Where the Wild Things Are

In connection with a show at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Mark W. Scala considers the unsettling side of human imagination

“Here there be monsters,” maps once proclaimed in banner notes alongside drawings of giant fish awaiting sailors foolish enough to ignore these helpful warnings. We have always used monsters to speak to ourselves and each other about our deepest fears. They range from the aggressor in Beowulf to that montage of corpses cobbled together by Victor Frankenstein to our current favorites—vampires, zombies, and serial killers. Sometimes monsters can barely be distinguished from angels, as in the hilarious UFO abduction stories that, like go-go boots, had their faddish moment and still occasionally show up at parties.

Meanwhile there are plenty of real monsters to preoccupy our depressed millennial imaginations. Some of the scariest emerge from the human potential to wreak havoc by tinkering with nature, from cloning to genetically modifying crops. If history teaches nothing else, it assures us that we will screw up everything we touch, and nature offers plenty of danger for a reckless fancy ape to play with.

Addressing these urgent issues, but doing so with artful ambiguity rather than with didacticism, is Mark W. Scala’s Fairy Tales, Monsters, and the Genetic Imagination. This beautiful catalog for a current exhibition at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville is both invigorating and disturbing. It’s invigorating because it isn’t another business-as-usual record of a museum playing it safe with crowd-pleasers such as the Impressionists or Andy Warhol, but rather a lively demonstration of a museum engaged with the primordial dark side of the human psyche. It’s disturbing for the same reason, and it’s meant to be.

As Scala remarks in his introductory essay (which bears the same title as the exhibition and book), “If our inner beings are combinations of reason and instinct, traits we often think of as distinguishing human from animal, then fairy tales and other fantastic representations can close gaps within ourselves, and between us and the world.” The many artists represented in this beautiful catalog help us close the gaps by leaping imaginatively across them as if they didn’t exist. Scala argues against notions of human exceptionalism that would prevent such gambols. “For different reasons,” he writes, “dominant veins of theology and science have placed people separate from and above animals, while rejecting fantasy and folklore as expressions of ignorance or childishness.” In reply, fantasy and folklore cavort through this delightful book.

As Scala remarks in his introductory essay (which bears the same title as the exhibition and book), “If our inner beings are combinations of reason and instinct, traits we often think of as distinguishing human from animal, then fairy tales and other fantastic representations can close gaps within ourselves, and between us and the world.” The many artists represented in this beautiful catalog help us close the gaps by leaping imaginatively across them as if they didn’t exist. Scala argues against notions of human exceptionalism that would prevent such gambols. “For different reasons,” he writes, “dominant veins of theology and science have placed people separate from and above animals, while rejecting fantasy and folklore as expressions of ignorance or childishness.” In reply, fantasy and folklore cavort through this delightful book.

Transformation of one creature into another is a key theme throughout. From Ovid’s Metamorphoses to Team Jacob, we have been obsessed with the idea of the fluid essence—one being turning into another, just as alchemists imagined transmuting a baser element into divine gold. Thanks to genetic modification, we are now in the position of alchemists: Soon we will literally transmute the essence of one creature, mixing genes from one into another as calmly as stirring yellow paint into blue to make green. The potential for disastrous consequences in what Scala calls “scientific adventurism,” like nature’s own potential to distort through mutation and deformity, haunts these artists.

The five essays that comprise the text are admirably concise and lucid, addressing both particular works in the catalog and the complex moral and intellectual issues swirling around them. Scala chose the contributing essayists well. They include Suzanne Anker, Marina Warner, Jack Zipes, and Scala himself. The catalog’s only shortcoming is the lack of biographical information about these essayists, but Scala is Chief Curator at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville and author of numerous perceptive scholarly papers and catalog texts, including Gee’s Ben Quilts and the Art of Thornton Dial, which could not possibly differ more from his new book. His writing is admirably free of scholarly dust.

The five essays that comprise the text are admirably concise and lucid, addressing both particular works in the catalog and the complex moral and intellectual issues swirling around them. Scala chose the contributing essayists well. They include Suzanne Anker, Marina Warner, Jack Zipes, and Scala himself. The catalog’s only shortcoming is the lack of biographical information about these essayists, but Scala is Chief Curator at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville and author of numerous perceptive scholarly papers and catalog texts, including Gee’s Ben Quilts and the Art of Thornton Dial, which could not possibly differ more from his new book. His writing is admirably free of scholarly dust.

Suzanne Anker is both artist and critic. As artist she creates grotesquely beautiful and thought-provoking photographs and other artworks that tackle the monsters of contemporary science, while simultaneously performing such unlikely and much-needed tasks as restoring Romantic-era wonder and dread to preserved scientific specimens of the human body. As critic she explores the intersection of science and art in books such as The Molecular Gaze: Art in the Genetic Age. Anker’s essay in this catalog addresses one of the more alarming Frankensteins facing us today and the key concern of the exhibition: “The Extant Vamp (or the) Ire of it All: Fairy Tales and Genetic Engineering.”

Marina Warner is a wonderfully unpredictable writer whose books sparkle with erudition and surprise. She has written poetry, fiction, biography, essays, and apparently everything else, including cultural criticism, such as the fine book known in the U.S. as Monsters of Our Own Making: The Peculiar Pleasure of Fear. Her essay “Metamorphoses of the Monstrous” is the highlight of this book’s text.

Jack Zipes is one of the best-known names in fairy-tale scholarship. He is a formidable scholar and an accessible explicator of our magnetic response to fairy tales and other fictions of the monstrous. Zipes’s essay, “Fairy-Tale Collisions,” examines why most contemporary artists have rejected what he calls “the opulent and extraordinary optimism of the fairy tale” and replaced it with approaches more in tune with a pessimistic view of society and human nature. “Paradoxically,” he writes, “to save the essence of hope in the fairy tale, contemporary visual artists have divested it of beautiful heroes and princesses and cheerful scenes that delude viewers about the meaning of happiness, and at the same time they have endowed the fairy tale with a more profound meaning through the creation of dystopian, grotesque, macabre, and comic configurations.”

Jack Zipes is one of the best-known names in fairy-tale scholarship. He is a formidable scholar and an accessible explicator of our magnetic response to fairy tales and other fictions of the monstrous. Zipes’s essay, “Fairy-Tale Collisions,” examines why most contemporary artists have rejected what he calls “the opulent and extraordinary optimism of the fairy tale” and replaced it with approaches more in tune with a pessimistic view of society and human nature. “Paradoxically,” he writes, “to save the essence of hope in the fairy tale, contemporary visual artists have divested it of beautiful heroes and princesses and cheerful scenes that delude viewers about the meaning of happiness, and at the same time they have endowed the fairy tale with a more profound meaning through the creation of dystopian, grotesque, macabre, and comic configurations.”

Suzanne Anker addresses the same issue: “As stories from oral tradition are retold and codified to produce volumes (as in the work of Hans Christian Andersen or the Brothers Grimm), the Victorian fairy tale moves up the ranks in social class. These volumes form a data bank, like all exemplars of symbolic matrices. Reuse of the extant, so prominent a feature of collage, montage, and appropriation, is a framing device for these collective narratives as well.” And she makes a surprising connection that makes perfect sense and must surely underlie the original urge toward this Frist exhibition: “Within the scientific realm, the readymade has become a resource in xenotransplantation, tissue culturing, and reproductive technologies. While the readymade and its reuse through recontextualization is one of the prime strategies of twentieth-century visual art practice, in the twenty-first century, art and science conceptually share this methodology.”

The word “monster” derives, Marina Warner explains, from the Latin “I show,” but also includes “the memory of the verb moneo, meaning ‘I warn’ or ‘I advise.’” The artists herein could not be busier showing us warnings. Warner writes eloquently of the risk of otherness and bestiality underlying metamorphosis stories. Nebuchadnezzar was cursed to crawl like an animal and eat grass. Gollum hovers between beast and man. Desperately needing anger management, werewolves keep sliding off the human scale and into the animal.

The word “monster” derives, Marina Warner explains, from the Latin “I show,” but also includes “the memory of the verb moneo, meaning ‘I warn’ or ‘I advise.’” The artists herein could not be busier showing us warnings. Warner writes eloquently of the risk of otherness and bestiality underlying metamorphosis stories. Nebuchadnezzar was cursed to crawl like an animal and eat grass. Gollum hovers between beast and man. Desperately needing anger management, werewolves keep sliding off the human scale and into the animal.

Suzanne Anker’s own photographic series “Water Babies,” included in this exhibition, is delightfully ambiguous and allusive. The title plays off the fanciful 1860s serial novel by the Reverend Charles Kingsley, The Water Babies, which was subtitled “A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby.” Kingsley himself was playing with science as much as he was having fun and denouncing child labor. One of the first ecclesiastics to recognize that Darwin’s ideas implied a more contemporary, active creation rather than one static and antique, Kingsley satirized opposition to evolutionary theories within an alternately charming and creepy children’s book. With her usual resonant approach to the icons of science, Anker takes the idea in her own direction, with the “babies” of the title consisting of fetal humans and other animals, and the “water” merely the preserving fluid in which they float.

Naturally an exhibit this diverse demonstrates many such examples of cultural and national cross-fertilization. The American artist Inka Essenhigh, in her 2004 painting Brush with Death, echoes Spaniard Francisco Goya’s series The Disasters of War from the early nineteenth century. Goya’s heartbreaking parade of dozens of prints had already influenced everyone from Géricault to Dalí, and lately has served many artistic purposes for the controversial brothers Dinos and Jake Chapman, who appear in this book with a different series. Essenhigh’s psychic snapshot of evil shows a violent attack by a figure both ghostly and skeletal. As Scala explains, Essenhigh is addressing not only the catastrophic war in Iraq but also her own husband’s involvement in it. She is married to Steve Mumford, a talented artist who has been painting and sketching the front lines in Iraq ever since the war began.

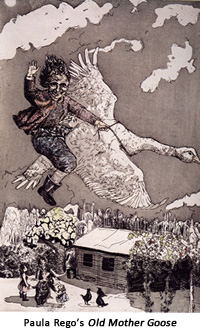

The work of enormously talented contemporary artists fill these lively and satisfying pages. Paula Rego’s lusciously painted and drawn images circle traditional fairy tales and children’s books. Wendy descends from the clouds toward an evil-looking Neverland, while a tiny silhouette of Peter Pan hovers in the sky. Giant insects answer the question “Who Killed Cock Robin?” Little Miss Muffet warily eyes a spider larger than herself, which above its hairy legs has the head of a woman. Kiki Smith, in both a painting and a sculpture, portrays a girl and a woman emerging (triumphantly?) from the body of the slain wolf in Red Riding Hood. David Altmejd’s horrific bust on a sedate museum plinth presents a deformed chicken-headed pseudo-man in a tailored suit, crisp white shirt, and silk tie. He looks like the CEO of Hell.

The work of enormously talented contemporary artists fill these lively and satisfying pages. Paula Rego’s lusciously painted and drawn images circle traditional fairy tales and children’s books. Wendy descends from the clouds toward an evil-looking Neverland, while a tiny silhouette of Peter Pan hovers in the sky. Giant insects answer the question “Who Killed Cock Robin?” Little Miss Muffet warily eyes a spider larger than herself, which above its hairy legs has the head of a woman. Kiki Smith, in both a painting and a sculpture, portrays a girl and a woman emerging (triumphantly?) from the body of the slain wolf in Red Riding Hood. David Altmejd’s horrific bust on a sedate museum plinth presents a deformed chicken-headed pseudo-man in a tailored suit, crisp white shirt, and silk tie. He looks like the CEO of Hell.

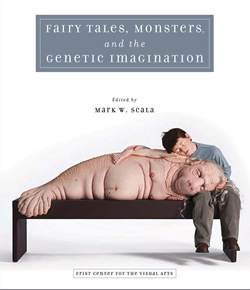

Scala’s exhibition and catalog confront how we turn perennial narratives into new ways of addressing our contemporary fears. It does a beautiful and memorable job. The most resonant and ambiguous image in the book is featured on the cover—Patricia Piccinini’s sculpture The Long Awaited. A young boy sits on a museum bench, tenderly leaning his sleepy head against the fat, outstretched body of a naked creature that seems half walrus (although whiskerless, like a manatee) and half Earth-mother. Its bare navel and nipples contrast with an alarmingly toenailed walrus tail. The boy’s hand is gently entwined in its soft, gray, grandmotherly hair. Viscerally present and unavoidable, a scene tender and bestial, sweet and obscene, it forces the brain to slide from one emotional response to another.

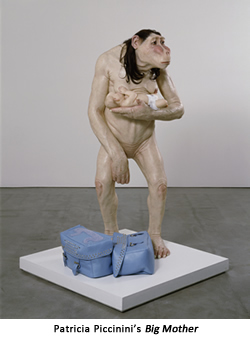

Another Piccinini sculpture nicely represents this book’s wonderful parade of creatures. It’s a haunting figure, a naked but long-haired ape that stands holding a human infant nursing at its breast. The sculpture is slyly allusive, with its head a cross between Picasso’s Baboon and Young—whose own head was famously made from a toy car—and a mandrill’s distinctive display stripes on the long muzzle, here reduced to an incipient wound. The figure seems to be evolving in several directions at once, and it is ready for the journey. At its feet sit two pieces of blue leather luggage.

Michael Sims writes about our imaginative response to nature, in books ranging from Adam’s Navel: A Natural and Cultural History of the Human Form to his recent The Story of Charlotte’s Web, and in essays and articles for The New York Times, New Statesman, Medical Anthropology Quarterly, and many other periodicals.

“Fairy Tales, Monsters, and the Genetic Imagination” runs through May 28 at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts. Click here for exhibition details.