To Live on This Margin of Earth

Three debut poetry collections highlight the originality of their authors’ visions

Tara M. Stringfellow’s Magic Enuff

Tara M. Stringfellow’s Magic Enuff foregrounds the intimate experiences of Black Southern girls and women in nuanced, compassionate poems. As these women confront betrayal, loss, and injustice, they offer their strength hand in hand with their vulnerability, and Stringfellow honors it all — “God can stay asleep / these women in my life are magic enuff.”

Stringfellow’s debut novel, Memphis, appeared in 2022. A Memphian herself, Stringfellow sets a number of her poems against a backdrop of the city, imbuing all of them with a rich sense of place, even when setting isn’t an overt element. “Me, Receiving My First Period,” for example, exists in a brief, minimalist space. But its world resonates with the depth and specificity of a short story: “men call it our curse / she says shaking her halo / but it’s not a sin / to bleed for the world.”

Stringfellow’s debut novel, Memphis, appeared in 2022. A Memphian herself, Stringfellow sets a number of her poems against a backdrop of the city, imbuing all of them with a rich sense of place, even when setting isn’t an overt element. “Me, Receiving My First Period,” for example, exists in a brief, minimalist space. But its world resonates with the depth and specificity of a short story: “men call it our curse / she says shaking her halo / but it’s not a sin / to bleed for the world.”

Several poems address the unjust deaths of young Black men that have fed huge waves of public grief and reckoning across the nation in recent years. But in a poem dedicated to Tyre Nichols, victim of a fatal beating by Memphis police officers, the speaker lays out her lifelong experience of such grief, how she “learned to roll my hair with funeral programs,” how “Emmett Till was my Peter Rabbit.” In “For Trayvon’s Mother,” she shares her daily prayer for the survival of her own brother, “same height same build / same fierce fight in him” as Trayvon Martin. “Philando” begins with a stark declaration: “I’d cut off my right / writer’s hand gladly / if I never had to eulogize / another poem for / another Black, dead body.” “To Miss Gianna Floyd” imagines a time of play and beauty for George Floyd’s daughter, even in the shadow of such a heavy legacy.

Stringfellow finishes Magic Enuff with poems that focus on intimate expressions of hope, love, and freedom. “A Black Woman’s Heart” offers a poignant grace note about the speaker’s mother, “a fixer of hearts / a cardiac nurse / every night / during the rounds / she holds them / right in her hands / palms the organs with / the grace, the dignity / of a communion wafer.” When the speaker asks her mother about Black women’s hearts, she answers: “daughter, I don’t know / of a stronger muscle.”

The speaker of “Route to Freedom” voices her deeply rooted sense that true freedom values the choice to stay. Addressing someone she’s dating who tells her that they’ve always got their “exit plan” ready “no matter the girl,” she describes herself as a young child, bags packed and ready to run away from home, poised to jump from her family’s “13th-story / Okinawan penthouse and parachute / down to the earth unscathed.”

But at the precipice, the speaker continues, “perhaps I knew even then / that some things were worth / staying for,” particularly since Black girls have so few “escape hatches” available to them. “[Perhaps] I knew even then / that I had work to do / poems to write / you to meet.” Here, as in all of Magic Enuff, freedom resonates as a rich, emotionally complex experience — hopeful and brave in the face of danger, discerning and intimate in the presence of love.

Magic Enuff

By Tara M. Stringfellow

Dial Press

112 pages

$17

Ben Groner III’s Dust Storms May Exist

“The Window,” the opening poem of Ben Groner III’s debut collection, Dust Storms May Exist, places its speaker at a desk by a window overlooking a bay. From “this rented room in this port city / far from home,” the speaker looks out at the rich night sky, caught up in a moment of arrested attention. “There is a sense my entire life is out / there,” he observes, “verging and pulsing, waiting.” His attention moves then — but not out into the foreign night. He notices the frame of the window itself, then the details of the small rented room around him, the journal in which he has stopped writing.

Suspended between selves, he attunes himself to the ephemeral nature of our identities when we travel. With sensitivity and sharply observed insight, Groner recreates the interior perspective of a roadtripper covering a vast array of terrain, including Virginian frontier life exhibits, New Mexican sand dunes, Argentinian mountains, and more. But when we read these poems, we never lose sight of their true focus: the framing perspective of the traveler’s eye.

Suspended between selves, he attunes himself to the ephemeral nature of our identities when we travel. With sensitivity and sharply observed insight, Groner recreates the interior perspective of a roadtripper covering a vast array of terrain, including Virginian frontier life exhibits, New Mexican sand dunes, Argentinian mountains, and more. But when we read these poems, we never lose sight of their true focus: the framing perspective of the traveler’s eye.

At various points, Groner adds another layer of self-awareness, such as in the collection’s title poem. The speaker eyes a road sign with a peculiar message, “Dust storms may exist”: “I nearly swerved from the blacktop. / Please no, I thought. Not another one. / Not another existential crisis / or metaphysical quandary. / I have enough of those already, plenty / of ghosts flitting across my vision / like tumbleweeds.”

Groner, who currently lives in Nashville, captures both the revelatory thrill and the surreal isolation of the roadtripping observer. Questions arise from chance encounters. Matters of fraught nationhood, climate disaster, and historical upheaval flood into the present moment, as do sudden memories of the speaker’s late father. Traveling provides a unique space where the speaker can exist within these potent subjects, recalling the experience that Joni Mitchell, in her own atmospheric travelogue, Hejira, called “the refuge of the road.”

Such moments also propose a deeper question that every solo traveler knows. Which scene is more real — the vibrant but fleeting one in front of you or the one back home, unfolding now without you?

In a later poem that returns to that same window overlooking a bay far from home, the speaker furthers his sense of dislocation: “To live on this margin of Earth is to be / adrift. Where can one ground oneself?” He considers the life he’s left back home but watches the abundant neighborhood life on the street below him. Stirred by this moment, he vows, “I will join them. I will join them all,” ending the poem with a rich but ambiguous declaration. Joining all means both home and away. But for now, he’s exactly where he was in the first poem: framed at a window, observing life from a distance.

The book’s final poem, “Precarious Cairns,” rests within the tension between the road self and the home self, a tension that is perhaps the greatest strength of this memorable collection: “A few tendrils of knowledge, of truth, / have yet to be pressed into a page, a song. / It has taken me so long to be inside my own life.” Alongside the glorious adventures of the road run the parallel revelations of the traveler’s inner world.

Dust Storms May Exist

By Ben Groner III

Madville Publishing

106 pages

$19.95

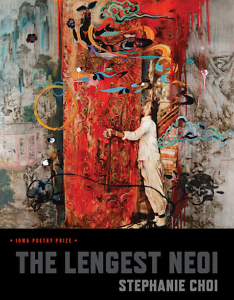

Stephanie Choi’s The Lengest Neoi

Throughout Stephanie Choi’s The Lengest Neoi, names arrive and fall away in layers, reflecting myriad ways to understand the self (or to challenge, unmake, or remake the self) under varying conditions, eras, contexts, and motivations. Choi, who is the current poet-in-residence at Sewanee, The University of the South, won the 2023 Iowa Poetry Prize for this inventive, ambitious debut collection.

We learn the origin of the collection’s title in an early poem, “To Error in Translation.” While traveling in India, the speaker meets a boy from Hong Kong who agrees to translate the Chinese characters of her name for her. “leng neoi is how you write it for someone learning how to speak it, the boy from Hong Kong told me, people would be able to understand. // I make her superlative — the lengest: the tongue writing herself, learning to speak.”

We learn the origin of the collection’s title in an early poem, “To Error in Translation.” While traveling in India, the speaker meets a boy from Hong Kong who agrees to translate the Chinese characters of her name for her. “leng neoi is how you write it for someone learning how to speak it, the boy from Hong Kong told me, people would be able to understand. // I make her superlative — the lengest: the tongue writing herself, learning to speak.”

“The tongue writing herself, learning to speak” — this phrase could describe the thematic core of nearly every poem in the book. Language itself becomes central subject matter and opportunity for innovation. In “Trace Asymmetries,” for example, the speaker recounts extensive dental procedures, including multiple extractions. Choi skillfully removes words, leaving blanks in her speaker’s account of her mother inspecting the state of her mouth, post-extractions.

One poem offers various ways that a voicemail from the speaker’s grandmother could fall prey to mistranslation/transcription/transliteration. Another, titled “A Name That Fell from the Sky,” follows the history of her family’s name before and after a change in spelling and pronunciation during immigration to America. A series of poems, “Emails from Mom,” reveal the anxieties felt by the speaker’s mother, conveyed in warnings and pasted-in links.

In a poem named for the movie Everything, Everywhere, All at Once, the speaker thinks of her grandmother, recognizes the changes wrought by time passing and languages fading from memory: “what’s changed / is how we can speak / to one another, but not / how we love.”

A longer poem, “American | Ghost | Chestnut,” which also uses blanks, explores the American chestnut blight and historical attempts to blame Chinese immigrants for the mass destruction of millions of chestnut trees in the early 20th century. “X-Bred,” which includes a crossword, furthers the imagery of chestnut blight to discuss splits of identity and fraught efforts to restore divided legacies.

These poems, along with numerous others in the collection, mingle strands of language and cultural identity with imagery from nature and the physical life of the body. The speaker’s inherited spinal condition links her to her grandmother and her family lineage (“a face above / crooked body // peering out / to garden of gourds”). Several poems trace the history of the speaker’s tattoos, merging the search for belonging (in both nation and language) with her drive to chronicle her experience.

By the book’s end, The Lengest Neoi has brought its major subjects into full alignment. “A Tattoo for My Mother” overcomes thorny dynamics in lineage, family, and language. We find that she is “undeterred, / outlining my own story — this paper, my skin. My needle — this pen.”

The Lengest Neoi

By Stephanie Choi

University of Iowa Press

102 pages

$22

Emily Choate is the fiction editor of Peauxdunque Review and holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Mississippi Review, storySouth, Shenandoah, The Florida Review, Rappahannock Review, Atticus Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. She lives near Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.