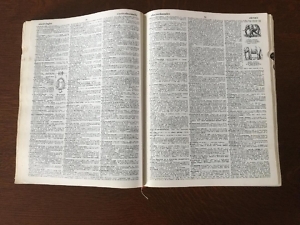

There are three columns of words on each page of The Random House, presenting a daunting list through which to search. But those long streams of entries are broken here and there by one of the most endearing aspects of the book: the illustrations. Open it at random and nearly every pair of facing pages will contain at least one, and usually several, little pen-and-ink drawings illustrating some definition. These drawings could be an attraction in themselves. What young boy, interested in all things animal, could resist looking up “elephant” and not be delighted to find both species of his favorite beast, the African and the Indian, in black and white?

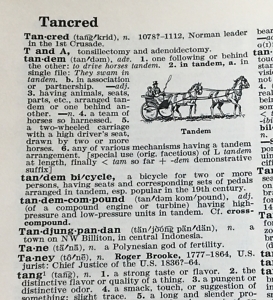

In my later years I have wondered which editors of this massive tome, the first dictionary to be assembled with the help of a computer, got to choose the words worthy of illustration. Why, for example, would page 1,452 include an illustration of a “tandem” horse team instead of a “tangent,” an important concept in geometry? There must have been some interesting discussions in the Random House offices during the years of editing that dictionary.

Novelist Kurt Vonnegut, who was not listed in the 1966 edition, wrote an essay for The New York Times, published October 30 of that year, about the new Random House Unabridged. In it he praises several aspects of the latest entrant in the dictionary market, including the inclusion of several “dirty” words that editors of previous dictionaries had avoided. He confesses that as a child these forbidden words had spurred interest in language, that he “would never have started going through unabridged dictionaries if I hadn’t suspected that there were dirty words hidden in there.”

George Carlin and Kurt Vonnegut were fellow travelers in words.

The second edition of The Random House Unabridged came out in 1987 and my father bought me a copy. Its pages are thinner so as to fit more words in the same space, and it remains on my shelf even though the internet has made it a lonely book, untouched for long periods. And I am happy to report that Mr. Vonnegut made it into the second edition, on page 2,132.

I also have my father’s copy of the first edition, the same one I perused on the living room floor. It shows every bit of its 54 years. The dust jacket disappeared decades ago. The cloth binding is broken and taped at the hinges. The fore-edges of the pages are stained by the touch of many fingers. But it survives and will remain with me until my children have to decide if it’s worth keeping.

As a physical artifact of my childhood, The Random House Unabridged is too full of memories to be abandoned. It is a link to the years before my siblings began to go their separate ways to school, jobs, and marriages, back when playing games or arguing about a trivial point of language might prompt a visit to the shelves to the right of the fireplace. It takes little effort on my part to see it even now, sitting on the floor next to my father’s chair while he worked an acrostic.

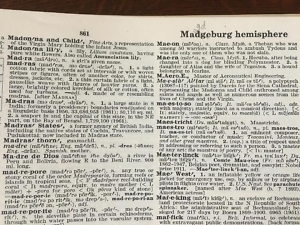

But most haunting is page 861. The last entry on that page is “Magdeburg hemisphere,” a scientific device used to demonstrate the force of air pressure. As in most dictionaries, the first and last entries on each page are printed in the page’s header, and the header on page 861 is the only place any of us ever put a mark in that book. For it is there that my scientist father found a mistake in The Random House Unabridged. In the header, “Magdeburg” is spelled “Madgeburg.” Dad scribbled through the “dg” and carefully penciled in “gd” above it. The letters remain clear, as if he had just written them.

Copyright (c) 2020 by Chris Scott. All rights reserved. A Michigan native, Chris Scott is an unrepentant Yankee who arrived in Nashville more than 30 years ago and has gradually adapted to Southern ways. He is a geologist by profession and a historian by avocation.