Uncertainty and Possibility

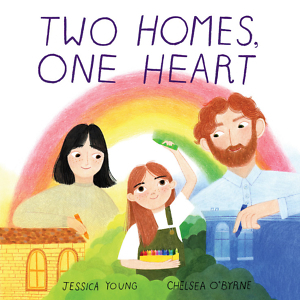

Jessica Young’s Two Homes, One Heart takes on kids’ experience of divorce

Jessica Young has written a wide range of books for children, from board books to adventure series. Her new picture book, Two Homes, One Heart, explores through a child’s eyes the uncertainty and possibility experienced when a family separates: “Two parents, one me. Are we still a family? Whole world turned around. Something lost, something found.”

With lyrical writing, Young balances the loss that accompanies divorce with the hope created by new opportunities: “Two houses, one team. Space to stretch, room to dream.” Accompanying Young’s lyricism, illustrator Chelsea O’Byrne provides lively, warm images that don’t shy away from the tension in separation while revealing the potential for positive change.

With lyrical writing, Young balances the loss that accompanies divorce with the hope created by new opportunities: “Two houses, one team. Space to stretch, room to dream.” Accompanying Young’s lyricism, illustrator Chelsea O’Byrne provides lively, warm images that don’t shy away from the tension in separation while revealing the potential for positive change.

Chapter 16 spoke with Young via email about Two Homes, One Heart and how poetry influences her creative process.

Chapter 16: Two Homes, One Heart captures a child’s perspective on the tension involved in separation or divorce. As the girl in the story considers the separation of her parents, she struggles with the question: Are we still a family? But this unnerving question is gracefully balanced with new possibilities (pets and rooms) that come with separation. When you began writing this story did you intend to balance loss with hopeful possibilities, or did that come later in the process?

Jessica Young: When I started writing, I was trying to distill the experience of spending time in two homes into an essence that readers with a variety of family situations could relate to. I wanted to acknowledge the loss and difficult feelings that can accompany separation or divorce, then find a turning point in the story to discover new possibilities and transition from what’s been lost to what can be gained. After the text was finished, while the illustrations were in process I heard an interview on the radio with Ada Limón reading her poem “Joint Custody,” which beautifully illuminates this idea. I also wanted to explore what “home” is; I feel like we can find homes in places, but also in people, music, art, foods, and books. Some homes are provided for us, and some we create.

Chapter 16: The writing in Two Homes, One Heart is lyrical and resembles a poem. Do you consider yourself a poet? Does poetry shape your writing of children’s books?

Young: I don’t consider myself a poet, but I love poetry. I’m in awe of poets like my friend Charlotte Pence, whose poems are potent and surprising, drawing unexpected connections across subjects and conveying so much with so few words. I think poems, songwriting, and picture books have a lot in common, and I’m often inspired by poetry and music. Whether I’m working on an interactive read-aloud or a lyrical picture book, I love playing with and arranging words.

Young: I don’t consider myself a poet, but I love poetry. I’m in awe of poets like my friend Charlotte Pence, whose poems are potent and surprising, drawing unexpected connections across subjects and conveying so much with so few words. I think poems, songwriting, and picture books have a lot in common, and I’m often inspired by poetry and music. Whether I’m working on an interactive read-aloud or a lyrical picture book, I love playing with and arranging words.

Writing feels almost sculptural to me — adding and subtracting material as a story takes form, trying pieces here and there to see where they fit. Some of my sillier books like the Haggis and Tank Unleashed series, illustrated by James Burks, evolve from experimenting with language (homophones in that case). With lyrical books, I often focus on the sound and flow of words. While I was writing Two Homes, One Heart, I noticed the rhyming phrases created a heartbeat-like cadence, so I tried to work with that rhythmic structure. I introduced pairs of opposite s— hello/goodbye, together/apart, different/same, lost/found, here/there, old/new — to reinforce a feeling of difference or change and add another layer to the text.

Chapter 16: The illustrations are filled with bright, warm colors even on pages intended to show difficult emotions. For a children’s book aimed at a painful topic, this skillful use of color emphasizes the possibility for positive change when life feels turned upside down. Did you ask the illustrator to give attention to this dynamic in the drawings? Or did she pick up on this message on her own?

Young: I love color — my first picture book (My Blue Is Happy, illustrated by Cátia Chien) was inspired by the color blue. So, I was thrilled to see Chelsea O’Byrne’s brilliant palette and her use of color for characterization (the mother is associated with yellow, the father with blue, and the child, green) throughout the story. The saturated hues and layered textures make the illustrations so appealing and accessible. They’re a reminder that there is beauty in difficult times and that creating (a garden, a drawing, a song, a pizza) can be healing.

The colors take me back to my childhood — I can almost smell the crayons! Typically, the author and illustrator don’t have much interaction while working on a picture book (the editor and art director work with each of us as the book develops), but I think it was important to everyone to balance the different aspects of divorce and the feelings associated with it. The seeds of the idea of possibility/positive change were in the text, but Chelsea’s vision and interpretation of them is a great example of how images can transform a story and how picture books are a team sport!

Chapter 16: For several years, I’ve read picture books with my sons, and I’ve noticed illustrations in many books appear stiff and lifeless due to computer programs. The watercolors, colored pencils, and pastels used by O’Byrne offer a refreshing touch. It reminds me of the importance of lively illustrations to bring a story to life. How did you witness O’Byrne’s illustrations bringing your story to life?

Young: I was able to see sketches of the illustrations and was immediately struck by how much emotion they evoked. Spreads like “Two parents, one me. Are we still a family?” where the main character is monumental, sitting in the middle of the image with a home on either side and the gutter (where the pages come together) running right through her, conjure something visually that words can’t express. There’s also so much joy in the illustrations; as I look at the “Space to stretch. Room to dream” pages, I can feel what it’s like to lie in the sun in a grassy field or paint a new room with my favorite color. The characters are so expressive, and I love how the point of view varies, zooming in so we feel like we’re cooking dinner with them then zooming out to show the exteriors of the homes, giving us a glimpse through the windows. It was an incredible gift to see the text brought to life visually in such a beautiful way.

Billy Kilgore is a writer, at-home dad, and ordained pastor. He lives with his wife and two sons in Nashville. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post’s “On Parenting” column, Narratively, Scary Mommy, and Fatherly. He is a graduate of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.