Variations on the Immigrant Life

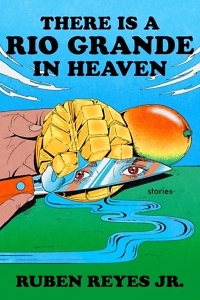

Ruben Reyes Jr.’s debut story collection captures the endless diversity of Latin American migration

The immigrant’s story is impossible to write. A purely fictional account of dislocation and border crossing misses the surreal quality of identity transformation, whereas poetic figuration obscures the gritty reality and practical complexity of the experience. In his debut story collection, There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven, Ruben Reyes Jr. has chosen to solve the problem by scattering the immigrant story across a broad spectrum of literary genres and evoking an expansive range of emotional tones. He employs comedy, tragedy, science fiction, metafiction, and “alternative history” to reflect the irreducible strangeness of transplanting humans from El Salvador to the foreign soils of the United States.

In one of five speculative interludes, each titled “An Alternative History of El Salvador or Perhaps the World,” Reyes offers multiple versions of the afterlife, that final crossing of a Rio Grande that may be “wider than the ocean, wider than a soul” or “barely a creek” or, most likely, “too abstract to describe.” He imagines the trials of death being as multitudinous and profound as those endured by Central Americans in the last half-century. Two characters, Oscar and Valeria, making this ultimate immigration “must cross a million times” and “stare at their reflections and see the million people they are: dry-cheeked Ophelia, humble Icarus, victorious Ahab, undrowned immigrant.”

The collection’s longest story, “Variations on Your Migrant Life,” uses a choose-your-own-adventure conceit to capture the permutations of the immigrant storyline. Reyes thrusts you, a grade-school boy living on a hardscrabble Salvadoran farm, into desperate scenarios and then offers choices on how to proceed. When your Papi tells you that he plans to leave you with Abuelita so that he can join Mami in California, you have two options: “IF YOU BEG HIM TO STAY, GO TO PAGE 166. IF YOU NOD AND TELL HIM YOU’LL MISS HIM, GO TO PAGE 178.”

In this jagged fashion, you join a local gang, or die trying to cross the border into Arizona, or reach your parents in California and redefine yourself as American. Whatever path you choose, you remain aware of the forks that lead to radically different fates, united only by the fact that none of them are easy.

Several of Reyes’ stories address the peculiar problems faced by Salvadoran men who negotiate being gay in a macho subculture. Here again, Reyes creates fantastical premises to explore the conflicts. In “Try Again,” a son spends $10,000 of his father’s life insurance on a SyncALife robot that uses “a chunk of gray matter” from his father’s brain to create a miniaturized AI version of him. He hopes that Dad 2.0 will be more accepting of his sexuality (his original father turned violent when the protagonist told him that he loved a boy), but the robot ends up developing homophobia as virulent as that of the first Dad.

In “Quiero Perrear! and Other Catastrophes,” a young man wakes one day to discover he has been transformed, Kafka-like, into a reggaeton pop star. This Manuel Cisneros, stage name Manu-C, faces a PR crisis: A national tabloid is about to run a story, with photos, claiming he is gay. His handlers have hit on the solution of pairing him with a rising reggaeton singer named Celeste, have them collaborate on music, and fabricate an intimate relationship for the public — everybody wins. The ploy works, for a time, but at the expense of Manuel’s sense of self. In the end, Celeste, facing a parallel dilemma, learns that “the past can be an anchor or a bludgeon, depending on how one wields its weight.”

In “Quiero Perrear! and Other Catastrophes,” a young man wakes one day to discover he has been transformed, Kafka-like, into a reggaeton pop star. This Manuel Cisneros, stage name Manu-C, faces a PR crisis: A national tabloid is about to run a story, with photos, claiming he is gay. His handlers have hit on the solution of pairing him with a rising reggaeton singer named Celeste, have them collaborate on music, and fabricate an intimate relationship for the public — everybody wins. The ploy works, for a time, but at the expense of Manuel’s sense of self. In the end, Celeste, facing a parallel dilemma, learns that “the past can be an anchor or a bludgeon, depending on how one wields its weight.”

Considering this collection’s stunning aesthetic variety, readers are likely to find some stories more compelling than others. In “The Myth of the Self-Made Man,” Reyes jumps forward to the year 2175 in order to look back on the mid-21st century when an immigrant’s son developed a company that inserts “mechanical and electric technologies” into the bodies of 18-year-old humans to turn them into pliant servants. In the climax of the story (a clever example of the George Saunders school of satire), a researcher stumbles on an archive that reveals the horrific extent of the founder’s betrayal of his fellow immigrants.

Reyes’ “alternate histories” extend into the future in “The Salvadoran Slice of Mars,” another story with a sci-fi premise. While richer countries dither about climate change, Central American nations form an alliance to colonize Mars, a prospect that’s especially appealing to populations endangered by rising ocean levels. The point of that story, as with much of this collection, is to highlight the unique plurality of perspectives that emerge from the Central American isthmus. In the Acknowledgments, Reyes thanks “friends and family who’ve shared stories of coming to the United States” and promises, “I’ll keep trying my best to get it right.” With this debut collection, he has made one hell of start.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.