What’s Wrong with Me?

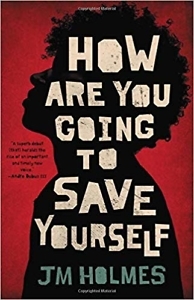

Young men stumble on the path to adulthood in J.M. Holmes’s How Are You Going To Save Yourself

J.M Holmes’s debut story collection, How Are You Going To Save Yourself, appears to be standard fare for the coming-of-age genre. Four high-school friends from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, form a posse in their teens and then drift apart in their twenties. But you won’t find Gio, Rolls, Rye, and Dub hanging out with Holden, Huck, or Ferris Bueller. These stories address twenty-first-century issues, particularly those facing young African-American males, without sugar coating. The result is a book that, while often disturbing, offers authentic accounts of the trials of young adulthood.

In the book’s opening story, “What’s Wrong with You? What’s Wrong with Me?,” the first line provides an accurate preview of the subject matter that follows: “How many white women you been with?” Dub asks Rye. “What’s your number?” Rye responds by arguing that Gio’s own white-women count is immaterial because Gio is mixed race, a racial identity that amounts to “a performance-enhancing drug.”

In the book’s opening story, “What’s Wrong with You? What’s Wrong with Me?,” the first line provides an accurate preview of the subject matter that follows: “How many white women you been with?” Dub asks Rye. “What’s your number?” Rye responds by arguing that Gio’s own white-women count is immaterial because Gio is mixed race, a racial identity that amounts to “a performance-enhancing drug.”

Clearly Holmes is more interested in reality than in discretion. Dub’s friends—including Gio, the narrator of most of the stories-don’t share Dub’s crass attitude, but all voice opinions that are likely to make readers cringe while also nodding in recognition. When Gio catches Rye looking at a picture of Gio’s sexy aunt, Rye defends himself: “She’s got those green eyes,” he says. “I been conditioned.” Holmes’s characters usually don’t bother to rationalize their ethical lapses—their drug use, sexual misconduct, and sporadic violence are part of the waters they swim in.

These stories make it clear that a young man needs a team to escort him into maturity. Left to their own devices, they can fall prey to base instincts and dangerous rebellion. Gio lives with an overworked single mother whose personal resources are maxed out. In “The Legend of Lonnie Lion,” she farms him out to California for a summer with his father, who is sliding downhill fast after a career in the N.F.L. In a later story, a college girlfriend takes on the role of caregiver, exhorting Gio to make his bed. “She liked to smooth and fix and make things neat, molding with her narrow fingers calm and knowing, the look in her eyes soft—let me help build you,” Gio says.

The fathers in these stories are ineffectual ghosts or troublemakers themselves. Gio’s father puts his son on an early flight back east so he can devote all his attention to his drug habit. By the time Gio reaches college, his father has disappeared into the invisible underclass of street addicts. Rolls works in his father’s photography store but receives no guidance from the “gnarled and wiry” man: “His dad thought since he couldn’t hold his own relationships together, he had no place.” Still, Rolls has it better than Rye and Dub, whose fathers are simply absent.

The fathers in these stories are ineffectual ghosts or troublemakers themselves. Gio’s father puts his son on an early flight back east so he can devote all his attention to his drug habit. By the time Gio reaches college, his father has disappeared into the invisible underclass of street addicts. Rolls works in his father’s photography store but receives no guidance from the “gnarled and wiry” man: “His dad thought since he couldn’t hold his own relationships together, he had no place.” Still, Rolls has it better than Rye and Dub, whose fathers are simply absent.

Holmes portrays Pawtucket as no better or worse than any modern American city, with rough neighborhoods bordering middle-class enclaves. For these youths, however, the town represents a rut that they risk falling into. Rye, a superstar athlete in high school, watches his football career get derailed and falls back into a pattern of dealing drugs and getting fired from dead-end jobs. In “Everything is Flammable,” he starts a family and joins the Fire Department, but even then he continues to risk his future by selling narcotics. That story climaxes with Rye in a burning house, its walls on the verge of collapse—a fitting symbol for the situation facing young men who lack the means to escape their doom.

Dub seems marked for a dramatic fall. A hothead who makes no effort to modulate his outbursts, he starts fights for fun, slapping his friends if no stranger is available. When he confronts a Manhattan bouncer, Gio observes that his eyes “went dead like his brain shut off. He wasn’t the de-escalating type.” But instead of self-destructing, Dub descends into schlubby irrelevance, unable to keep his telemarketing job or to hold the interest of his striving girlfriend.

How Are You Going To Save Yourself may challenge readers with its rawness. The sex scenes, including one involving a high-school girl and three older guys in a basement, are intended to shock readers, just as Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero and Nick McDonnell’s Twelve did in decades past. Those disquieting moments are balanced by Holmes’s robust prose, which moves with a distinct rhythm and a lyrical flair. Holmes won’t be writing copy for the New England travel bureau or the Boy Scouts of America—instead, his fiction is that rarest of finds: a fresh voice that tells old stories in an utterly new way.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.